Earlier this month, I had the a chance to see the “Dueling Dinosaurs,” which debuted at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Science (NCMNS) in April. Consisting of virtually complete skeletons of a tyrannosaur and Triceratops preserved side-by-side, this fossil is either the find of the century, or just another example of overhyped, overstudied, and overpriced Hell Creek dinosaurs—it depends on who you ask. But NCMNS has made it more than that, placing the fossil at the center of an ambitious project to improve science literacy by removing all barriers to the process.

Commercial collector Clayton Phipps discovered the skeletons in 2006, on private ranchland in Montana. Having never worked on anything so large before, Phipps teamed up with the Black Hills Institute for the initial preparation and assessment of the fossil. The skeletons were put up for auction in 2013, resulting in what has become a familiar din of competing voices. The sellers heralded the rarity and quality of the fossil, proclaiming it to be a clear example of dinosaurs that perished while locked in combat. Paleontologists countered that a fight-to-the-death scenario was unlikely, and without scientific study, the circumstances of the dinosaurs’ demise could not be known. Furthermore, in the event that the fossil went to a private buyer, there would be no opportunity to study it. The so-called Dueling Dinosaurs were poised to become yet another example of a high-profile specimen sold into private hands, where they could never contribute to scientific and public knowledge.

As it happened, the auction was a failure, and bidding never reached the reserve price. Behind the scenes, however, the Friends of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Science—a non-profit organization that supports the state-run museum—had put forth an offer of six million dollars for the fossil. To be clear, a mid-sized public museum like NCMNS absolutely does not have $6 million on hand for specimen acquisition. The funding came from private donations solicited by the Friends organization.

The offer was accepted, but there was another hurdle: a legal challenge over ownership of the land the fossil was found on. In Montana, surface rights (ranching, farming, etc.) and mineral rights (oil, coal, uranium, etc.) to the same parcel of land can be split among different owners. When the Dueling Dinosaurs fossil was collected, arrangements were made with surface landowners Lige and Mary Ann Murray, but other parties had partial claim to the mineral property. Those individuals—Jerry and Bo Severson—sued, arguing that fossils are minerals and should belong to them. In 2020, the Montana Supreme court ruled that for legal purposes, fossils are “land” and therefore belong to surface landowners. With the sale completed, the next stage in the Dueling Dinosaurs story could begin.

Having already pushed for the acquisition of the fossil, NCMNS Head of Paleontology Lindsay Zanno took charge of the project. Her vision was to create a completely open fossil preparation lab. Rather than being behind glass, the scientists working on the Dueling Dinosaurs would be available for conversation with the public whenever the museum was open. As Zanno explained in an interview, “I conceived the Dueling Dinosaurs project to take the public on a live scientific journey, to illuminate how science works, to show who scientists are and what we look like, and to increase trust in the scientific process.”

To accomplish this, NCMNS hired local firm HH Architecture. They designed the state-of-the-art lab to Zanno’s specifications within the Nature Research Center, the second wing of NCMNS that opened in 2012. The addition also includes two flanking exhibit galleries and street-facing, floor-to-ceiling windows, which allow passerby to see into the lab.

