Lincoln, Nebraska is home to a legendary giant. The University of Nebraska State Museum, known locally as Morrill Hall or Elephant Hall, has the largest mammoth skeleton on display anywhere in the world. “Archie” the columbian mammoth is literally a giant among giants. 14 feet tall and striding on bizarre, stilt-like legs, he towers over the twelve other extinct and extant proboscidians (ten skeletons and two taxidermy mounts) in the museum’s great hall.

Like the Field Museum’s Sue the Tyrannosaurus, Archie is not only a scientific specimen, but something of a mascot. The mammoth is regularly cited as the museum’s star attraction. Its image adorns museum merchandise, and a dancing costumed Archie shows up at local schools and on game days. A bronze sculpture of a fur and flesh Archie created by local artist Fred Hoppe was placed outside the museum’s entrance in 2006, and it is apparently traditional for students to slap its outstretched forefoot for luck. At the center of it all, though, is the real mounted skeleton, which has been on display for 84 years and admired by generations of visitors.

The bronze Archie statue outside the University of Nebraska State Museum. Source

Archie’s skeleton was famously discovered by chickens. In 1921, southwest Nebraska farmer Henry Kariger noticed that his chickens were pecking at some white minerals eroding out of a hillside. Thinking the substance would be a good source of lime for his flock, Kariger started collecting it and adding it to their feed. Eventually the hill eroded further, and Kariger realized he had something more impressive than lime deposits – it was the jaws and teeth of a giant animal.

On November 14, Kariger sent a brief handwritten letter to Erwin Barbour, director of the Nebraska State Museum, describing his find. A geologist and paleontologist, Barbour started his career as O.C. Marsh’s second-in-command at the United States Geological Survey. In 1891, Barbour took the dual posts of Director of the Department of Geology at the University of Nebraska and Nebraska State Geologist. He was appointed Director of the State Museum shortly thereafter, and spent the next fifty years scouring the Nebraskan countryside for fossils to build the museum’s collection. Barbour replied to Kariger two weeks after receiving his letter, informing the farmer that he had found a mammoth, and that he was “entirely sure of this without seeing it.”

Barbour typically received dozens of letters about fossil finds every year, and he gave Kariger the same instructions he gave everyone else: avoid handling the fossils, and absolutely refrain from attempting to extract more bones from the ground. Barbour had seen countless fossils destroyed by overeager members of the public trying to pry them out by hand, or with crowbars. He informed Kariger that the museum would pay for an important find, but only if it was kept intact. Barbour requested that Kariger leave the fossils until the spring, when a museum crew could come out and assess them.

Barbour soon discovered that Kariger had contacted a number of other museums, shopping his find around in an effort to get the best price. In a letter, Kariger informed Barbour that he had been told he had a giant sloth, and that it was exceptionally rare. Barbour held firm, repeating that the find was certainly a mammoth and that he could look at it in the spring. Apparently impatient, Kariger decided to ignore Barbour and got to work excavating the rest of the skeleton, hauling the bones out of the hillside with a team of horses. Miraculously, Kariger did not completely destroy the fossils in the process. With a good portion of a mammoth skeleton in his possession, Kariger brought his find to Lincoln the following summer to display it at the state fair. It was here that Barbour met Kariger – and his mammoth – for the first time. Barbour was suitably impressed, and immediately wrote to Henry Osborn of the American Museum of Natural History, describing the skeleton as complete save for its tusks and the lower portions of its limbs.

According to an account by Walter Linnemeyer (who was about six years old at the time), local authorities discovered that Kariger was selling bootlegged whiskey out of the back of his tent at the state fair, and confiscated both the whiskey and the fossils. Although this makes for an exciting story, Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Manager George Corner confirms that the skeleton “was not confiscated by the Museum or anyone else and then given to the Museum.” In fact, documents in the museum archives confirm that Barbour paid Kariger $250 for the fossils, and that the entirely amicable transfer occurred at the fair in 1922. Since no other documentation about Kariger being involved in illicit sales has surfaced, we must assume that the story is, as Corner puts it, “a product of the times.” Prohibition was the law of the land in 1922, and rumors about sources of illegal liquor must have been common. One might also speculate that anti-government sentiments in rural communities may have played a role in the myth-making.

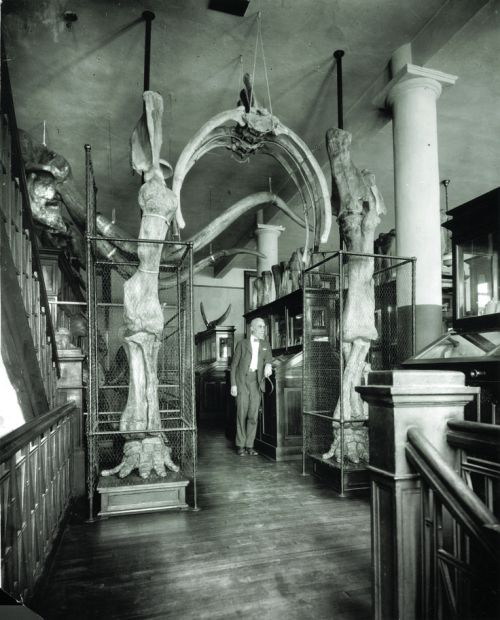

Barbour poses with Archie’s legs in 1925. Source

Another reason to discount the notion that Kariger’s fossils were seized is that he and Barbour maintained a friendly relationship for years afterward. In December 1922, Kariger wrote to Barbour to inform him that he had found one of the missing tusks, but that he had damaged it while removing it from the ground (it didn’t help that his pigs had chewed on it a bit). Barbour once again asked that Kariger leave any further finds buried, reminding him that the museum would pay more for undamaged fossils. Barbour and his student William Hall made the two-day journey to Kariger’s farm the following June. They stayed with the Kariger family for five nights, paying them for room and board, as well as the services of a draft team. Even after resorting to dynamite to blast away the rest of the hill, Barbour went back to Lincoln empty handed. Still, both he and the Karigers enjoyed the experience, and they fondly reminisced about the trip in subsequent letters.

