The Hall of Mammals upon its 2003 opening. Photo by John Steiner, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

A century ago, before zoos were widespread and before wildlife videos were a click away, mounting animal pelts on mannequins was the best way to bring nature to an increasingly industrialized populace. Today, taxidermy exhibits seem inherently antiquated, even creepy. Taxidermy is by no means a dead art (competitions are still going strong), but the practice has certainly lost some of its grandeur. For most, the aversion to taxidermy begins and ends with the discomfort of being confronted with a dead animal. There is of course far more complexity to unpack, from the uneasy suspension of disbelief stemming from seeing an animal skin made to look alive to the taxidermy piece’s multifaceted identities (including natural specimen, work of art, historic relic, and so forth). Who was this creature, and how did it die? How did it end up on display? How long has this animal endured its second life? These are the questions that fill visitors’ minds when confronted with a taxidermy exhibits. This presents a challenge for museums seeking to continue to use these specimens to educate visitors about ecology, evolution, and biodiversity. That is the problem staff at the National Museum of Natural History took on when they set out to create a taxidermy hall for a contemporary audience.

Out with the Old

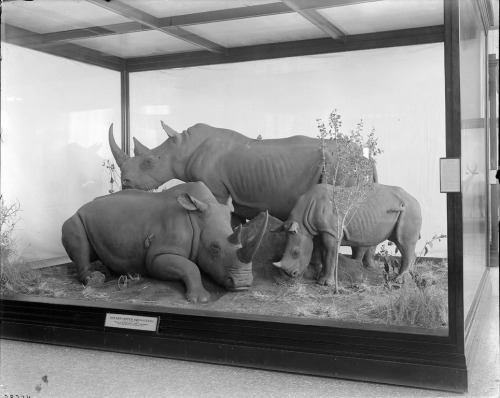

Like any century-old natural history museum, NMNH has a long history of taxidermy displays. Animal mounts filled the original United States National Museum and the Smithsonian’s various world’s fair exhibits. These specimens came from a variety of sources, including private donations and collecting expeditions by Smithsonian researchers. Several animals, such as the hippo mounted by William Brown, lived and eventually died at the National Zoo. Some of the museum’s most famous taxidermy mounts are the animals collected for the Smithsonian by Theodore Roosevelt’s expedition to Uganda, Kenya, and Sudan in 1909. Putting the Roosevelt specimens on display was a priority when the building that is now NMNH opened in 1910. The prepared animals—including a family of lions, a giraffe, three northern white rhinos, and many others—filled an entire room in the new building’s west wing.

Northern white rhinos collected during the Roosevelt expedition, as displayed in 1915. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

In the late 1950s, the NMNH west wing was completely remodeled as part of a Smithsonian-wide modernization project. The wing’s center hall became the Marine Ecosystems exhibit (starring a life-like blue whale model), while the U-shaped corridors surrounding it were rebranded as the World of Mammals Hall and the North American Mammals Hall. In the new exhibits, many specimens were grouped into realistic dioramas, complete with lush foreground landscapes and background murals. Other animals filled more sterile cases dedicated to particular subjects, such as “Mammals versus Climate” and “Dogs of the World.”

African ungulates in the 1959 World of Mammals exhibit. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

By the mid-1990s, the modernized exhibits were looking a little rough around the edges. Many of the taxidermy pieces were over 80 years old, and the fur had become faded or frayed. The exhibit text was wordy and overly technical for the average museumgoer. In 1998, the Smithsonian Institutional Studies Office underwent a detailed evaluation of the mammal exhibits, which involved interviewing hundreds of visitors about their reactions to the halls. Overall, visitors seemed satisfied with the exhibits, but the evaluation nevertheless provided a lot of useful information.

The 1959 exhibits mixed complete dioramas with simpler cases covering specific topics. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Although more than half of museum visitors passed through the mammal exhibits, it was seldom seen as the main attraction. For most visitors, the mammal halls were neither the first exhibit they saw, nor their favorite part of the museum. Older visitors tended to respond better to the mammal exhibits than children or teenagers, who saw the halls as old, boring, or creepy. Indeed, the yuck factor of the taxidermy and the specter of death in general was on many visitors’ minds. While they were often not comfortable talking about it, many visitors expressed concern about the fact that the animals on display were dead, and wondered about how they ended up that way. Out of 750 visitors, 11% were sad or uneasy about the taxidermy and 5% were outright disturbed.

In with the New

In 1997, California real estate developer Kenneth Behring donated $20 million to fund a new mammal hall at NMNH. At the time, this was the largest single donation the museum had ever received, and it presented an exciting opportunity. However, there was a conflict of interest: Behring was a big game hunter with a history of going after threatened species. For example, earlier that year Behring drew criticism from the Humane Society after killing a Kara-Tau argali (an endangered mountain sheep) in Kazakhstan. In a news release, Behring stated that he followed all applicable laws and always obtained proper permits, but many individuals—both within and outside the Smithsonian—were concerned that his hunting activities conflicted with the museum’s conservation-oriented mission. What’s more, Behring’s donation included 22 animals from his own collection, and the Smithsonian was accused of allowing him to buy his way into the institution’s prestigious exhibits.

