August 17, 2022. I had just finished a very long drive from Denver to Chicago and wasn’t planning on coming in to the museum that day, but then I heard the news: the fossil was here. The acquisition of the 13th Archaeopteryx by the Field Museum was, by necessity, shrouded in secrecy. There was no reason I needed to know the exact arrival date until the last minute, but I didn’t want to miss the first look at such a historically significant fossil.

That’s how I found myself crammed into the Geology Department’s tiny X-Ray room with a dozen other people. Masks on tight, we all waited with bated breath as Preparator Connie Van Beek pulled up the first images of the slab on the computer. Most of the known Archaeopteryx specimens were commercially prepared before being acquired by museums, but the Field Museum’s new fossil was still sealed in the rock. Aside from the exposed wing feathers—the tell that this was indeed an Archaeopteryx—nobody knew what this block of limestone contained. Would it only preserve the limbs, like the Maxberg and Haarlem specimens, or was there a complete skeleton in there? As we waited for the X-Ray to appear, nobody dared utter the s-word (skull, that is).

Then the image blinked onto the screen. It was a bit faint (these are paper-thin bird bones, after all) but the entire thing was there. Four limbs, a torso, a tail and—folded back in the classic dinosaur death pose—the unmistakable smear of the head and neck. The room erupted into spontaneous applause.

Two years and one month later, the Chicago Archaeopteryx became a permanent resident of Evolving Planet, the Field Museum’s paleontology exhibition. I had the pleasure of serving as the Exhibition Developer for this project, working alongside a brilliant and creative group including Associate Curator Jingmai O’Connor, preparators Akiko Shinya and Connie Van Beek, and all my colleagues in the Exhibitions department. This post is a peek into the thought process behind our new Archaeopteryx display.

Hey, look at me!

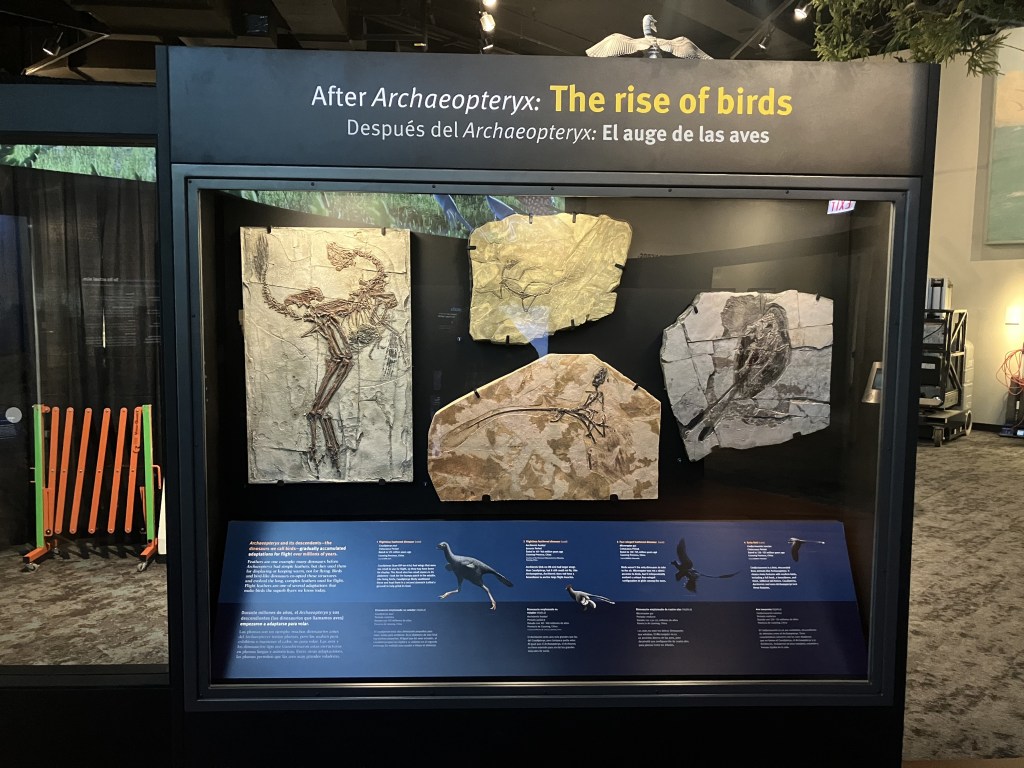

Once it was decided that the Archaeopteryx should be incorporated into Evolving Planet (rather than being displayed somewhere else in the building) the first order of business was figuring out where exactly to put it. Evolving Planet is arranged chronologically—visitors start at the origin of life 4.5 billion years ago and work their way up to the present. Hailing from the Late Jurassic, Archaeopteryx would need to go somewhere in the central dinosaur hall, which covers both the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. But unlike the rest of the exhibition, the dinosaur hall isn’t strictly chronological. There are multiple competing organization schemes in there—the murals on the walls are in Jurassic and Cretaceous clusters, but the central corrals are arranged by evolutionary groups (except when they’re not). And then there’s the big case of marine fossils that span the entire Mesozoic.

