Read about the Cretaceous Marsh Dinosaurs, or start the Extinct Monsters series from the beginning.

During the first decade of the 20th century, the United States National Museum paleontology department was located in an offsite building in northwest Washington, DC. It was here that preparators Charles Gilmore, Norman Boss, and James Gidley slowly but surely worked through the literal trainloads of fossil specimens O.C. Marsh had acquired for the United States Geological Survey. The Marsh Collection included unknown thousands of specimens, many of them holotypes, and there was no shortage of gorgeous display-caliber material. Even after the “condemnation of worthless material” Gilmore and his team quickly filled the available exhibit space in the Arts and Industries Building with mounted skeletons.

The Ceratosaurus

With no more display space and plenty more fossils, it was fortunate that the USNM moved to a new, larger building in 1910. In this iconic, green-domed building, the paleontology department received newly furnished collections spaces and the entire east wing to fill with display specimens. The evocatively titled Hall of Extinct Monsters provided a new home for the mounted skeletons already constructed for the old exhibit, as well as plenty of room for new displays.

The Ceratosaurus nasicornis holotype, mounted in relief, was a new introduction to the Hall of Extinct Monsters. Source

The delicate arms of Ceratosaurus were removed several years prior to the hall’s 2014 closing. Photo by the author.

One of the first new additions was the type specimen of Ceratosaurus nasicornis (USNM 4735), mounted in relief. Marshall Felch and Benjamin Mudge collected this specimen in 1883 at the Garden Park quarry near Cañon City, Colorado. The nearly complete skeleton received a cursory description from Marsh upon its discovery, but it was Gilmore who described it properly in 1920. At the time, this was the only Ceratosaurus specimen yet found, making the mount a Smithsonian exclusive. As modern-day preparator Steve Jabo discovered in 2014, Gilmore, Boss, and their colleagues never completely freed the Ceratosaurus from the sandstone it was found in. Once the fossils were taken off display, Jabo spent more than a year finishing what his predecessors started, exposing parts of the skeleton that had never been seen before.

Even today, Ceratosaurus is only known from a handful of specimens. For this reason, the original fossils will not be returning when the current renovation is completed in 2019. The specimen is now in the museums collections, available for proper study for the first time in a century.

In one of the more dramatic scenes in the Deep Time hall, Ceratosaurus is on the losing end of a fight with Stegosaurus. Image copyright NMNH, via twitter.

The new Deep Time hall instead features a three-dimensional cast of the skeleton. Unlike most of the mounted skeletons being prepared for the new exhibition, the Ceratosaurus cast was created entirely in-house. In keeping with the overall goal to imbue the mounts with dynamism, Ceratosaurus is upside-down, kicking frantically while pinned down by a Stegosaurus it shouldn’t have picked a fight with.

The Stegosaurus

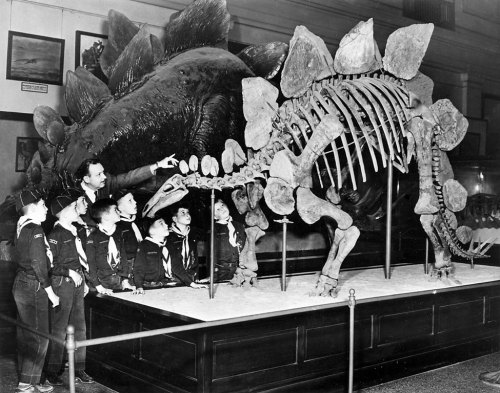

The Smithsonian’s first Stegosaurus exhibit was a life-sized model built for the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. This model found its way into the Hall of Extinct Monsters in 1911. It was joined in 1913 by a mounted skeleton assembled from disarticulated material collected at Garden Park. A third Stegosaurus, the holotype of S. stenops, was introduced in 1918. Lovingly called the “roadkill” Stegosaurus, USNM 4934 is remarkable in part because it was found completely articulated. In fact, before its 1886 discovery by Marshall Felch, it was unknown exactly how the animal’s plates were positioned on its back.