Barbour initially published the Kariger mammoth as a new species, Elephas maibeni, after museum donor Hector Maiben. Osborn’s monograph on proboscidian evolution, posthumously published in 1936, redescribed it as Archidiskodon imperator (hence “Archie”). Archidiskodon has since been folded into Mammuthus columbi, or the columbian mammoth, a species which ranged throughout the western United States and Central America.

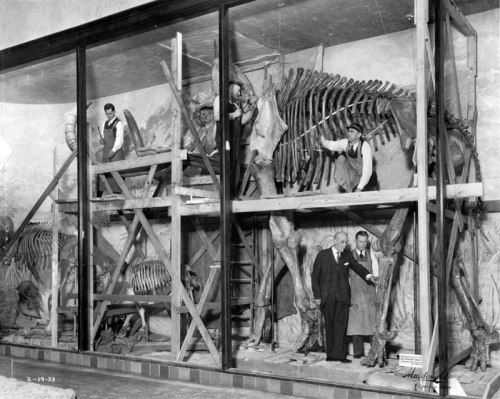

Barbour oversees his impeccably-dressed staff as they mount Archie’s skeleton. Source

When the University of Nebraska State Museum acquired Archie in 1922, space was severely limited. Collections were already stuffed into attics, cellars, and even the steam tunnels between university buildings. Nevertheless, Barbour ensured that at least part of the record-sized mammoth was on display. In 1925, he mounted the forelimbs and part of the torso, forming an archway at the museum’s entrance. A new, larger museum building funded by donor Charles Morrill was completed two years later, and the Kariger mammoth was immediately a candidate for display as a complete mounted skeleton. Barbour sent preparator Henry Reider out that summer to collect isolated mammoth bones that could fill in Archie’s incomplete legs. Soon work on the full mount was underway, with contributions from Reider, Eugene Vanderpool, Frank Bell, and others. The 14-foot tall, 25-foot long mount took years to construct, but was finally completed in the spring of 1933.

Even before Archie was complete, it was clear that the new museum’s central hall would be a showcase for fossil elephants. The lineup of mounted skeletons, which has not changed significantly since the mid-20th century, includes two columbian mammoths, an American mastodon, Stegomastodon, Gomphotherium, Amebelodon, Eubelodon, a pygmy mammoth, and contemporary African and Asian elephants. Elizabeth Dolan provided two parallel background murals which depict elephants around a forested watering hole in an impressionistic style. Today, a contemporary mammoth mural by Mark Marcuson adorns the far wall.

The spectacular elephant hall (Archie is along the left wall, blocked by the taxidermy elephants from this angle). Source

84 years after it was first assembled, the skeleton of Archie the mammoth is a Nebraska icon. Indeed, this mount and the hall it resides in have become a time capsule, a landmark to return to again and again for generations of visitors. Nevertheless, even the most beloved icons are not completely safe. The Nebraska state legislature has repeatedly hit the State Museum with budget cuts, including an astonishing 50% cut in 2003 accompanied by the dismissal of several tenured curators. Thanks to inspired leadership by Director Priscilla Grew, the museum re-earned its accreditation in 2009 and became a Smithsonian Affiliate in 2014. Still, the series of events is a sobering reminder that while museums exist as a public service, they are also dependent on public support. Funding museums must be a top priority if we want legendary displays like Archie to be on exhibit for generations to come.

Many thanks to George Corner for answering my questions about Kariger’s mammoth. Any factual errors are my own.

References

Barbour, E.H. 1925. Skeletal Parts of the Columbian Mammoth Elephas maibeni. Bulletin of the Nebraska State Museum. 10: 95-118.

Corner, R.G. 2017. Personal communication.

Debus, A.A. and Debus, D.E. 2002. Dinosaur Memories: Dino-trekking for Beats of Thunder, Fantastic Saurians, “Paleo-people,” “Dinosaurabilia,” and other “Prehistoria.” Lincoln, NE: Authors Choice Press.

Knopp, L. 2002. Mammoth Bones. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment. 9:1: 2002.

Linnemeyer, W. and Nutt, M. 2009. Mammoth Bones and Bootleg Whiskey. The Mammoth: A Newsletter for the Friends of the University of Nebraska State Museum. August 2009.

Osborn, H.F. and Percy, M.R. 1936. Proboscidia: A monograph of the discovery, evolution, migration, and extinction of the mastodonts and elephants of the world. New York, NY: American Museum Press.

With the largest mammoth skeleton on display here, I wonder what skeleton the mammoth had on display…

I saw more of this room on it’s website and was truly impressed, it’s one of the finest display rooms I’ve seen!

It’s well lit, not claustrophobic, doesn’t have cheep “in your face” displays but honest frank science that treats the displays with respect and those visiting as well.

Then I just saw a website!

THIS WAS THE BEST THING EVER