I may have lost some sleep over this. Should Archaeopteryx be near the Jurassic Apatosaurus and Stegosaurus (even though it lived on the other side of the world), or near the other theropod dinosaurs? Or maybe it should be with the marine fossils, since it was found in marine limestone. Ultimately, I realized that there was no perfect way to introduce a substantial new display into a space that had already been renovated multiple times, but it wouldn’t ruin visitors’ experience if Archaeopteryx didn’t fit seamlessly into the established flow.

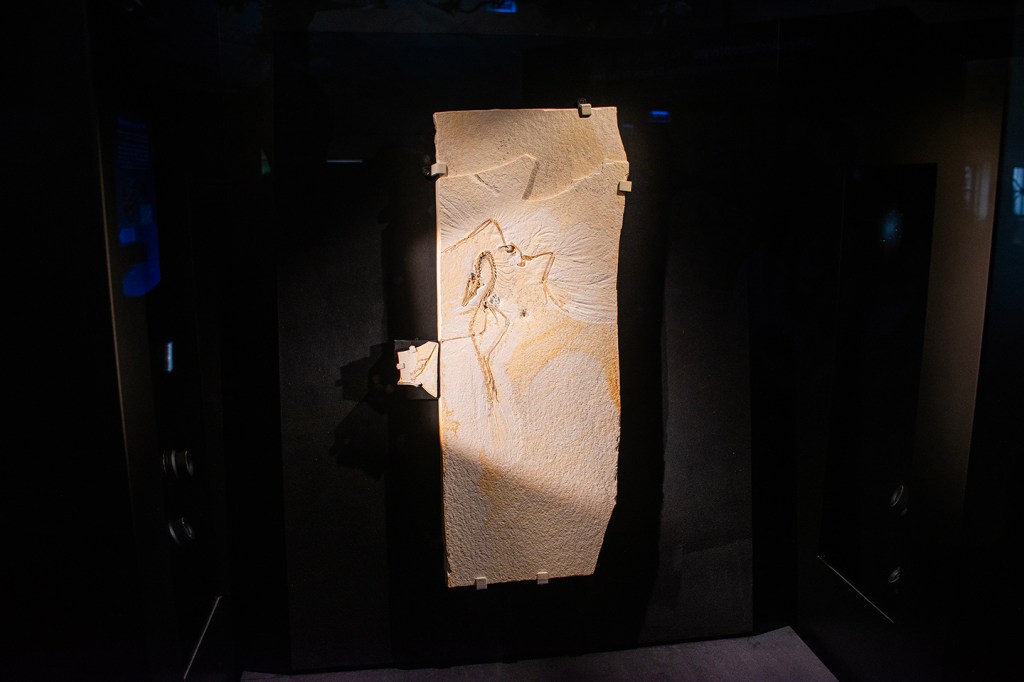

There was a more pressing issue influencing where to place Archaeopteryx: the fossil itself is really small. The bird, now splayed across an 18-inch flat slab, is no larger than a pigeon. It may be the most complete Mesozoic dinosaur in the Field Museum’s collection and a contender for the best-preserved Archaeopteryx yet found, but its size makes it easy to overlook alongside a half dozen giant skeletons. When Senior Designer Eric Manabat and I first met to discuss the new project, we immediately agreed that the display would need a physical presence comparable to the other dinosaurs.

With that in mind, we decided the best place for Archaeopteryx was the largest open space in the dinosaur hall. That way, we could maximize the amount of interpretive content surrounding the fossil, and also create displays that would signal to visitors that this was something worth paying attention to.

