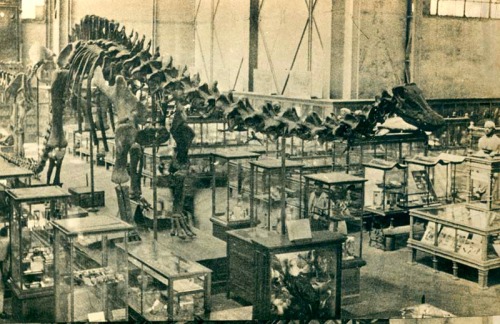

The first cast of the Carnegie Diplodocus holds court at London’s Natural History Museum. Source

The story of Andrew Carnegie’s Diplodocus will surely be well known to most readers. As the legend goes, Carnegie the millionaire philanthropist saw a cartoon in the November 1898 New York Journal depicting a sauropod dinosaur peering into the window of a skyscraper. He immediately contacted the paleontology department at the newly established Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, and offered ample funding to find a sauropod skeleton for display. So began a frantic competition among the United States’ large urban museums to be the first to collect and mount a sauropod—the bigger the better.

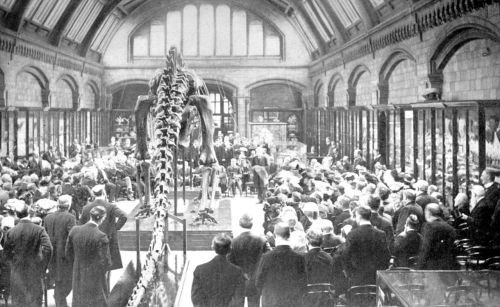

The American Museum of Natural History was first across the finish line, unveiling their composite Apatosaurus in February of 1905. By that time, the Carnegie team had already found a sauropod skeleton of their own—a Diplodocus—near Medicine Bow, Wyoming. Unfortunately, they had nowhere to display it, as the Carnegie Museum building was still far from finished. Unwilling to be bested by his New York competition, Andrew Carnegie offered his chum King Edward VII a complete plaster replica of the Diplodocus, and hired a team of modelmakers to help make it happen. The arrival of the facsimile Diplodocus at the British Museum (now the Natural History Museum) in London was celebrated with a white tie event presided over by Carnegie and Baron Avebury, who spoke on behalf of the king. The London Diplodocus was on display two months after the AMNH Apatosaurus, and the original skeleton was unveiled in Pittsburgh in 1907.

That’s usually where the Diplodocus story ends, with a footnote that nine more Diplodocus replicas were later manufactured and presented to heads of state throughout Europe and Latin America. I’d like to explore those subsequent displays in more detail. The Carnegie Diplodocus was the first mass-produced dinosaur, and by 1932 it appeared in no less than ten virtually identical displays across three continents. Taylor characterizes Carnegie’s sauropod as “the single most viewed skeleton of any animal in the world”, and its scientific, social, and even political ramifications are both wide-reaching and fascinating.

Building a Sauropod

The real CM 84 has been displayed in Pittsburgh since 1907. Source

The Diplodocus in question is specimen CM 84, recovered in 1899 in Albany County, Wyoming. The skeleton was about 60% intact and remains one of the most complete sauropod specimens ever found. The ubiquitous John Bell Hatcher described the fossils in 1901, coining the new species Diplodocus carnegiei after the project’s benefactor. Arthur Coggeshall of the Carnegie Museum was primarily responsible for preparing and casting the fossils. He was initially supervised by Hatcher, but William Holland took over when Hatcher died in 1904. Holland deferred to Hatcher’s judgement in most cases, although he was not shy about voicing his disagreement. For example, Hatcher had reconstructed the Diplodocus forefeet with slightly elevated digits, but Holland (incorrectly) thought they should be flat and splayed.

As is typical of dinosaur mounts, the incomplete primary specimen was supplemented with other fossils to produce a full skeleton. The skull, for instance, was a cast of USNM 2673, a specimen on display at the Smithsonian. A number of missing bones, including most elements of the forelimbs, were sculpted using a smaller Diplodocus specimen for reference. Although it took longer to produce than the AMNH Apatosaurus, contemporary paleontologists generally agreed that Carnegie’s Diplodocus was the superior sauropod mount. Not only was its pose more natural and lifelike, but the underlying steel armature was cleverly hidden. It’s difficult to overstate the challenges of assembling a mounted skeleton on this scale, and in its day the Diplodocus was the best in the world.

