Note: This post was written in 2014. It predates Emanuel Tschopp and colleagues’ landmark paper which, among other things, resurrected the genus Brontosaurus. I’ve attempted to update the taxonomy where appropriate, but it may still be a bit of a mess.

The story of the mismatched head of Brontosaurus is one of the best known tales from the history of paleontology. I think I first heard it while watching my tattered VHS copy of More Dinosaurs—scientists had mistakenly mounted the skull of Camarasaurus on an Apatosaurus skeleton, and the error went unnoticed for decades. The legend has been repeated countless times, perhaps because we revel in the idea that even experts can make silly mistakes. Nevertheless, I think it’s time we set the record straight: nobody ever mistakenly placed a Camarasaurus skull on Apatosaurus. The truth is a lot more nuanced—and a lot more interesting—than a simple case of mistaken identity.

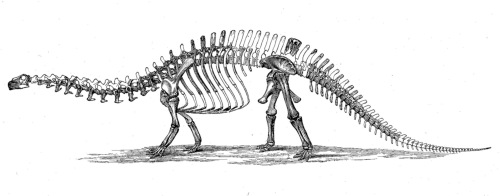

Intrinsically related to the head-swap story is the replacement of “Brontosaurus” with “Apatosaurus” in the popular lexicon. This is well covered elsewhere, so I’ll be brief. Scientific names for animals are governed by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, which includes the principle of priority: if an organism has been given more than one name, the oldest published name is the correct one. Leading 19th century paleontologist O.C. Marsh named Apatosaurus ajax in 1877, based on a vertebral column discovered in the Morrison Formation of Colorado. Two years later, Marsh introduced Brontosaurus excelsus to the world, from a more complete specimen uncovered in rocks of the same age in Wyoming. Like many of Marsh’s publications, these descriptions were extremely brief, offering a scant two paragraphs for each taxon. However, Marsh did provide a longer description of Brontosaurus in 1883, complete with the first-ever restoration of the complete skeleton.

Come play with us, Brontosaurus…forever and ever and ever. Photo courtesy of the AMNH Research Library.

In 1903, Elmer Riggs of the Field Museum of Natural History underwent a survey of sauropod fossils held at various museums and concluded that Brontosaurus excelsus was too similar to Apatosaurus to merit its own genus. The name “Brontosaurus” was dropped, and the species became Apatosaurus excelsus for most of the 20th century. However, a substantial re-evaluation of diplodocoid sauropods by Emanuel Tschopp and colleagues in 2015 reversed Riggs’ decision. So the name Brontosaurus is back, but keep in mind that the species excelsus never actually went anywhere—it was just hidden under the Apatosaurus umbrella. Following Tschopp et al., Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus were distinct animals that lived in the same environment.

So how does the mismatched head fit into all of this? The short answer is that it doesn’t. The fact that some Apatosaurus mounts had incorrect heads for much of the 20th century has nothing to do with which name was being used at any given time, although the two issues have often been conflated in popular books. I suspect the two stories got mixed up because paleontologists were pushing to correct both misconceptions around the same time during the dinosaur renaissance.

Let’s go back to Marsh’s 1891 Brontosaurus reconstruction*, pictured above. The Brontosaurus type specimen did not include a head, and many have reported that Marsh used a Camarasaurus skull in this illustration. However, this would not have been possible, because the first complete Camarasaurus skull wasn’t discovered until 1899. What Marsh had instead was a few fragmentary bits of Camarasaurus cranial material, plus a snout and jaw (USNM 5730) now thought to be Brachiosaurus (more on this at SV-POW). Although these pieces were found far from the Brontosaurus quarry, Marsh extrapolated from them to create the best-guess skull that appears in his published reconstruction.

*Note that this is the second of two Brontosaurus reconstructions commissioned by Marsh. The first drawing, published in 1883, has somewhat different skull, but it still does not resemble Camarasaurus.

