I generally use this blog to write about other people’s work, but today I’m going to turn the tables and share a project I’ve been involved with for the past couple years. As of this month, the new interpretive area at Laurel, Maryland’s Dinosaur Park is (just about) complete. I’m proud of my own contributions, and ecstatic with all the work my immeasurably talented and dedicated colleagues have done to bring this project to fruition.

Dinosaur Park is a 41-acre site operated by the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission that preserves the most productive dinosaur fossil quarry in the eastern United States. Historically known as the Muirkirk quarry, this location has been a known source of dinosaur material since 1858. Fossils were first discovered by ironworkers collecting siderite for processing at the nearby Muirkirk ironworks. Later, O.C. Marsh, John Bell Hatcher, Charles Gilmore, Richard Lull and other prominent paleontologists would collect or study fossils from this deposit. The site was largely forgotten for most of the 20th century, but in the 1980s Peter Kranz, Tom Lipka, and others relocated it and began unearthing new material. Highlights included a massive sauropod femur, basal ceratopsian teeth, and the only Mesozoic mammal fossils ever found east of the Mississippi River.

The Muirkirk quarry produced some of the first dinosaur fossils to be scientifically studied in North America, and as such conceptions of its position in geologic time have understandably changed over the years. Marsh assumed the site was Jurassic in age because of the presence of sauropods, but Gilmore later revised it to Cretaceous. Based on pollen data, we can now place the site (and the Patuxant Formation as a whole) at the Aptian-Albian boundary in the Lower Cretaceous. Contrary to older proposals, the Muirkirk dinosaur fauna has more in common with the middle strata of the Cedar Mountain Formation in Utah than the Wealden Group in England.

Excavating a sauropod femur at the future site of Dinosaur Park in 1991. Photo courtesy of Pete Kroehler.

Dinosaur Park fossils aren’t much to look at, but they are remarkable for their diversity. This is a record of a complete ecosystem.

Thanks to some determined lobbying, the M-NCPPC (a bi-county organization that administers parks and urban planning) acquired the Muirkirk site and formally dedicated Dinosaur Park in October 2008. From its inception, Dinosaur Park was conceived as a citizen science project. During school programs and regularly scheduled open houses, visitors are invited to take part in ongoing prospecting for fossils. These programs emphasize stewardship of natural heritage, rather than treasure hunting, and to date visitors have discovered thousands of specimens. All of these fossils are accessioned into the county’s collection for research and education, and important specimens are turned over to the National Museum of Natural History for final curation (search the NMNH Paleobiology collections database for “Arundel” to view this material).

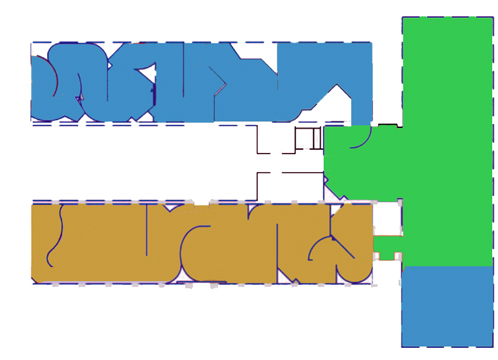

Back in 2008, there wasn’t much to Dinosaur Park beyond the fossil site, a protective fence, and a small gravel parking lot. There were always plans to further develop the site, however, and thanks to the Park’s ongoing popularity we were able to kick off the phase II construction in 2016. The project involved developing the entrance area with exhibits and visitor amenities. There wasn’t a lot of space to work with, and the new facilities would have to do double duty: they needed to be useful both during guided programs and for drop-in visitors during the week (when the fossil site is closed). We ended up with an integrated, multipurpose space incorporating a series of exhibit signs, a garden of “living fossil” plants, a presentation area, a climbable dinosaur skeleton, two picnic benches, and a restroom and drinking fountain.

A number of additions were – to the probable annoyance of my colleagues – the result of me piping up with a last-minute “wouldn’t it be cool if…” suggestion. That’s how we ended up with a life-sized image of the Astrodon femur discovered by the Norden family in 1991, a trail of sauropod footprints, and a series of displays about baby sauropods (perhaps there’s a theme there?).

The content of the exhibit signs was directly informed by formal and informal visitor surveys. We took note of visitors’ most frequent questions, as well as which parts of our old displays were being ignored or misunderstood. For example, lots of visitors wanted to know about the biggest or most important fossils found at the Park. These weren’t illustrated on our old signs, but they’re integral parts of the new ones. Meanwhile, very few visitors were engaging with content about local geology, so those sections ended up being cut.

A section of Shoe’s masterful Cretaceous Maryland mural. Artwork by Clarence Schumaker, courtesy of the M-NCPPC.

For me, and hopefully many visitors, the highlight of the new displays is the spectacular mural created by Clarence “Shoe” Schumaker. Shoe has produced artwork for numerous parks and museums, including several National Park Service facilities, but to my knowledge he had never painted dinosaurs before. Nevertheless, he approached the project with unquenchable enthusiasm, determined to get every detail correct. Working with Shoe was a fantastic experience – I would send him my hasty sketches and random ideas and he would somehow turn them into spectacular imagery. Our goal was to produce an image that would be at home in any nature center. This is an overview of an ecosystem, and the presence of dinosaurs is only by happenstance. The final piece is mesmerizing, and I think its hyper-detailed placidity gives it a certain Zallinger-like quality.

The finished mural was so cool that I couldn’t help but ask for more. One under-reported virtue of the Dinosaur Park collection is that we have sauropod remains from a variety of ages and sizes – from 70-foot adults to tiny hatchlings. I suggested a single image of a baby sauropod to help illustrate these animals’ remarkable growth potential. Shoe turned around and produced two full paintings and a life-sized model. The man is seriously unstoppable.

It’s been a wonderful experience seeing the Dinosaur Park interpretive area come together, and the few places where compromises were made are vastly overshadowed by the many prominent successes. Dinosaur Park is an important resource, both for growing our knowledge of prehistory and for introducing the local community to the process of scientific discovery. I can’t wait to see it continue to grow!