While the Kenneth E. Behring Family Hall of Mammals bears the donor’s name, and several of his personal trophies are on display, NMNH staff have made it very clear that Behring had no say in the exhibit’s message or content. That was just as well, because developing the exhibit internally proved plenty difficult. Pencils were allegedly thrown during meetings, and one conservator chose to retire rather than work on the new hall.

Several individuals can rightly claim authorship of the Hall of Mammals, including Project Manager Sally Love and Writer Sharon Barry. However, the primary advocate for the hall’s striking and controversial design was Associate Director of Exhibits Robert “Sully” Sullivan. Sullivan envisioned a wide open hall, forgoing enclosed dioramas and instead displaying animals in simple settings with lots of negative space. The idea was to keep the focus on the animals, their anatomy, and their behavior. This steel-and-glass, contemporary aesthetic had more in common with trendy tech showrooms than traditional taxidermy displays, and not everyone was initially on board.

This Alaskan moose group was one of several dioramas dismantled to make way for the new Hall of Mammals. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Unfortunately, the bold new vision could not be accomplished without destroying the old exhibits, including the historic dioramas. In the early 20th century, the proliferation of habitat dioramas radically transformed museums. Dioramas were accessible to broad audiences and brought with them the idea that museum exhibits should tell stories. These exhibits even had a tangible effect on the increasingly urban public’s interest in conservation. Today, historic museum dioramas are often considered quaint, but in their day they represented a bold fusion of art, technology, and science.

According to Lawrence Heaney of the Field Museum of Natural History, the NMNH dioramas “were not particularly good.” Still, they were important historical artifacts and represented a huge amount of work on the part of the craftspeople who created them. After inspecting the exhibits, NMNH conservators reported that it would be possible to preserve the dioramas intact for some future use. However, top officials decided that this would be too expensive, and all of the dioramas were ultimately demolished. Some of the taxidermy mounts were cleaned up for the new exhibit, while others were passed on to other museums. Still others would up homeless, and were ultimately dismantled and harvested for parts.

While some traditionalists fretted about Sullivan’s push to eliminate the dioramas, he also made waves with his restructuring of the exhibit team. In the past, curators had primary authorship over exhibit content, but Sullivan wanted to democratize the process. He gave designers and educators a greater voice, and insisted that their specialized knowledge be heard. While many applauded the recognition Sullivan brought to professionals whose work was usually undervalued, others weren’t so sure. Research staff avoided exhibit work during Sullivan’s tenure because they felt they were being railroaded into plans that had already been made. It was a tense period, and for a time, there were no curators on the Hall of Mammals team. Fortunately, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Anna K. Behrensmeyer and senior mammal specialist (and former NMNH director) Robert Hoffman eventually stepped up as advisers for the project. They brought to the table a phylogenetic approach that enhanced the strictly regional layout that had been planned for the exhibit.

Phylogeny became a key theme once Behrensmeyer and Hoffman joined the exhibit team. Photo by the author.

Yet another challenge emerged when the architectural firm NMNH hired to collaborate on the design restructured their staff midway through the project. No longer getting the results they wanted, NMNH hired a new firm—Reich+Petch Design International—to finish the job, at the cost of a multi-month delay. The new exhibit architects determined that the first draft simply had too much content. If all the planned displays were included, the Hall of Mammals would be very crowded and visitor traffic flow would be encumbered. The team confirmed this by laying out a mock-up of the floor plan on the National Mall. After walking through the space, the exhibit team decided to cut about 40% of the content and tighten up the interpretive themes. The hall’s final design is all about evolution, and our own place in the mammal family tree.

With a plan in place, construction and fabrication were set to begin. We’ll cover that in the next post. Stay tuned!

References

Institutional Studies Office. 1999. Examining Mammals: Three Studies of Visitor Responses to the Mammals Hall in the National Museum of Natural history. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Marsh, D.E. 2014. From Extinct Monsters to Deep Time: An ethnography of fossil exhibits production at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. http://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/50177

Milgrom, M. 2010. Still Life: Adventures in Taxidermy. New York, NY: Mariner Books.

National Park Service. 2004. Mammal Hall Study Report: Evaluation by National Park Service Media Specialists of New Exhibits at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Dc. https://www.nps.gov/hfc/pdf/imi/si-mammal-hall-report.pdf

Parrish, M. and Griswold, B. 2004. March 2004 Meeting Report: Mammals on Parade. Guild of Natural Science Illustrators. http://www.gnsi.science-art.com/GNSIDC/reports/2004Mar/mar2004.html

Trescott, J. 2003. Look Alive! The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/2003/07/14/look-alive/d1944407-ffbb-4e1f-8e06-06cd9ddec57d

Ulaby, N. 2010. Smithsonian Taxidermist: A Dying Job Title. All Things Considered, National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=125914878