Although Stephen Gould states in his classic essay “Bully for Brontosaurus” that Marsh mounted the Brontosaurus holotype at the Yale Peabody Museum, Marsh never saw his most famous dinosaur assembled in three dimensions. In fact, Marsh strongly disliked the idea of mounting fossil skeletons, considering it a trivial endeavor of no benefit to science. Instead, it was Adam Hermann of the American Museum of Natural History, supervised by Henry Osborn, who built the original Brontosaurus/Apatosaurus mount (AMNH 460), six years after Marsh’s death in 1899.

Clockwise from top: AMNH sculpted skull (Source), Peabody Museum sculpted skull, real Apatosaurus skull (Source), and real Camarasaurus skull.

To create the mounted skeleton, Hermann combined fossil material from four separate individuals. All of the material had been collected by AMNH teams in Wyoming specifically for a display mount—and to beat Andrew Carnegie at building the first mounted sauropod. Like Marsh, however, they failed to find an associated skull (a Camarasaurus-like tooth was allegedly found near the primary specimen, but it has since been lost). Even today, sauropod skulls are notoriously rare, perhaps because they are quick to fall off and roll away during decomposition. Instead, Hermann was forced to make a stand-in skull in plaster. Osborn explained in an associated publication that this model skull was “largely conjectural and based on that of Morosaurus” (Morosaurus was a competing name for Camarasaurus that is no longer used).

Was it really, though? The sculpted skull is charmingly crude, so the overt differences between the model and a real Camarasaurus skull (top and bottom left in the image above) might be attributed to the simplicity of the model. Note that there isn’t even an open space between the upper and lower jaws! Still, Hermann’s model bears a striking resemblance to Marsh’s illustration in certain details, principally the elongate snout and the very large, ovoid orbit. It’s reasonable to assume that Hermann used Marsh’s speculative drawing as a reference, in addition to any actual Camarasaurus material that was available to him. At the very least, it is incorrect to say that AMNH staff mistakenly gave the mount a Camarasaurus skull, since Osborn openly states that it is a “conjectural” model.

A young Mark Norell leads the removal of the sculpted skull from the classic AMNH Apatosaurus. Source

In 1909, a team led by Earl Douglass of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History finally discovered a real Apatosaurus skull (third image, lower right). They were working at the eastern Utah quarry that is now Dinosaur National Monument, excavating the most complete Apatosaurus skeleton yet found (CM 3018). The skull in question (cataloged as CM 11162) was not connected to the skeleton, but Douglass had little doubt that they belonged together. Back at the Carnegie Museum, director William Holland all but confirmed this when he found that the skull fit neatly with the skeleton’s first cervical vertebra. As he wrote at the time, “this confirms…that Marsh’s Brontosaurus skull is a myth.”

The Carnegie team prepared and mounted the new Apatosaurus, and Holland initially planned to use the associated skull. However, when Osborn heard about this he threatened to ruin Holland’s career if he went through with it. You see, the new skull looked nothing like the round, pseudo-Camarasaurus model skull on the AMNH mount. Instead, it was flat and broad, like a more robust version of Diplodocus. Osborn wasn’t about to let Holland contradict his museum’s star attraction, and Holland backed down, never completing his planned publication on the true nature of Apatosaurus. Meanwhile, the mounted skeleton at the Carnegie Museum remained headless until Holland’s death in 1932. After that, museum staff quietly added a Camarasaurus-like skull. This was an important event, as it would be the first time an actual cast skull of Camarasaurus (as opposed to a freehand sculpture) would be attached to a mounted Apatosaurus skeleton. While I’ve had no luck determining precisely who was involved, Keith Parsons speculated that the decision was made primarily for aesthetic reasons.