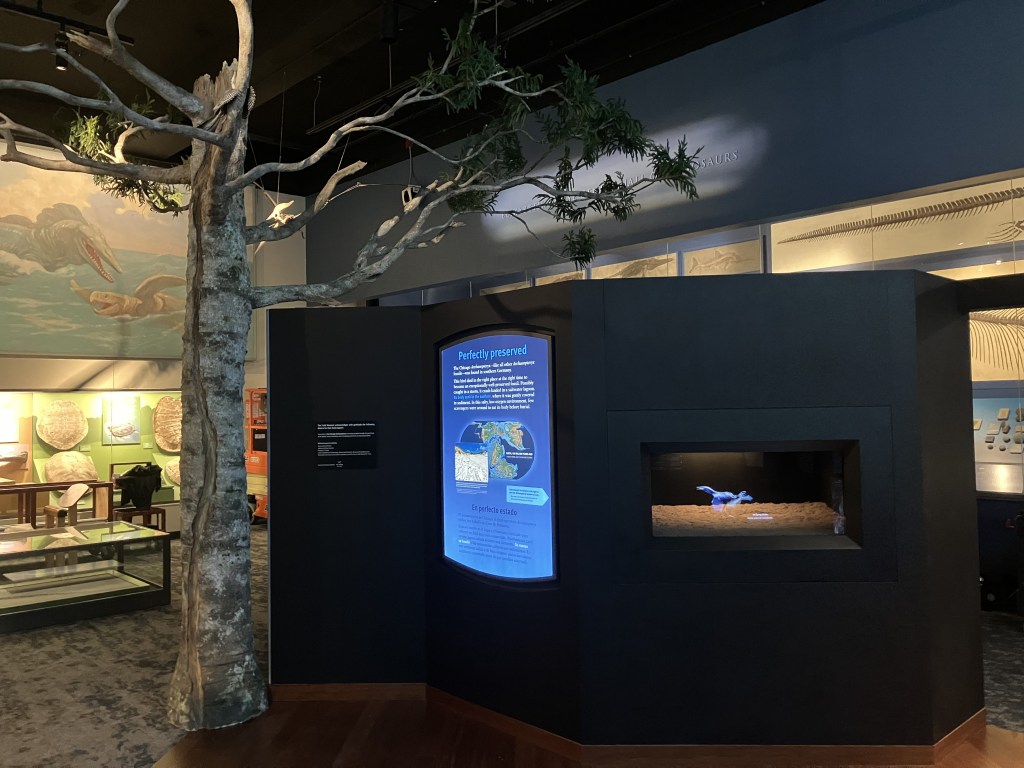

As designed, the Archaeopteryx display has two layers of interpretation. The outer ring, visible from anywhere in the dinosaur hall, showcases the world the first bird lived in. A physical Brachyphyllum tree full of Archaeopteryx models stands in the foreground, and an animated backdrop fills in the rest of the Solnhofen habitat (please notice the coniferous branches peeking into the corners of the animation, which are meant to be an extension of the model tree). We used the habitat reconstruction as the “attractor” because visitors frequently cite these immersive recreations as their favorite parts of our paleontology exhibits.

Once visitors enter the exhibit space, the focus changes to Archaeopteryx itself: how it died and was preserved, how it fits into our understanding of dinosaur evolution, and what’s special about this particular fossil. We wanted to create an enclosed, intimate space so visitors could get up close to the fossil and admire it’s delicate details. A program of changing lights helps direct attention to features like feathers, teeth, and claws. And for visitors who prefer a tactile experience, we have a touchable copy of the fossil at three times actual size.

Recreating the World

Much like the permanent and traveling SUE exhibitions, a new reconstruction of the star dinosaur was a major part of the Archaeopteryx project. This time, we worked with the animation studio PaleoVisLab to create the definitive Archaeopteryx and a world for it to inhabit. I joined Jingmai O’Connor, Latoya Flowers, Wesley Lethem, and others in weekly meetings with paleontologist Jing Lu and animation lead Heming Zhang for nearly a year as they brought the first bird to life.