Stegosaurus fossil mount and life-size model circa 1913. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

All three Stegosaurus displays stayed on exhibit through the 1963 and 1981 renovations. Just like the Triceratops and Camptosaurus, time took its toll on the standing Stegosaurus, so in 2003 the fossils were removed from the exhibit. Dismantling the Stegosaurus was particularly challenging because of the large amount of plaster applied by the mount’s creators. In some cases the plaster infill had to be removed with hand tools, which put further pressure on the fossils. Additionally, the rod supporting the backbone had been threaded right through each of the vertebrae, and was extremely difficult to remove. An updated cast was returned to the exhibit in 2004.

In the 1981 exhibit, the roadkill Stegosaurus was displayed alongside brushes and picks to simulate a dig in progress. Photo by the author.

After the halls closed for renovation in 2014, NMNH donated the 2004 Stegosaurus cast to the Virginia Museum of Natural History, a Smithsonian affiliate. The World’s Fair model, meanwhile, now resides at the Museum of the Earth in Ithaca, New York. The roadkill Stegosaurus features prominently in the new National Fossil Hall, mounted upright on the wall by the exhibit’s secondary entrance. A new standing Stegosaurus cast is poised triumphantly over the aforementioned Ceratosaurus. The new cast also corrects problems with how the shoulder girdle was mounted on the previous version.

Stegosaurus mk. 3 is ready for installation. Source

The Camptosaurus

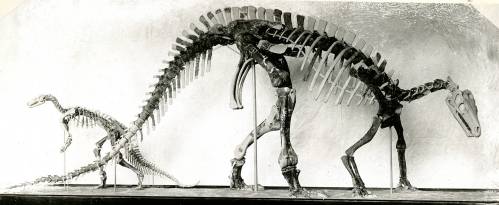

In 1912, two mounted skeletons of Camptosaurus, one large (USNM 4282) and one small (USNM 2210), were introduced to the Hall of Extinct Monsters. William Read excavated both specimens at Quarry 13 in the Como region of Wyoming a quarter of a century earlier. As the first-ever mounted skeletons of Camptosaurus, these specimens have had a rather complex taxonomical history. Marsh initially described both specimens as Camptosaurus nanus, a new species within the genus Camptosaurus (the type species was Camptosaurus dispar, also coined by Marsh). After the fossils were acquired by the USNM, Gilmore re-described the larger individual as a new species, Camptosaurus browni. This designation remained until the 1980s, when Peter Galton and H.P. Powell determined that C. nanus and C. browni were actually both growth stages of C. dispar.

Regardless of what they are called, both specimens were remarkably well-preserved and reasonably complete. Most of the skeletal elements of the larger Camptosaurus came from a single individual that was found articulated in situ. However, some of the cervical vertebrae came from another specimen from the same quarry, and the skull, pubis, and some of the ribs were reconstructed. Of particular interest is the ilium, which has been punctured all the way through by a force delivered from above. Gilmore postulated that “the position of the wounds suggest…that this individual was a female who might have received the injuries during copulation.” The smaller Camptosaurus was also found mostly complete, but two metatarsals came from a different individual and the skull and left forelimb were sculpted.

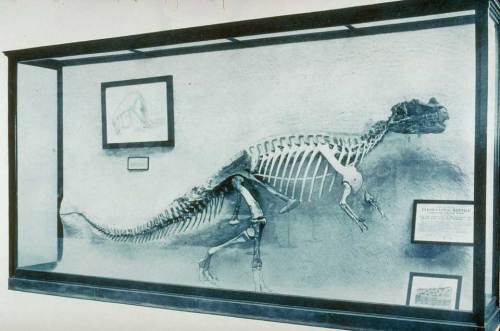

The Camptosaurus mounts as assembled by Gilmore and Boss. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Gilmore supervised the creation of both mounts, and constructed the larger individual himself. Norman Boss took the lead on the smaller specimen. Gilmore aimed to correct many specifics of Marsh’s original illustrated reconstruction of Camptosaurus. To start, he shortened the presacral region to make a more compact torso. Marsh had also inexplicably illustrated Camptosaurus with lumbar vertebrae (a characteristic exclusive to mammals), which Gilmore corrected. Finally, Marsh had reconstructed the animal as an obligate biped, but Gilmore determined that “Camptosaurus used the quadrupedal mode of progression more frequently than any other known member of Ornithopoda.” Accordingly, the larger Camptosaurus mount was posed on all fours. The completed Camptosaurus mounts were placed together in a freestanding glass case toward the rear of the Hall of Extinct Monsters.