Roll Call

The Chopo University Museum in Mexico City received the 9th Diplodocus cast in 1929. Source

As mentioned, the first replica Diplodocus was unveiled in London in 1905, and the original fossils were ready for display in 1907. French and German dignitaries were present at an event in Pittsburgh celebrating its completion, and Andrew Carnegie promised both countries Diplodocus casts of their own. Once again, Coggeshall and Holland led the creation of the new mounts, a task they would repeat many times in the years to come. Playing precisely to cartoonish national stereotypes, the Germans provided a detailed plan and ambitious schedule for the project, while the French acted coy, then threw a lavish party when the mount was ready. Diplodocus replicas were on display at the National Natural History Museum in Paris and the Humboldt Museum in Berlin before the end of 1908, but the Pittsburgh team already had orders for a new batch of mounts. By early 1910, three new Diplodocus were on exhibit at the Museum for Paleontology and Geology in Bologna, Italy, the Natural History Museum in Vienna, Austria, and the Zoological Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. The La Plata Museum in Buenos Aires, Argentina and the National Museum of Natural Science in Madrid, Spain received their Diplodocus mounts in 1912 and 1913, respectively, bringing the total number of replicas up to eight by the onset of World War I.

The war put a damper on this friendly exchange of dinosaurs, and Carnegie’s death in 1919 brought the Diplodocus diaspora to a temporary end. However, in 1929 Louise Carnegie, wife of Andrew, commissioned an additional cast as a gift for Alfonso Herrera of the Chopo University Museum in Mexico City. Herrera originally asked for a bronze cast for outdoor display, but when this proved prohibitively expensive, a plaster version was produced instead. In 1932, the Carnegie Museum traded a Diplodocus replica for a collection of German fossils from the Paleontological Museum in Munich. This copy has never been mounted or displayed. The last Diplodocus cast from the original molds was forged in 1957. Made from concrete, this mount was displayed outdoors for many years at the Utah Field House Museum in Vernal, Utah.

The 11th and final facsimile Diplodocus made from the original molds was this concrete version, on exhibit in Vernal, Utah for many years.

Most of the historic Diplodocus mounts remain on display today. The London Diplodocus was taken off exhibit during World War II, but in 1979 it was given a position of honor in the museum’s entrance hall. Later, it was completely restored and remounted with its tail held aloft. The Berlin, Buenos Aires, and Bologna Diplodocus mounts have also been upgraded with modern poses, but the others retain their historic, tail-dragging posture, looking exactly as they did a century ago. The St. Petersburg mount was circulated among a number of Russian museums, and may have been destroyed in an effort to make new molds from the bones (Edit: The Russian mount is still on display at the Orlov Museum for Paleontology—see comments). The concrete Diplodocus in Vernal has likewise been retired, but it was used to create two new casted skeletons, now on display in Utah and Nevada.

Opportunities for Science

The weird bow-legged Diplodocus in St. Petersburg looks more like the original USNM Triceratops than Tornier’s take on the sauropod. Source

The sudden availability of identical Diplodocus skeletons presented an unusual opportunity for international scientists, allowing researchers based thousands of miles apart to study and compare notes on the same bones. Perhaps inevitably, a few European scientists were not happy with Holland and Coggeshall’s take on the sauropod. The best-known dissenter was Gustav Tornier, who rejected the straight-limbed reconstruction of Diplodocus, arguing instead that the sauropod sprawled like a crocodile. The German scientist provided an illustration of this alternate stance, in which the poor dinosaur’s arms appear to project from the base of its neck. Holland responded with a particularly harsh rebuttal (backed by several European scientists), and Tornier declined to push the issue further in print.

Dinosaurs for everyone

Diplodocus cast number seven at the La Plata Museum in Buenos Aires. Source

The most lasting influence of the Carnegie Diplodocus is certainly it’s cultural impact. If any one specimen can be credited with inspiring the global popularity of dinosaurs, it was this one. Thanks to Carnegie, citizens of 11 different nations had their first opportunity to stand in the presence of a giant dinosaur, and to experience the scale and splendor of a creature that completely dwarfed any modern land animal. In every nation where a new Diplodocus was installed, the local press adored the creature, never failing to point out its tiny head and presumed stupidity. Diplodocus was an endearing oaf, and for a time, its name was synonymous with dinosaurs and prehistory in general.

