Click here if the embedded video doesn’t work.

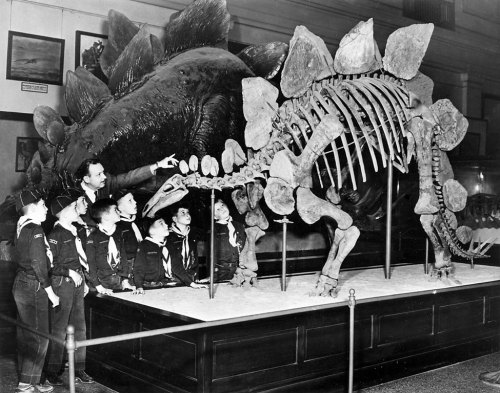

My first love is natural science, but I also fancy myself an amateur art enthusiast, particularly for performance and installation pieces from the last 50 years or so. I am fascinated by art that directly engages the viewer, art that is not complete without the involvement of the spectator. As it happens, mounted fossil skeletons are a great example of installation art, although they are not deliberately constructed as such. The size and presence of a dinosaur skeleton, such as the Stegosaurus below, necessarily incorporates the viewers’ human scale into the experience. Viewers are not merely spectators but participants in a shared performance. Nevertheless, fossils are nearly always displayed and interpreted as scientific specimens, rather than art objects.

Stegosaurus fossil mount and life-size model at USNM circa 1913. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

One important exception occurs in the work of prolific New York-based artist Allan McCollum. McCollum’s installations frequently address repetitive labor and industrial manufacturing, often incorporating hundreds or thousands of similar but subtly unique objects. Each piece is the product of many small actions, gradually assembled over time. In the early 1990s, the artist turned his attention to fossils, particularly their historic meaning and aesthetic appeal.

“Lost Objects” by Allan McCollum. Image from Art21.

In 1991, McCollum collaborated with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History to produce “Lost Objects”, displayed next door at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Using molds taken from dinosaur fossils (apparently all limb bones) in the CMNH collection, the artist produced several hundred fossil casts for the installation shown above. To me, this piece is a reflection on the global sharing of fossil material permitted by casting technology. In the Art21 video at the top of this post, McCollum briefly discusses the prominence of casts among the dinosaur mounts that are a staple at natural history museums. Dinosaur skeletons are virtually never found complete, and mounts are often filled in with casts of specimens held by other museums. For example, the National Museum of Natural History Diplodocus mount incorporates casts of the left hindlimb and much of the neck of the Carnegie Diplodocus. What’s more, casted duplicates of the entire Carnegie Diplodocus can be seen in London, Berlin and several other cities in Europe and Latin America, and casts of the American Museum of Natural History Tyrannosaurus are on display in Denver and Philadelphia. It would be an impressive sight if all the casts of certain fossil specimens scattered around the world were reunited in one room, a monument to the knowledge gained from a century of scholarly collaboration. It would also commemorate the intangible excitement generated by dinosaur mounts, made possible only through the duplication and sharing of casts.

MCollum also comments that “there aren’t as many dinosaur bones in the world as we think.” Perhaps, then, “Lost Objects” is a reflection on the scarcity of intact fossils, by showing an impossibly large collection that no museum could hope to amass. Let’s just hope he wasn’t trying to comment on the alleged mass-production of casts cheapening the original fossils and the museums that hold them, because he’d be dead wrong (EDIT: He wasn’t, see comments).

“Natural Copies” by Allan McCollum. Image from Art21.

In 1995, McCollum followed up on “Lost Objects” with “Natural Copies, a series of casted dinosaur footprints produced in collaboration with the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum. For the artist, this piece was a reflection on the idea that 150 million-year-old fossils can be valued as cultural history. The footprints in question were found by the hundreds in a Utah coal mine. While many ended up at the museum, others were collected by miners to display at home. The fossils took on a second life as symbols the community’s workforce and natural heritage, irrelevant to the dinosaurs that produced the tracks but important all the same. McCollum’s work separates the fossils from their typical scientific context so that viewers may reflect on their cultural meaning and even the aesthetic beauty of their form.

So what’s the point of these installations? These appropriations of fossils as aesthetic pieces has no bearing on the science of paleontology, and in fact may obscure information about how the animals that left these traces lived and behaved. And yet, from the moment a fossil is first seen by human eyes, whether it is an ammonite preserved in a split open rock or the glint of a vertebrate bone weathering out of a hillside, it becomes meaningful on a human scale. For the discoverer, the researcher who describes the fossil, the institution that holds it in its collection and the visitor who sees the fossil on display, that specimen has cultural value. This does not diminish the value of fossils as natural specimens, but rather enhances their importance.

<< Let's just hope he wasn't trying to comment

<< on the alleged mass-production of casts

<< cheapening the original fossils and the

<< museums that hold them, because he'd be

<< dead wrong.

Nope, not my comment! I just like copies a lot, they have their own type of beauty, and the beauty of the rarity of dinosaur bone fossils is enhanced by the beauty of their copies, generated by a worldwide collaboration of natural history museums that transcends politics!