In Laurel, Maryland, a trail of banners depicting a herd of the sauropod dinosaur Astrodon johnstoni leads the way to Dinosaur Park, the site of a historically significant fossil deposit. At the Maryland Science Center in Baltimore, a life-sized Astrodon sculpture towers over the “Dinosaur Mysteries” exhibit. And since 1998, Astrodon has been the official state dinosaur of Maryland, joining other state symbols like the black-eyed susan and Baltimore oriole. In short, Astrodon is a sort of mascot for mid-Atlantic paleontology. Named in 1858 for fossils found in a Prince George’s County iron mine, the appeal of Astrodon for Marylanders is obvious: it’s a home-grown dinosaur in a region that is not widely recognized for its fossil resources, and the story of its discovery also calls attention to the state’s industrial heritage.

But what sort of animal was Astrodon, and how much do paleontologists truly know about it? Compared to many other extinct animals found around the world, the fossil record for Astrodon is and always has been fairly poor. The name Astrodon was first bestowed upon nothing more than isolated teeth, and although other fragmentary remains attributed to Astrodon have been uncovered over the past 150 years, reconstructions of the Maryland sauropod are mostly derived from the fossils of relatives found elsewhere. What’s more, the name Astrodon has a convoluted history, having been applied haphazardly to fossils found across the country and even around the world. For these reasons, some paleontologists would prefer that the name Astrodon not be used at all.

Lacking a scientific consensus on what sort of animal the Maryland sauropod was or even what it should be called, I find myself in a difficult position as an educator. How can the messy and contentious taxonomy of Astrodon be condensed into something teachable? Is simplifying or downplaying this controversy doing our audience a disservice, and to what degree?

The taxonomic history of Astrodon

The first scientifically recognized North American dinosaur fossils were found in the Mid-Atlantic region, a scant 17 years after dinosaurs were first recognized as a biological group in 1842. Joseph Leidy’s Hadrosaurus from the New Jersey coast is credited as the first American dinosaur to be described, but Astrodon was a close second. During the mid-19th century, iron mining was big business in central Maryland. Miners extracted large boulders of siderite, or iron ore, from open pit mines throughout Prince George’s County, and these miners were the first in the region to discover dinosaur bones and teeth. The siderite was being mined from clay deposits now known as the Arundel Formation, part of the larger Potomac Group that extends throughout Maryland (the Potomac Group was laid down during the Early Cretaceous period, between 125 and 113 million years ago). Members of the Maryland Academy of Sciences recognized the fossils from the Arundel clay as similar to the English fossil reptiles that Richard Owen had recently unified as Dinosauria. In 1858, academy member Christopher Johnston published a description of a set of teeth from the iron mines in the American Journal of Dental Science, which he named “Astrodon” (Joseph Leidy turned this informal name into a proper binomial, Astrodon johnstoni, in his 1865 review of North American fossil reptiles).

Today, most paleontologists consider it poor judgment to name a new taxon based only on teeth. When scientists describe a newly discovered organism, they designate a type specimen, which is used to define that taxon in perpetuity. But when the type specimen is especially fragmentary, or only consists of a small part of the organism, it poses a problem for future researchers. In the case of Astrodon, no newly discovered fossils other than teeth can be confidently referred to the same species. In 1858, however, paleontological norms were very different. All dinosaur fossils known at the time were exceedingly incomplete: scientists knew that dinosaurs were reptiles and that they were very big and not much else. Any new fossils, even teeth, represented a major addition to our understanding of the life appearance and diversity of these extinct animals. For modern paleontologists, Johnston’s published description of the Astrodon teeth is vague and uninformative, but in his day, these fossils were distinct from anything else yet known.

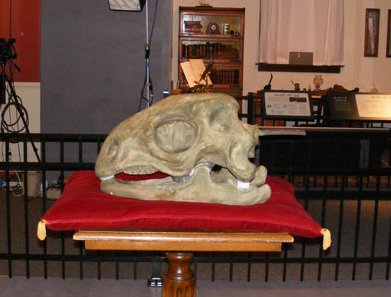

Astrodon teeth are on the lower left.

In December of 1887, famed paleontologist Othneil Charles Marsh sent his best fossil hunter, John Bell Hatcher, to search the area in Prince George’s County where Astrodon was discovered. Judging from Hatcher’s journal entries, he didn’t have a great time. It rained and snowed almost constantly, and on several days his team didn’t bother to show up for work. Although Hatcher managed to find numerous dinosaur, crocodile and turtle fossils, these finds did not match the quality of the fossils Hatcher had been finding in the western states, and no return trips were made. Nevertheless, Marsh saw fit to name two new dinosaur species from the material Hatcher collected: Pluerocoelus altus and Pluerocoelus nanus. Neither taxon was named for material that would be considered diagnostic if found today: P. altus was based on a tibia and fibula, while P. nanus was based on four nonadjacent vertebrae.