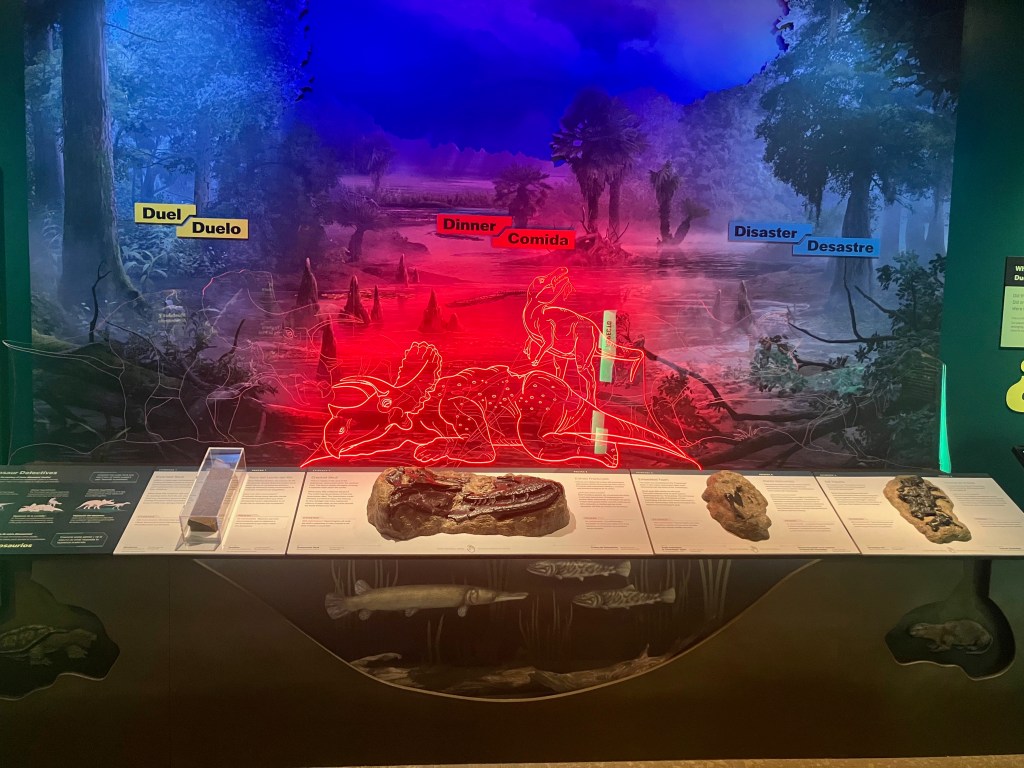

Visitors enter the Dueling Dinosaurs exhibit on the Nature Research Center’s ground floor. The first gallery introduces visitors to the ecosystem of Late Cretaceous Montana. Green panels and walls situate visitors in this verdant environment. After passing small cases with turtle, crocodile, fish, and plant fossils (the purchase of the Dueling Dinosaurs included access to the discovery site, but these are on loan from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science), visitors reach a large display introducing the central mystery of the Dueling Dinosaurs. The exhibit presents three possible scenarios that could have resulted in the dinosaurs being preserved together: duel (a fight to the death), dinner (the tyrannosaur perished while scavenging on Triceratops), or disaster (the animals died separately and were washed together in a flash flood). Color-coded LED outlines of the dinosaurs illustrate the three scenarios in front of an illustrated backdrop.

While these scenarios are presented as being equally plausible, most paleontologists agree that the “disaster” scenario is the likeliest of the three. The real purpose of the exhibit’s presentation is to introduce visitors to the process of stating a hypothesis and finding supporting evidence. Remember, a major part of the rationale behind acquiring the fossil and creating this is exhibit was to show the public what scientists do, and why scientific conclusions are trustworthy. This inquiry-based display attempts to coax visitors through the process of considering the available evidence, and letting it lead them to a conclusion.

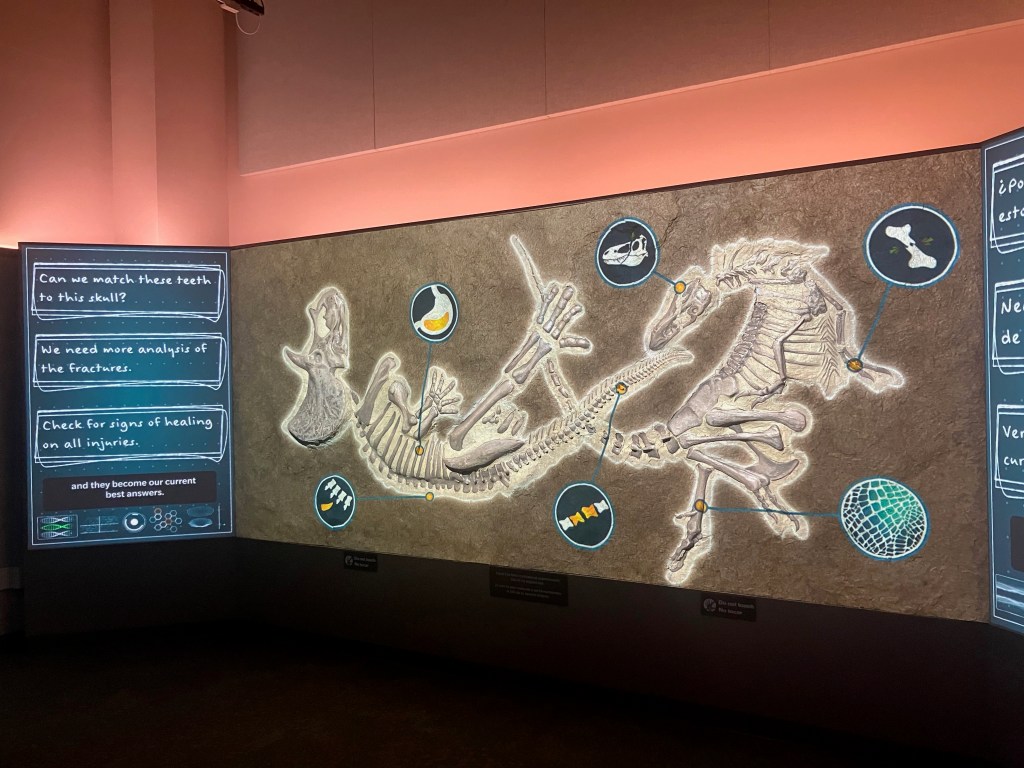

Visitors’ next stop is the lab itself, but traffic is controlled by a roughly 4-minute media presentation at the far end of the first gallery. Relief sculptures of the Dueling Dinosaurs skeletons at 50% scale are the centerpiece of this display. Projected images to the left and right—and on the sculpture itself—illustrate the story of where the fossil came from and what scientists hope to learn from it. Certain moments, like a laser scan across the fossil, suggest at least a little inspiration from the SUE show at the Field Museum. The animated tyrannosaur and Triceratops that appear throughout this and other media pieces in the exhibition were created by Urvogel Games, the people behind the dinosaur simulator game Saurian.