What was the significance of Diplodocus to all these people? It’s difficult not to think of it as a vanity project for Andrew Carnegie*, an opportunity to rub shoulders with European royalty and flaunt his wealth and generosity. One might also consider the Diplodocus an expression of America’s economic and technological might, or perhaps a harbinger of the United States’ role in globalization and mass production. French writer Octave Mirbeau seemed to be thinking along those lines when he lamented the mighty dinosaur being reduced to a crass, populist display. According to Carnegie himself, however, the goal was nothing less than world peace: he wanted to bring people together over their shared enthusiasm for the dinosaur. Too bad World War I came along and ruined the sauropod love-in.

On both sides of the Atlantic, Diplodocus was a shared point of reference and a beloved symbol. Most commonly, Diplodocus was the butt of a joke: from politicians to athletes to heavy machinery, anything big, slow, and not especially bright was likened to the dinosaur. My favorite anecdote on the subject comes from Nieuwland: during World War I, soldiers from different nations with different languages had the word “Diplodocus” in common, and used it to describe the heavy, plodding tanks.

Today, we think of Diplodocus and it’s ilk very differently. Sauropods weren’t ungainly dolts—they were surprisingly nimble and extremely successful megaherbivores, unchallenged in their dominance for 140 million years. Still, it’s difficult to think of single fossil that has matched the global cultural impact of CM 84. There are far more copies of Stan the T. rex on display, and Sue is widely known by name, but really, the only contender that even comes close is Archaeopteryx. With eleven versions still on display, Carnegie’s legendary Diplodocus lives on.

References

Brinkman, P.D. 2010. The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush: Museums and Paleontology in America at the Turn of the 20th Century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Holland, W.J. 1906. The osteology of Diplodocus Marsh with special reference to the restoration of the skeleton of Diplodocus carnegiei Hatcher, presented by Mr. Andrew Carnegie to the British Museum, May 12, 1905. Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum. Vol. 2, No. 6, 225-278.

Nieuwland, I. 2010. The colossal stranger: Andrew Carnegie and Diplodocus intrude European Culture, 1904-1912. Endeavour. Vol 34, No. 2.

Taylor, M.P. 2010. Sauropod dinosaur research: a historical review. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. Vol. 343, pp. 361-386.

This is the best review of the Carnegie Diplodocus casts I’ve read on the web. Many thanks for posting it.

Hi, great story isn’t it? I’m nearly ready with my Ph.D. Thesis about these casts. However, I can shed some light on the ‘Petersburg’ Diplodocus. The picture shows the cast *after* it was moved, along with the Russian Academy of Sciences, to Moscow. It was put up in the Neshkuchny Palace, the gardens of which nowadays make up Gorky Park. Although I’m not very sure about who was involved with this re-mount (the archives largely went astray amidst the collection’s many moves), it looks as though they took their cue from Abel’s 1910 monograph (Abel, Othenio. “Die Rekonstruktion des Diplodocus.” Abhandlungen der K.K. zoologisch-botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 5 (1910): 1-59, 2 plates).

Interesting, thanks for clarifying. Is it correct, then, that the Russian copy was destroyed?

I’d be very interested in reading your dissertation when it’s ready!

Sorry, should have given some dates. The copy was moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow in the early 1930s, and was on view in the Palace between 1937 and 1941, when the German advance caused the Soviet government to send it to Alma Ata in Kazakhstan for safe-keeping. It was then on view again in the Neshkuchny from 1944 to 1957, when the museum had to be closed for a variety of reasons. It then stayed in storage until 1990, when it became one of the centerpieces of the new Orlov museum for paleontology, where it can still be seen – in a somewhat odd mount with its full Hollandian complement of four claws on the manu. Certainly the most well-traveled of the Diplodocuses, then.

On a side note, I consider Holland’s tale of the St. Petersburg Diplodocus crashing in on him to be highly suspect.

That’s three claws of course, not four. Sorry.

Absolutely stunning. Thank you.

Thank you for such an interesting article on one of my favourite dinosaurs! I’m about to write an article on the Argentinosaurus for an online magazine so I found your post intriguing!

Reblogged this on sotonz's Blog.

Awsome!

Reblogged this on rib76004 and commented:

My nephews would LOVE to see this!!

Fantastic piece of history – thanks.

Reblogged this on Dr Samuel George and commented:

Such a wonderful sight when you enter the natural history museum.

So cool!

This is beautifully written, great post

Reblogged this on The Jurassic Inquirer.

Great article. It’s nice to nkow the story behind those skeletons.

