About a year ago, I wrote this post about the dinosaurs of the London Natural History Museum, admittedly in a bit of a hurry. The post has proven very popular, which leads me to conclude there’s interest in more “quick bite” articles about the specimens on display at various museums. I’ll see about putting together more of these in the future.

For now, I’ll start close to home, with the dinosaurs on display at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH). This entry is about the most notable specimens that were acquired outside the living memory of current staff. I’ll follow up with an article about more recent acquisitions sometime soon. It’s important to note that while I’m focusing on dinosaurs here, the real meat of the Field Museum’s vertebrate paleontology collection is in its Cenozoic holdings. Those too will need to be a topic for another time.

Brachiosaurus altithorax (P 25107)

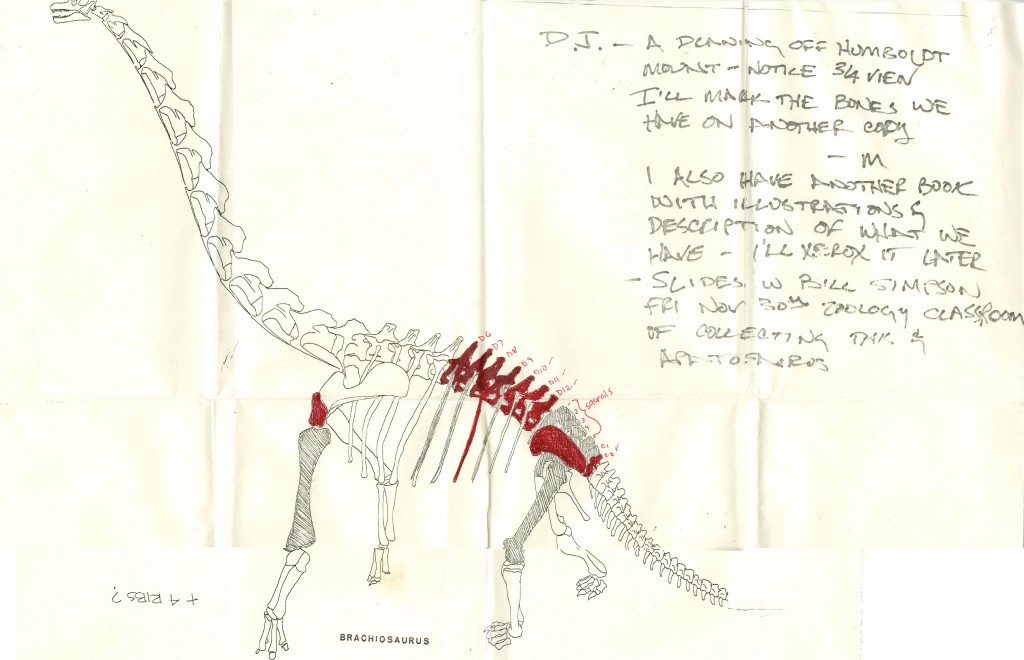

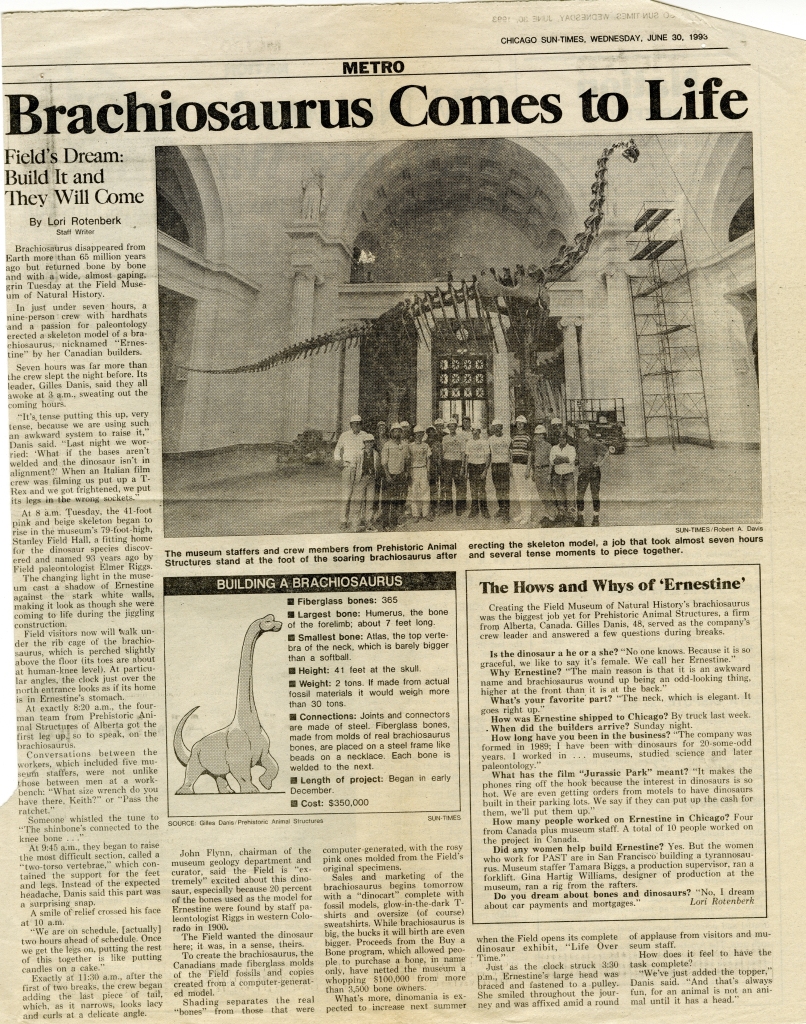

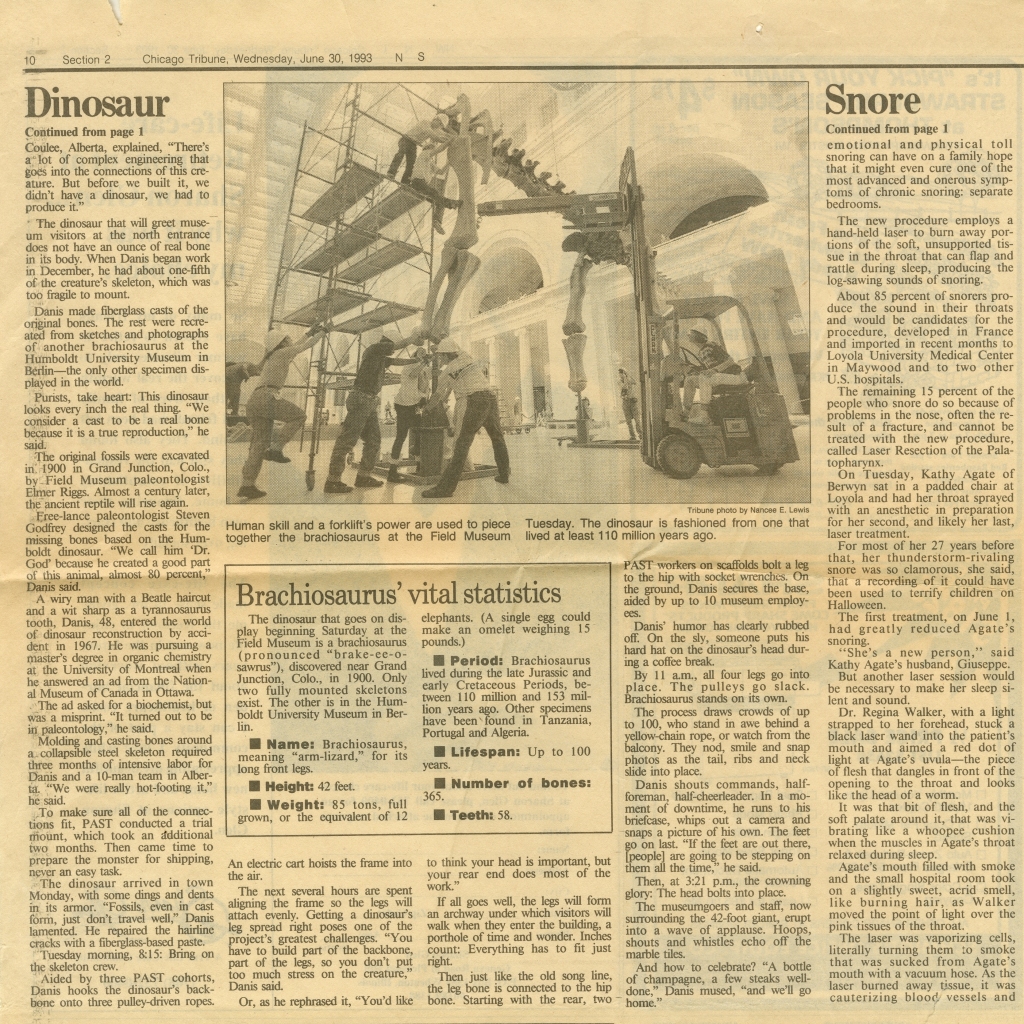

The first dinosaur discovered by Field Museum paleontologists was nothing less than the biggest land animal known at the time. On July 4, 1900, the museum’s first paleontologist Elmer Riggs and his assistant H.W. Menke came upon a set of enormous bones in western Colorado. Riggs—who was specifically hired two years earlier to find dinosaurs for the nascent museum—named the new dinosaur Brachiosaurus altithorax in 1903. The individual bones were set in display cabinets (left image, below) around the same time. Comprising about 25% of the skeleton, Riggs did not consider the find complete enough to assemble into a standing mount. Nevertheless, the museum commissioned a replica Brachiosaurus skeleton about 90 years later, basing the missing pieces on the related Giraffatitan.