Once inside the lab, nothing but a short plexi barrier separates visitors from the preparators at work. As a former/occasional fossil preparator myself, I can tell you that this space is really, really impressive. It’s not enormous, but it’s big enough to comfortably hold four large jacketed matrix blocks. A 10 ton capacity crane looms overhead, and pneumatic hook-ups for air scribes and dust collectors are within reach throughout the space. I was particularly impressed by a rig that can rotate large jackets on their vertical axis, allowing them to be prepared from multiple directions. No less than seven preparators have been hired to staff this lab, so visitors should find people working all the time. Part of the preparators’ responsibility is to be available to answer questions. Typically, one person is posted by the barrier while the rest of the team works in the background.

The second gallery space is not about the Dueling Dinosaurs specifically, but about the tools and techniques paleontologists use to learn about the past from fossils. The most prominent displays are a cast of Nothronychus (a dinosaur described by Zanno and colleagues) and a nest of oviraptorosaur eggs from Utah. Visitors can touch the tools used by fossil preparators, perform a simulated CT scan of a Thescelosaurus skull, and look through a microscope at growth lines in a sectioned dinosaur bone. I was told this gallery wasn’t quite finished, which might be why it felt unfocused to me. A more prominent header and summative statement at its entrance about the purpose of the gallery might help.

“Science has an accessibility problem,” Zanno said in an interview, “and mistrust in science is rising. We have to bring science out of the back corners and basements…and let our community see who we are and what we do.” The Dueling Dinosaurs exhibition has done exactly that—visitors could not be closer to the process of preparing and studying these fossils without being handed an air scribe. So how is that working out?

I detected a hint of frustration coming from the team members I spoke to. Too many visitors are fundamentally misunderstanding what they are seeing in the lab. They assume the preparators are actors and the fossils are fake, and are often incredulous when told otherwise. The concept that a museum is a place where new science happens is also surprising to a plurality of visitors. One strategy the team has employed is to set up a table of matrix and fragments for the preparator on interpretive duty to sort through. That way, they are clearly working on something when visitors enter and are less likely to be mistaken as an actor or volunteer. Still, if visitors are struggling to recognize real scientists in a real lab when presented with them, the need for access to science in action may be even greater than anticipated.

This might be a “when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail” situation, but I think some reframing of the exhibition and how its presented could go a long way. Right now, the experience is titled “Dueling Dinosaurs,” which is undoubtedly compelling, but elicits its own set of expectations and assumptions about what visitors will see and do. Why not present the experience as what it really is—an opportunity to meet real paleontologists in their place of work? Would it be possible to reverse the order of visitor flow, so they see the gallery about how paleontology is done first, then visit the lab, then finish by learning about the Dueling Dinosaurs as a case study?

Preparing the fossil is expected to take about five years. The goal is to keep the skeletons in their death positions and eventually display them in relief, somewhat like the model in the media presentation. How much matrix to remove is a moving target. The tyrannosaur’s skull has already been CT scanned multiple times with disappointing results. More matrix will need to be cleared to get a good image of the inside of the skull. Meanwhile, extensive skin impressions are preserved across both skeletons, and the team hopes to leave much of this in place. The process is being slowed somewhat by the need to scrape and chip away irreversible glue that was applied by the original preparators.

Aside from determining whether the dinosaurs actually died fighting (don’t count on it), one of the most anticipated answers the project is expected to provide is the identity of the tyrannosaur. When the fossil was at the Black Hills Institute, Pete Larson concluded that it was a Nanotyrannus—a controversial name applied to fossils that many paleontologists think are actually juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex. Indeed, when the fossil was up for auction, it was marketed as a young T. rex, probably for the sake of name recognition. The NCMNS team will eventually weigh in after studying the skeleton more thoroughly.

The lab itself is expected to remain in place once the Dueling Dinosaurs are prepared. The museum already has other very large fossils awaiting preparation.

If you’re able to visit Raleigh, I highly recommend visiting the Dueling Dinosaurs, the open prep lab, and the rest of NCMNS (the museum is free). You can also monitor the preparation process online. Many thanks to Jennifer Anné, Paul Brinkman, Elizabeth Jones, Christian Kammerer, and Eric Lund for speaking to me about the exhibition. Any factual errors are my own.