The late 19th century saw a wave of large natural history museums established in urban centers across the United States. From the American Museum in New York City to the Field Museum in Chicago, these institutions were born out of a desire to provide public access to knowledge and culture. Opening its doors in 1884, the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) was part of this trend, but it has always differed somewhat from its peers. For one thing, MPM was (and remains, in part) a municipal project, and its collections are publicly owned. More obvious to visitors, however, are the uniquely crafted, immersive exhibits that have always been a part of this institution’s identity.

Referred to by staff as the “Milwaukee style,” these exhibits de-emphasize cases of artifacts in favor of large-scale theatrical scenes that recreate particular times and places. While the museum boasts a collection of four million natural and cultural objects, the public-facing exhibits favor models, set pieces, and sound effects that immerse visitors in the story being told. This approach started early. In 1890, “father of modern taxidermy” Carl Akeley created his first habitat diorama (a muskrat colony) at MPM. 1965 saw the opening of the locally beloved Streets of Old Milwaukee, a walk-through recreation of shops and houses from the turn of the century. Other examples of the Milwaukee style include a 12,000 square foot, multi-story artificial rainforest, Guatemalan and Indian marketplaces populated by mannequins and taxidermy animals, and some of the biggest, most ambitious habitat dioramas to be found anywhere.

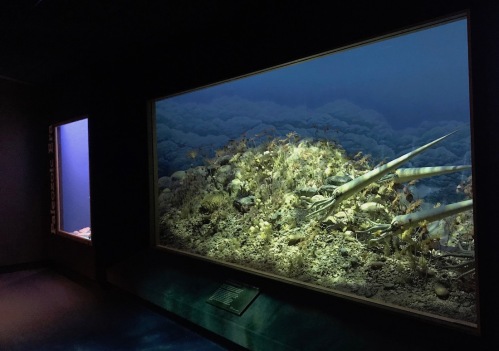

Most pertinent to this blog is the paleontology exhibit, called The Third Planet. Now over 35 years old, The Third Planet is dated scientifically but remains a masterful example of Milwaukee style exhibit design. Its most celebrated component is a 2,500 square foot diorama of a Tyrannosaurus eating a Triceratops in a Late Cretaceous cypress swamp. If you haven’t been to MPM, you may well have seen photos of this display endlessly reproduced in dinosaur books from the 80s and early 90s. Nevertheless, the inception of the exhibit was less about the dinosaurs and more about geology.

According to former Curator of Geology Robert West, The Third Planet was primarily conceived as an exhibit about plate tectonics. MPM’s previous geology and paleontology exhibit, called A Trip Through Time, opened in 1964 and omitted plate tectonics as a unified explanation for geological processes like mountain building, as well as the distribution of plants and animals in the fossil record. While the general principles of continental drift had been around for decades, it wasn’t until the 1960s that the idea became a universally accepted theory underlying all of earth sciences. A Trip Through Time was on the wrong side of that sea change, and West and his colleagues were keen to correct it.

In 1977, the community-led support organization Friends of the Milwaukee Public Museum provided $20,000 to start developing a new geology exhibit. This seed money allowed the museum to assemble a core concept team: content advisors West and fellow curator Peter Sheehan, designers Jim Kelly and Vern Kamholtz, and educators Barbara Robertson and Martha Schultz. The team began by visiting other museums as a benchmarking exercise, and eventually produced a draft script and statement of purpose for the new exhibit.

The limestone cavern is modeled after Cave of the Mounds in Blue Mounds, Wisconsin. Photo by the author.

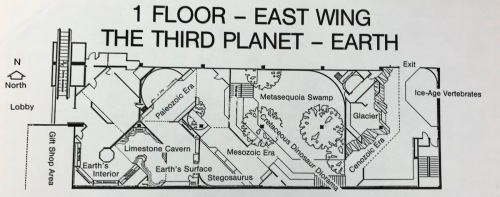

Plate tectonics — and the idea that the Earth and life on it have been in constant motion throughout history — was to be the unifying theme of the proposed exhibit. Visitors would begin with an orientation film, then proceed on a walk through time, visiting a series of reconstructed habitats from the distant past. Highlights would include a limestone cavern, a Carboniferous coal swamp, life-sized dinosaurs, and the edge of an advancing glacier with an enterable ice cave. The overall budget was $1.9 million, a comparatively modest figure made possible by the extensive in-house production facilities already available at MPM. Funded in part by private donations and a National Science Foundation grant, the exhibit was green-lit to start production in early 1979.

While the scientists and collections staff worked on deinstalling A Trip Through Time and gathering specimens for the new exhibit, designers Kelly and Kamholtz started producing floor plans and miniatures. Script revisions were an ongoing process, informed by the availability of specimens and practical realities of construction.

MPM’s historic mastodon was joined by new mounts of a moa and an ice age bison constructed by Rolf Johnson. Photo by the author.

The in-house art department had the most daunting job. A team including Wendy Christiansen, Floyd Easterman, Mike Malicki, and Greg Septon created no less than six distinct immersive environments from scratch, and designed an assortment of life-sized animals to populate them. Bob Frankowiak, Carol Harding, and Syl Swonski painted the various murals and illustrations. Only a few pieces were purchased, among them a pair of dinosaurs from the famed Sinclair Dinoland exhibition at the 1964 World’s Fair. The Struthiomimus is a Dinoland original, while the Stegosaurus is a duplicate made from the original molds.