Both Camptosaurus skeletons were taken off exhibit in 2008. The delicate fossils, which had suffered from considerable wear and tear over the past hundred years, were stabilized and stored individually for their protection. A new cast of the adult was introduced in 2010, featuring a number of upgrades that reflect our improved understanding of dinosaur anatomy. The arms are closer together and the palms face inward, because the pronated (palms down) hands on Gilmore’s version would not have been possible. The new mount also features a completely different skull. The rectangular model skull used on the original mount was based on Iguanodon, but new discoveries show that the skull of Camptosaurus was more triangular in shape.

The adult and juvenile Camptosaurus were re-prepared, casted, and reassembled by NMNH’s crew of volunteer preparators. Photo by the author.

In the new National Fossil Hall, the 2010 cast returns with a new paint job but no substantial changes. The juvenile Camptosaurus has also returned in cast form.

The Allosaurus

Built in 1981, the Allosaurus fragilis (USNM 4734) was the last Marsh Collection dinosaur to be mounted, although bits and pieces have been on display at NMNH since 1920. There has been considerable interest in this individual recently, in part because Kenneth Carpenter and Gregory Paul proposed in 2010 that it become the neotype for Allosaurus – more on that in a moment. Others are interested in this specimen because of its unique pathologies. In addition to several broken and healed bones, the Allosaurus has a massive puncture wound on its left scapula, which nicely matches the diameter of a Stegosaurus tail spike.

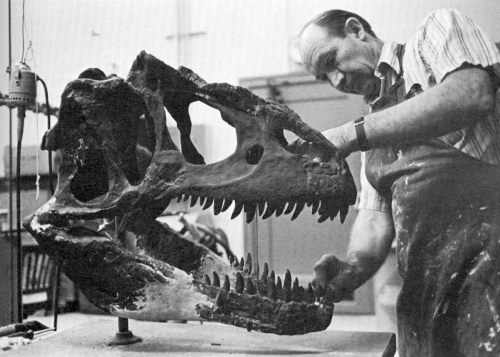

Benjamin Mudge collected this specimen at Garden Park (the same site as the Ceratosaurus) in 1877. Although the Smithsonian obtained the Allosaurus with the rest of the Marsh Collection around 1900, Gilmore did not look at it until at least 1911. All told, USNM 4734 consists of a partial skull and jaw, a complete set of presacral and sacral vertebrae, a few ribs, a pelvis, and virtually complete arms and legs. It would have had a tail as well, but Mudge’s crew accidentally tossed the articulated tail over a cliff while excavating the skeleton. Norman Boss assembled a reconstructed skull, which was displayed through the 1970s. The articulated legs and feet were exhibited in a free-standing case until the late 1950s.

This specimen’s taxonomic history merits some discussion. The holotype Marsh selected when naming Allosaurus (YPM 1930) is notoriously poor, consisting of a single phalanx, two dorsal centra, and a tooth. Dozens of very complete skeletons attributed to Allosaurus are now known, and most specialists basically agree on what an Allosaurus is, but the lack of a usable type with which to define the taxon has been an ongoing problem.

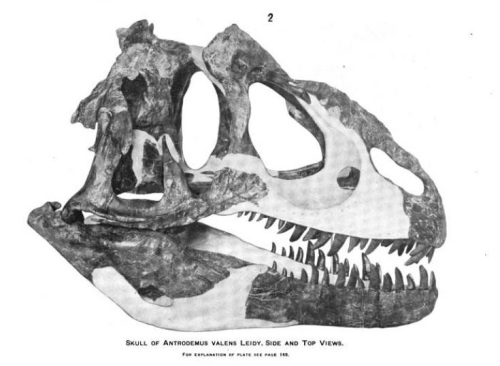

The far more complete USNM 4734 was recovered from the same quarry as the Allosaurus holotype, during the same 1877 field season. Marsh himself actually used this specimen, rather than his designated type, to illustrate subsequent publications on Allosaurus. In 1920, Gilmore flirted with the idea of nominating USNM 4734 as a neotype for Allosaurus, but for reasons that I find difficult to follow, he decided to lump both specimens into the older name Antrodemus valens. Joseph Leidy coined Antrodemus in 1870 based on a single caudal vertebra with no geologic provenance, so this move did little to fix the underlying issue. Nevertheless, Antrodemus remained a popular synonym for Allosaurus in some circles for several decades.