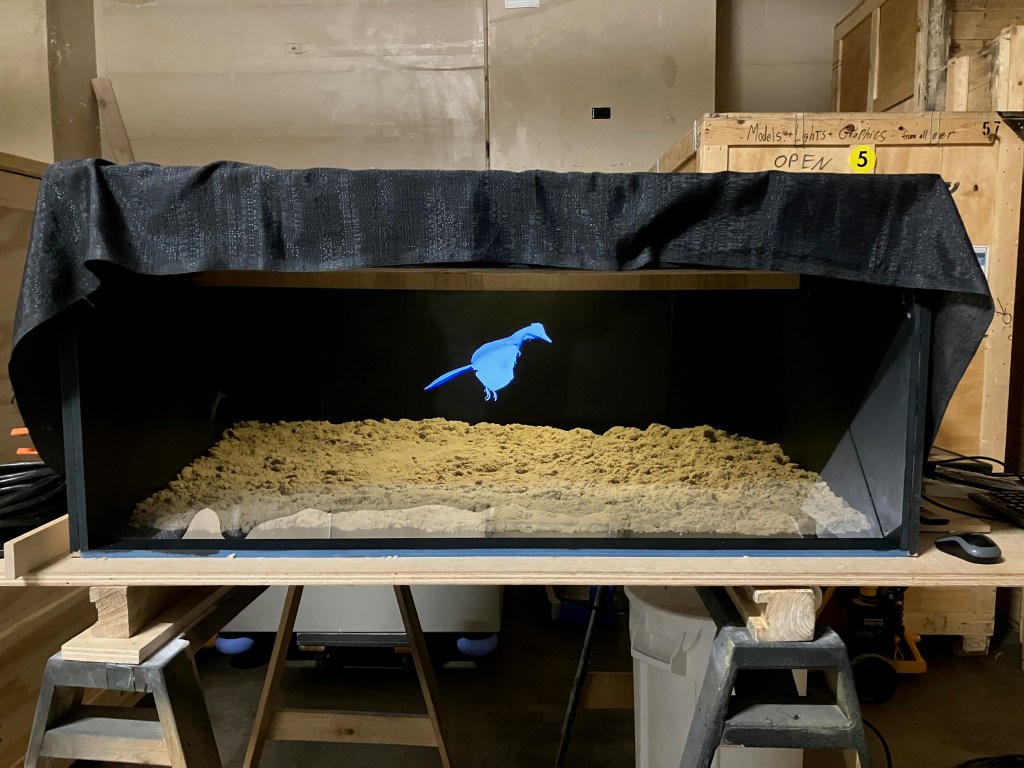

The PaleoVisLab team actually created two animations. The first is a simulated “hologram” which illustrates the taphonomic circumstances that resulted in such a perfectly preserved fossil. This animation resides in a pepper’s ghost chamber, designed and built by Latoya and Wesley. It was fun integrating a 160 year-old magic trick into our exhibit, and I appreciate the cosmic coincidence that the pepper’s ghost technique was first popularized within a few years of the discovery of the first Archaeopteryx.

The second, far more daunting animation was the moving mural. We knew we wanted a big, impressive recreation of Archaeopteryx in its world, but we fretted about how it would fit among the century-old Charles Knight murals that adorn the walls of the dinosaur hall. We wanted something that looked dynamic and modern, but it needed to coexist respectfully with the classic oil paintings, and not attempt to overshadow them. I think we managed to toe the line, and the completed piece even has a few nods to Knight’s Solnhofen scene (which is still on display). The pair of Compsognathus in the lower left corner is the most obvious example.

Heming could not be restrained from from putting astonishing (one might say insane) amounts of detail into every animal and plant in the scene. I particularly remember the day he turned up for the weekly call and enthusiastically showed us that he had modeled both male and female dragonflies, with hundreds of individual lenses on their compound eyes and even different genitalia. Every creature—from the tiny Homoeosaurus scurrying across the sand to the Aspidorhynchus that jumps out of the water for less than two seconds—was carefully reconstructed from the skeleton up. Naturally, the Archaeopteryx got the most attention. Our model is specifically based on new information gleaned from the Chicago specimen—note the shape of the head in particular.

The physical bird models in and around the tree are 3-D prints of the digital version, which was a new approach for us. This solved a problem we had on the SUE project, where we had different artists simultaneously creating images in different media that somehow had to match. But the 3-D prints also created new challenges: the spindly legs and toes were too fragile to actually hold the model’s weight, so we had to come up with some creative ways to mount them in the tree. Janice Lim constructed the mounts and painted the models so that they perfectly match their animated counterparts. And while I’m shouting out artists, illustrations by Ville Sinkkonen, Gabriel Ugueto, Liam Elward, and Scott Hartman also appear in the exhibit.

For me at least, the primary goal of the Archaeopteryx display was to get as many visitors excited about this rare fossil as possible. Given that it doesn’t have the size, name recognition, or ferocious appearance of T. rex or Spinosaurus, getting people to pay attention to a little bird with a hard-to-pronounce name wasn’t a sure thing. The solution was to create as many “entry points” as possible. Maybe you’re interested in animals and how they behave. Maybe you’re interested in history, and how our scientific understanding of the world came to be. Maybe your curiosity is activated by seeing something in motion, or by touching things, or by encountering something unique and special. My hope is that whatever interests you bring with you, we’ve created a space where there’s something for you to get excited about.