The exhibit artists put everything they had into the Tyrannosaurus scene. This was to be the first life-sized diorama of dinosaurs in their environment ever built, so it had to be spectacular. Artists created hundreds of individual fronds and leaves, pressed dozens of footprints into the simulated mud, and populated the scene with animals large and small. Although the bloody spectacle of T. rex digging into the side of Triceratops steals the show, the scene also contains a paddlefish, a Champsosaurus, a tiny mammal, a loon-like bird, and more. No detail was too small: the Tyrannosaurus even has drool (made from clear plastic lacquer) dangling from its teeth. Computer-controlled lighting (state-of-the-art in the early 1980s) cycles through different times of day, and a richly-layered soundtrack of animal calls brings the motionless tableau to life. All told, the diorama was nearly five years in the making from the earliest drawings to final installation.

The Third Planet opened to the public on October 8th, 1983. 28,518 visitors attended opening events across three consecutive weekends, and media coverage was universally positive. The introductory film on plate tectonics even won a Golden Eagle Film Award in the Science category. Museum director Kenneth Starr (no relation to the former independent counsel) handled the occasional visitor complaint personally. In one amusing reply to a visitor complaining that the T. rex diorama was too gory, Starr wrote that “such is the way that life was and still continues to be in the natural world. We do no one any educational courtesy by portraying life a la Walt Disney and Fantasia.”

For the most part, The Third Planet is still exactly as it was 35 years ago. The most significant change was the addition of a mounted Torosaurus skeleton to the exhibit entrance in 1991, replacing the orientation film. The fossils were found by Bob and Gail Chambers during one of the museum’s “Dig-A-Dinosaur” summer field programs. Rolf Johnson coordinated a team of volunteers to prepare and mount the skeleton, all in view of the public. The now-classic Tyrannosaurus diorama was updated in 2017 with enhanced lighting and sound. According to regular visitors, the scene is now louder and more intense than ever. Two dromaeosaurs were removed from the diorama so that museum artists could outfit them with feathers, but they have yet to be reinstalled.

Torosaurus had a colossal head. At nine feet long and nearly as wide, it is rivaled only by modern whales. Photo by the author.

Nevertheless, much of the content in The Third Planet is decades out of date. This is largely the result of a major budget crisis MPM faced, and overcame, in the early 2000s. A CFO’s mismanagement put the museum eight figures in debt, and 40% of staff left or were laid off. The museum had to fight for its existence in a conservative-leaning state, fending off unhelpful suggestions to privatize, sell off collections, or close altogether.

Happily, MPM is now completely out of debt and looking toward the future. The museum’s collections facilities are in poor shape, and significant renovations would be needed for the institution to maintain its accreditation. Rather than continuing to lobby Milwaukee County (which owns the building the museum occupies) to update the structure, MPM is looking to move to a new, purpose-built location elsewhere in the city. Earlier this year, MPM revealed a series of conceptual images, all of which emphasize bright, open interiors and a mix of indoor and outdoor displays.

As explained in the museum’s FAQ document about the move, the best historic dioramas and exhibits would be moved to the new location. That means that, assuming MPM can find a location and funding for the new building, highlights of The Third Planet would surely be restored and re-contextualized in any future incarnation of the institution. At the very least, the prominence of dinosaurs and fossils in nearly all of the conceptual images makes it clear that paleontology exhibits will be part of MPM for a long time to come.

Many thanks to Archivist Ruth King for her generous assistance in accessing materials used for this article.

My childhood museum which still retains much affection from me. I remember when the geology exhibit closed for renovations and it seemed like an eternity to wait for it to reopen as “The Third Planet.” That T. rex exhibit took my breath away when my parents took me to see the exhibit not long after it reopened. I still like it. The museum loves the tiny details, as you pointed out, and it really creates environments that make you want to explore and experience, not just blaze through to see what’s next.

Thanks for sharing your recollections! Do you remember much of the exhibit from the 60s and 70s?

I was born in ’75, so I have no memories of what was there before.

How did they get the Moa, it’s not as easy as it used too be when it come from getting them from their original source.

Other then that I like this museum, it’s dated sure but they get a good message while being modest and not cramming down the visitors throats.

The moa (and bison) was already in the collection when The Third Planet was built, it just had never been mounted for display before. Not sure how the museum acquired it originally, or when.

Makes sense, Moa were quite popular overseas at one point, in 1839 (or thereabouts) the first remains were found they were sent too the UK where Richard Owen (may be an interesting guy too write about) got a fairly accurate identification of them that was soon proven 100% when several complete skeletons he gained his reputation and then on always had a soft spot for them.

And until recently Dippy’s best friend in the London Natural History Museum is a complete Dinornis robustus.

And I remember in your AMNH through the ages articles one of their first skeleton mounts was a Moa.

Now it’ll be impossible too send them overseas.

Not just the dinosaurs, there looks to be a massive walkthrough silurian reef diorama.

Wow, nice find.

Thank you.

I wonder if the new museum will include not just a Silurian diorama and likely a cretaceous diorama, but an ice age/pleistocene diorama, including both the mastodon and other wisconsin life, like Cervalces scotti.

To add, the introductory film played on a loop near the entrance of The Third Planet in the early days of exhibit was ‘Dinosaur’, a 17-minute claymation short created by Will Vinton in 1980.