Impressive read, even months after I found this. Thanks to it I now know about the other casts of Dippy around the world, including Russia, mexico, and Argentina.

While on the subject, the Cleveland Museum will be revivig this idea by hosting a cast of Dippy for a few months, adding a tweth cast no matter how short-lived.

https://www.cmnh.org/science-news/blog/january-2022/happy-deinstallation

I’m pretty sure the one going to Cleveland is the London NHM Dippy, which recently finished it’s tour.

“The skull, for instance, was a cast of USNM 2673, a specimen on display at the Smithsonian.”

Belatedly, but I hope you still read this … What is your reference for this? I am trying to figure out in more detail what the composition of the Carnegie Diplodocus really is.

Hey Mike, it’s in Holland 1906, pg. 227 https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/38966975#page/309/mode/1up

Super-helpful and really quick, too! Many thanks indeed.

Do you know if that’s also the skull that has been used in the various casts of the Carnegie mount?

They used it as a base. There was also a skull from the site, broken, but it was still full of data. I think they used USNM 2673 as abase with influence from the broken one.

I’ve looked into this a bit more. Here’s what I have in an in-progress manuscript, if you’re interested.

—

CM 84, the specimen from which the Carnegie mount is mostly assembled, does not itself include a skull. Holland (1906:227) explains that the skull supplied to British Museum (now the Natural History Museum) as part of the Diplodocus cast presented to it in May 1905 was a composite sculpture based on several specimens.

• The posterior portion was modelled on material from CM 662 (illustrated by Holland 1906:plate XXVII–XXVIII; now HMNS 175). This specimen was initially referred by Holland (1906) to the genus Diplodocus and subsequently made by him the holotype of the new species “Diplodocus” hayi (Holland 1924). The species has since been moved to its own new genus Galeamopus by Tschopp et al. (2015:267).

• The remainder of the skull was based on USNM 2673 (illustrated by Holland 1906:plate XXIII–XXV), the skull on which Marsh (1896:175–179) had primarily based his description of the skull of Diplodocus. With the USNM’s permission, the Carnegie Museum made a cast of this skull, of which only the left side had been fully prepared. They used this to restore the missing half. Ironically, this skull has since been referred by Tchopp et al. (2015:228) to Galeamopus, meaning that both the fossils on which the Carnegie mount’s skull were based are now considered to belong to that genus.

The skull used in the Barosaurus mount is shown in a 1991 photograph (Figure C). It can be fairly confidently confirmed as the same composite illustrated by Holland (1906:figure 1) “as placed in the restoration at the British Museum”, and by Nieuwland (2019:figure 5.3) in a photograph of a worker at the Muséum Natonal d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France, with the plaster skull of their Diplodocus cast in 1908.

In the Carnegie mount, the skull was replaced in XXX year by a cast of the Diplodocus sp. skull CM 11161 (Matt Lamana, pers. comm., 2022) — but this change was not been reflected in the Vernal copy of the Carnegie mount, nor therefore in the skull cast from this for the AMNH’s mounted Barosaurus.

Very interesting!

No problem (I happened to get the alert at an opportune time).

I’ve always assumed it was the same skull on all the casts, is there any reason to think otherwise? There couldn’t have been that many other Diplodocus skulls of that quality available at the time…or now for that matter.

Fantastic article on DIPLODOCUS. Loved this dinosaur as a child and stil today. I was fortunate to have led a crew of exhibit construction team featuring two skeletons, one mounted standing on its hind legs, for the Museum of Science and industry in Tampa Florida. We purchase the cast from the late Dr. Jim Madsen of Salt Lake City. The skeletons were mounted with armatures by RCI from Ontario Canada. The one cast mounted standing upright was the second sauropod skeletn mount in that stance. We based the mounting on the Barosauers skeleton in the AMNH in New York. During construction I had difficulty fitting both specimens in our lobby space. I used measurements of the believed lengths based on several scientific papers. All text at that time gave us an estimated length of 85 feet. I asked Jim to lay the skull and axial skeleton out at his lab and measure it. We came up with 75 feet long. Once we establish the exact length I could fit these cast accurately in the space required. These cast still are providing new information and knowledge. Those disappointed that Dippy is a little shorter should not fret as now research is finding that this individual was most likely a juvenile and not full grown.

Thanks David, that’s a great story!

American Dinosaur Abroad: A Cultural History of Carnegie’s Plaster Diplodicus.

Published in 2019