Carnegie Museum Apatosaurus alongside the famed Diplodocus, sometime after 1934. Source

Elmer Riggs assembled a third Apatosaurus mount (FMNH P 25112) at the Field Museum in 1908. Riggs had recovered the articulated and nearly complete back end of the sauropod near Fruita, Colorado in 1901, but was unable to secure funding for further collecting trips to complete the mount. Riggs was forced to mount his half Apatosaurus as-is, and the absurd display stood teetering on its back legs for 50 years. Finally, Riggs’ successor Orville Gilpin acquired enough Apatosaurus fossils to complete the mount in 1958. As usual, no head was available, so Gilpin followed the Carnegie Museum’s lead and gave the mount a cast Camarasaurus skull.

The last classic apatosaurine mount was built at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History in 1931, using Marsh’s original Brontosaurus excelsus holotype (YPM 1980) and a lot of plaster padding. The skull this mount originally sported (third image, upper right) is undoubtedly the strangest of the lot. A plaster replica sculpted around a small portion of a real Camarasaurus mandible, this model doesn’t look like any known sauropod. The overall shape is much more elongated than either Camarasaurus or the AMNH model, and may have been inspired by Marsh’s hypothetical illustration. Other details, however, are completely new. The anteorbital fenestrae are thin horizontal slashes, rather than the wide openings in previous reconstructions, while the tiny, forward-leaning nares don’t look like any dinosaur skull—real or imaginary—I’ve ever seen. The sculptor is sadly unknown, but this model almost looks like a committee-assembled combination of the Marsh drawing, the AMNH model, and CM 11162 (a.k.a. the real Apatosaurus skull).

During the mid-20th century, vertebrate paleontology lapsed into a quiet period. Although the aging dinosaur displays at American museums remained popular with the public, these animals came to be perceived as evolutionary dead-ends, of little interest to the majority of scientists. The controversies surrounding old mounts were largely forgotten, even among specialists, and museum visitors saw no reason not to accept these reconstructions (museums are, after all, one of the most trusted sources of information around).

The Peabody Brontosaurus with its original head. Note that the Camarasaurus in the foreground also has a sculpted skull.

This changed with the onset of the dinosaur renaissance in the 1970s and 80s, which brought renewed energy to the discipline in the wake of new evidence that dinosaurs had been energetic and socially sophisticated animals. In the midst of this revolution, John McIntosh of Wesleyan University re-identified the real skull of Apatosaurus. Along with David Berman, McIntosh studied the archived notes of Marsh, Douglass, and Holland and tracked down the various specimens on which reconstructed skulls had been based. They determined that Marsh’s restoration of the Brontosaurus skull, long accepted as dogma, had in fact been almost entirely arbitrary. Following the trail of guesswork, misunderstandings, and scientific inertia, McIntosh and Berman proved that Holland had been right all along. The skull recovered at Dinosaur National Monument along with the Carnegie Apatosaurus was in fact the only legitimate skull ever found from an apatosaurine up to that point. In 1981, McIntosh himself replaced the head of the Peabody Museum Brontosaurus with a cast of the Carnegie skull. AMNH, the Field Museum, and the Carnegie Museum followed suit before the decade was out.

Given the small size of the historic community of dinosaur specialists, it may have been particularly vulnerable to the influences of a few charismatic individuals. To wit, Marsh’s speculative Brontosaurus skull was widely accepted despite a lack of compelling evidence, and Osborn was apparently able to bully Holland out of publishing a find that contradicted the mount at AMNH. What’s more, the legend of the mismatched Brontosaurus skull somehow became distorted by the idea that either Marsh or Osborn had accidentally given their reconstructions the head of Camarasaurus. This is marginally true at best, since both men actually oversaw the creation of composite reconstructions which only passingly resembled Camarasaurus. Nevertheless, the idea that the skull of Camarasaurus was a passable substitute for that of Apatosaurus was apparently well-established by the 1930s, when Carnegie staff hybridized the two sauropods for the first time. Even today, there are numerous conflicting versions of this story, and it is difficult to sort out which details are historically accurate and which are merely assumed.