New Brachiosaurus fossils have proven elusive. While several individual bones have been found, the holotype collected by Riggs and Menke remains the most complete example of this famous dinosaur.

“Apatosaurus” sp. (P 25112 and P 27021)

Riggs and Menke found another sauropod in western Colorado in 1900, and returned the following year to excavate it. This time, they had the back two-thirds of an apatosaurine sauropod, complete save for the distal portions of the limbs and tail. As museum leaders were unwilling to fund a search for more sauropod material, Riggs mounted the partial skeleton in 1908 (left image, above).

The sauropod remained in this unfinished state until the 1950s, when preparator Orville Gilpin arranged to acquire another incomplete sauropod. Gilpin had excavated the specimen with Jim Quinn near Moab, Utah in 1941, and knew that it was a perfect complement to the skeleton on display. Long-time museum president Stanley Field (nephew of founder Marshall Field) had repeatedly resisted requests from the paleontology staff to complete the mount, but allegedly relented after overhearing a visitor ask which side of the half-dinosaur was the front. Gilpin built an armature for the neck and shoulders of the newly acquired specimen (right image, above), and finished the mount with casts of Apatosaurus forelimbs and a Camarasaurus skull from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The Field Museum finally had a complete sauropod on display, which was unveiled at the April 1958 Members’ Night.

In 1992, the composite sauropod was dismantled and relocated to the new Life Over Time exhibition on the other side of the building. The museum hired Prehistoric Animal Structures, Inc.—a now-shuttered company specializing in mounting fossil skeletons—to do the work. The updated sauropod debuted in 1994, now posed as though looking at visitors on a nearby elevated walkway. The sauropod remained in place when Life Over Time became Evolving Planet in 2006, though with the walkway gone it now appears to be admiring the Charles Knight murals on the wall.

A note on nomenclature: Riggs identified this skeleton as Apatosaurus, but the label was changed to Brontosaurus in the mid-20th century, when Apatosaurus fell out of common parlance. The name Apatosaurus returned to labels in 1994. However the most recent word on this specimen—from Tschopp et. al 2015—is that it’s not Apatosaurus nor Brontosaurus, but likely another, yet unnamed taxon.

Triceratops horridus (P 12003)

In 1904, Riggs moved on from the Jurassic-aged rocks of Colorado to the Cretaceous of Carter County, Montana. Today, this part of southeast Montana is lousy with paleontologists. There’s even an annual shindig for field crews held at the Carter County Museum in Ekalaka. However, Riggs’ expedition was among the first to visit the region from a large museum. The most significant find of the summer was a Triceratops skull and partial skeleton from just west of the Chalk Buttes.

The skull was prepared by 1905 and has been in every iteration of the Field Museum’s paleontology halls. The unusually thick brow horns were recently confirmed to be real bone, but it’s possible that they were originally from another, larger specimen (edit: There is real bone inside the horns, but they are padded with a lot of plaster reconstruction—see comments). The remainder of the skeleton remains in storage.

Gorgosaurus libratus (PR 2211)

Most collecting was paused during World War I, but shortly after the war, Marshall Field III funded new expeditions in all four of the Field Museum’s major research areas (Zoology, Botany, Geology, and Anthropology). Riggs led three of these expeditions, one to Alberta and two to Argentina and Bolivia. Riggs saw the 1922 Alberta trip as something of a practice run, since he hadn’t been in the field in years, and some on his team had never done fieldwork at all.

Still, the crew was serious about bringing in fossils. Riggs decided to go to the Red Deer River region of Alberta, a place where his former colleague and classmate Barnum Brown had unearthed numerous near-complete dinosaurs for the American Museum of Natural History. Riggs also hired fossil hunter George F. Sternberg, who already knew the area well, to join him on the 14-week expedition.

After returning from Alberta, Riggs was busy getting ready for the upcoming expeditions to South America, and most of the field jackets remained unopened for years, or even decades. One jacket lingered until 1999, when the large team of preparators assembled to prep SUE the T. rex decided to crack it open.

Inside, they found the virtually complete hips, hindlimbs, and tail of a four-year-old Gorgosaurus, which they named Elmer. Riggs’ notes indicated that the skull ought to have been present, but the preparators only found a few teeth. Further investigation revealed that the partial skull had been in its own jacket with a different number, and that it had been loaned to the University of California at Berkeley in the 1970s. The Berkeley scientists had subsequently lost the fossil, but (fortunately) made a cast of it, which was later returned to the Field Museum.