When the NMNH fossil halls were renovated in 1981, the designers noticed that the exhibit badly needed a large theropod mount. Arnold Lewis was tapped to design and construct a complete mounted version of USNM 4734, with some assistance from Ken Carpenter. The tail was cast from a Brigham Young University specimen, but Lewis sculpted the belly ribs and sternum using an alligator skeleton as reference. The completed Allosaurus measures 17 feet from its grinning jaws to the tip of its tail, and a form-hugging armature makes it look particularly dynamic. This mount has been a favorite among visitors for more than 30 years, although the 2001 addition of a Stan the Tyrannosaurus cast has somewhat overshadowed the smaller theropod.

Technicians from Research Casting International took down the Allosaurus in the summer of 2014 as part of the current round of renovations. The skeleton is being remounted (crouching beside a nest mound), but Smithsonian researchers want to get a good look at it before that happens. In particular, curator Matt Carrano has been wondering for some time whether a partial jaw Marsh named “Labrosaurus ferox” actually belongs to this specimen. The “Labrosaurus” jaw, which has an unusual pathology caused by a bite or twisting force, came from the same quarry as USNM 4734, and appears to be the same portion of jaw that the more complete skeleton is missing. Time will tell whether Carrano’s hunch is correct. Meanwhile, Carpenter and Paul’s petition to replace the Allosaurus type with this more complete specimen from the same locality is still pending.

The Marsh dinosaurs have been of critical importance in our understanding of the Mesozoic world, but at this point these fossils are historic artifacts as well. When they were uncovered, the American civil war was still a recent memory, and railroads had only recently extended to the western United States. Before the first world war they had been assembled into mounts, and for more than a century these fossils have been mesmerizing and inspiring millions of visitors. Several of these mounts, including the Triceratops, Ceratosaurus and Camptosaurus, were the first reconstructions of these species to ever appear in the public realm, and therefore defined popular interpretations that have lasted for generations. Some visitors may lament that domr of the original specimens have been replaced with replicas, but the fact is that these are irreplaceable and invaluable national treasures. They inform us of our culture, and our dedication to expanding knowledge and our rich natural history. We only get one chance with these fossils, and that is why the absolute best care must be taken to preserve them for future generations.

References

Carpenter, K., Madsen, J.H., and Lewis, L. 1994. Mounting of Fossil Vertebrate Skeletons. Vertebrate Paleontological Techniques. 285-322.

Fox, A. 2018. A Smithsonian Dino-Celebrity Finally Tells All. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-of-natural-history/2018/10/16/smithsonian-dino-celebrity-finally-tells-all

Gilmore, C.W. 1912. The Mounted Skeletons of Camptosaurus in the United States National Musuem. Proceedings of the US National Museum 14:1878.

Gilmore, C.W. 1920. Osteology of the Carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum with Special Reference to the Genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus. United States National Museum Bulletin 110:1-154.

Gilmore, C.W. 1941 A History of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology in the United States National Museum. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 90.

Jabo, S. 2012. Personal communication.

Lee, J.J. 2014. The Smithsonian Disassembles its Dinosaurs. National Geographic Online. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/07/140731-dinosaur-hall-smithsonian-renovation-culture-science/

Paul, G.S. and Carpenter, K. 2010. Allosaurus Marsh, 1877 (Dinosauria, Theropoda): proposed conservation of usage by designation of a neotype for its type species Allosaurus fragilis Marsh, 1877. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 67:1:53-56.

Thomson, P. 1985. Auks, Rocks, and the Odd Dinosaur: Inside Stories from the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Thomas Y. Crowell.