I’d like to close by pointing out that while the head-swap story is often recounted as a scientific gaffe, it is really an example of science working as it should. Although it took a few decades, the mistakes of the past were overcome by sound evidence. Despite powerful social and political influences, evidence and reason eventually won out, demonstrating the self-corrective power of the scientific process.

References

Berman, D.S. and McIntosh, J.S. 1975. Description of the Palate and Lower Jaw of the Sauropod Dinosaur Diplodocus with Remarks on the Nature of the Skull of Apatosaurus. Journal of Paleontology 49:1:187-199.

Brinkman, P. 2006. Bully for Apatosaurus. Endeavour 30:4:126-130.

Gould, S.J. 1991. Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company.

Osborn, H.F. 1905. Skull and Skeleton of the Sauropodous Dinosaurs, Morosaurus and Brontosaurus. Science 22:560:374-376.

Parsons, K.M. 1997. The Wrongheaded Dinosaur. Carnegie Magazine. November/December:38.

2015. A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda). PeerJ 3:e857. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.857

Pingback: How did the horrible Yale “Brontosaurus” skull come to be? | Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week

Re: Holland being “bullied” by HF Osborn: an excerpt from Keith Parsons’ essay on The Wrongheaded Dinosaur:

“Why didn’t Holland attach a cast of CM 11162 if he thought it was the right one? Some have suggested that Holland wanted to avoid conflict with Henry Fairfield Osborn, head of the American Museum of Natural History, who had dared Holland to mount the Diplodocus-like skull.

“Holland, though, was not afraid of controversy. On the contrary, he was a skilled polemicist who could devastate opponents with a combination of biting sarcasm and airtight logic.

“A more likely explanation is that Earl Douglass continued to make spectacular discoveries at Carnegie Quarry, and as long as Douglass’ excavations continued, there was a chance that he would find an Apatosaurus neck with the skull attached.”

For an example of Holland being combative, see his treatment of the sprawling Diplodocus of Hay and others. I’m inclined to agree with Parsons that Holland was being cautious, rather than being intimidated by HFO!

Tom Johnson

Reblogged this on Shinrin Art Blog.

And now it’s just getting more weird as I read some new research says there may be both an Apatosaurus and a Brontosaurus. Something about how the finer details being overlooked for nearly a century. May make an interesting article.

Hi Michael, it’s not so much that anatomical details were overlooked as much that (a plurality of) dinosaur workers’ conception of “genus” has shifted. There’s no measurable threshold separating two species in one genus from two species in separate genera – it’s entirely a matter of a taste and convention. There’s a good discussion of how this applies to dinosaurs here: https://svpow.com/2009/09/12/to-b-b-or-not-to-b-b-or-so-what-is-a-%E2%80%9Cgenus%E2%80%9D-anyway/

Well said. I was referring too a 2015 study of Diplodocidae by Emanuel Tschopp, Octavio Mateus and Roger Benson https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4393826/ (I think I got the article down, bad with computers).

I’m personally not convinced 100%, that’s why it’s wrird as they didn’t just study clusters of stuff with names but every specimen one by one and counted the variables but eight different but somewhat similar species is hard too swallow.

“However, when Osborn heard about this he threatened to ruin Holland’s career if he went through with it.”

Is there any documentary evidence of this, or is it all secondary and tertiary sources?

The primary source that comes to mind immediately is Holland’s Heads and Tails article (https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/37656#page/5/mode/1up), where he lays out the evidence for the Carnegie quarry skull being the true Apatosaurus skull, and says that Osborn “dared” him to use it in his museum’s mount. But you’re right, this is to some degree constructed/assumed by secondary authors based on Osborn’s standing in the field and general demeanor toward other colleagues.

There is definitely something funny about Holland’s language in that paper. So weirdly deferential, sort of saying “I am definitely right about this” and then sort of saying “But you guys know best”.