Elmer was included in the touring exhibition Dinosaurs: Ancient Fossils, New Discoveries, and most recently in 2017’s Specimens: Unlocking the Secrets of Life. It is currently off exhibit.

Lambeosaurus lambei (PR 380)

According to Riggs, the “prize find” of the 1922 Alberta expedition was a Lambeosaurus found by Sternberg. Even in the field, it was clear that the skeleton was completely intact, save for the head, part of the neck, and the tip of the tail. Sternberg’s field notes indicate that the weathered side included a number of large skin impressions. The Lambeosaurus was jacketed and excavated in eight sections, totaling about three tons of rock and fossil.

Like Elmer the Gorgosaurus, the Lambeosaurus was left unprepared while Field Museum preparators focused on the fossils from South America. In 1947, the University of Chicago closed its geology museum and donated its collections to the Field Museum, pushing the Alberta fossils even further down the queue. Stanley Kuczek finally prepared the Lambeosaurus in 1954, when it was slated to be paired with Daspletosaurus in a new display (more below).

Kuczek prepared only the unweathered (face-down in the field) side of the skeleton, so the skin impressions Sternberg reported are still embedded in the matrix under the fossil. A Lambeosaurus skull from the University of Chicago collection (UC 1479) was used to complete the display. Sternberg’s Lambeosaurus remains the most complete non-bird dinosaur at the Field Museum, and a (perhaps unsung) highlight of the collection.

Daspletosaurus torosus (PR 308)

The Field Museum’s Daspletosaurus, sometimes called “Gorgeous George,” was collected by Barnum Brown of the American Museum of Natural History in 1914. It came from the same region of Alberta that Riggs and company would visit eight years later. At the time, the partial skeleton was considered an example of Gorgosaurus, of which the New York museum already had three. In 1955, Field Museum board member Louis Ware offered to buy the American Museum’s spare tyrannosaur, and soon the fossil was on its way to Chicago.

Orville Gilpin mounted the skeleton—which has been known as Daspletosaurus since 1999—for display. He elected to create a completely free-standing mount, with no visible armature. This required drilling through each of the vertebrae to thread a steel pipe through, as well as splitting the right femur. These destructive practices would never be undertaken today, but in the mid 20th century, dinosaurs were seen as display pieces first and scientific specimens second.

Like the “Apatosaurus,” Gorgeous George was revealed to the public during Members’ Night. The skeleton was placed at the south end of the museum’s central Stanley Field Hall, standing over Sternberg’s Lambeosaurus as though it had just brought down the herbivore. In 1992, Prehistoric Animal Structures, Inc. remounted the Daspletosaurus in a more accurate horizontal posture, once again poised over its Lambeosaurus prey. The real skull has never been mounted on the skeleton, but it is currently on display near the museum’s east entrance.

Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus (P 27393)

The Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus holotype was found by Charles Sternberg (father of George) in 1923, near Fruitland, New Mexico. It made it to the Field Museum through a series of exchanges, but was not prepared until the 1950s. John Ostrom published a description of the skeleton and partial skull in 1961, noting that it was nearly identical to Parasaurolophus walkeri from Alberta, except for the crest on the back of its head. While P. walkeri has a long, backward-projecting crest, the New Mexico species has a short crest that curves downward.

The Parasaurolophus was first exhibited in 1994, as part of Life Over Time. The 70% complete skeleton was mounted directly to a wall, with illustrations of the missing bones behind it. Ten years later, Research Casting International was brought in to turn the Parasaurolophus into a complete standing mount. Like most modern mounts, the armature is designed so that each bone can be removed individually for study or conservation. Captured in a graceful walking pose, the Parasaurolophus is—in my opinion—the most elegant and evocative dinosaur mount at the Field Museum.

References

Brinkman, P. 2000. Establishing vertebrate paleontology at Chicago’s Field Columbian Museum, 1893–1898. Archives of Natural History 27:81–114.

Brinkman, P. 2010. The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush: Museums and Paleontology in America at the Turn of the 20th Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brinkman, P. 2013. Red Deer River shakedown: a history of the Captain Marshall Field paleontological expedition to Alberta, 1922, and its aftermath. Earth Sciences History 32:2:204-234.

Erickson, G.M, Makovicky, P.J., Currie, P.J., Norell, M.A., Yerby, S.A., and Brochu, C.A. 2004. Gigantism and life history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs. Nature 430:722–775.

Forster, C.A. 1996. Species resolution in Triceratops: cladistic and morphometric approaches. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16:2:259–270.

Gilpin, O. 1959. A free-standing mount of Gorgosaurus. Curator: The Museum Journal 2:2:162–168.

Ostrom, J.H. 1961. A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of New Mexico. Journal of Paleontology 35:3:575–577.