By this time, more complete dinosaur fossils from the American west were beginning to reveal a clearer picture of dinosaur diversity. Based on the shape and size of the fossils collected by Hatcher, Marsh determined that they belonged to sauropods, the group of long-necked herbivores that includes Diplodocus and Apatosaurus. More specifically, Marsh recognized that the Arundel sauropods were similar to “Morosaurus” (now called Camarasaurus) from Colorado. Today, the lineage of stocky, broad-nosed sauropods that includes Camarasaurus and its closest relatives are called macronarians. Unfortunately, by modern standards Marsh’s descriptions of P. altus and P. nanus are rudimentary in nature, and no distinguishing characteristics not common to all macronarian sauropods were offered.

Pleurocoelus (or Astrodon?) fossils collected by Hatcher. Image from NMNH online exhibit Backyard Dinosaurs.

Contra Marsh, Hatcher suspected that there was only one sauropod in the Arundel Formation. P. altus and P. nanus were probably growth stages of one species, and the Astrodon teeth, now recognized as typical of macronarians, probably came from the same animal, as well. Since the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature decrees that the first published name given to a taxon has priority, Astrodon would take precedence over Pluerocoelus. Later, Charles Gilmore published a review of the Arundel fossils, in which he concurred with Hatcher that P. altus was a junior synonym of Astrodon, but retained P. nanus as a separate species.

Then things started getting really complicated. While paleontologists were still debating how many sauropod species existed in the Arundel clay, Marsh and others had started naming lots of new species of Pluerocoelus. Fossils found in Texas, Oklahoma and even the U.K. were all thrown into the Pluerocoelus bucket, including P. montanus, P. valdensis, P. becklesii and P. suffosus. For much of the 20th century, Pluerocoelus was a classic wastebasket taxon, into which any and all sauropod fossils from early Cretaceous strata were casually thrown. Since the Pluerocoelus type specimens designated by Marsh were insufficient to define the taxon based on morphology, the name became little more than a temporal marker. Adding to the confusion, researchers continued to disagree over whether all these new Pluerocoelus species should be sunk into the earlier genus Astrodon.

In recent years, some progress has been made toward untangling this mess of early Cretaceous sauropods. There is a general consensus that fossils not found in Maryland’s Potomac Group differ substantially from the Arundel sauropods and should never have been referred to Pluerocoelus or Astrodon. New names have been proposed for the midwestern sauropods, including Astrophocaudia and Paluxysaurus. However, removing the non-Maryland fossils from the discussion merely returns us to the original set of problems: how many sauropods are represented in the Arundel clay, what were they like in life, and what should we call them?

Creating a coherent picture of Astrodon

Unfortunately, the answers to these questions depend on who you ask. The most thorough review of Arundel sauropods from the last decade was published by Kenneth Carpenter and Virginia Tidwell in 2005. Carpenter and Tidwell reaffirmed Hatcher’s conclusion that Pluerocoelus is synonymous with Astrodon, and that as the earliest published name, Astrodon has priority. This decision is apparently based only on the fact that the fossils came from the same stratum, however, since the Astrodon holotype cannot be compared to anything besides other teeth. For this reason, Michael D’Emic proposed in 2012 that the names Astrodon and Pluerocoelus are nomen dubia and should both be dropped entirely. Ultimately, neither solution is practical for identifying the sauropod fossils that continue to be collected from the Arundel Formation. Either we blindly refer any and all sauropod fossils to Astrodon, even though we lack a usable holotype, or we have no label available at all. One solution would be to establish a new type specimen (called a neotype) for Astrodon, but this has yet to be done.

Both camarasaur and brachiosaur-shaped Astrodon reconstructions are reasonable. Artwork by Dmitry Bogdanov, via Wikipedia.

While many more sauropod fossils have been found in the Arundel clay since Hatcher’s 1887 expedition, we do not have enough material to fully elucidate what these animals looked like. Size estimates have varied enormously, from as little as 30 feet to as much as 80 feet in length. The assortment of fossil bones and teeth that have been found tell us we have a macronarian sauropod, and we can reconstruct its general shape based on more completely known relatives. However, macronarians were a fairly diverse bunch, ranging from the comparatively stocky camarasaurs to high-shouldered, elongate brachiosaurs. Carpenter and Tidwell describe the Arundel sauropod fossils, particularly the limb bones, as being fairly slender, but still more robust than those of Brachiosaurus. They do recognize, however, that nearly all known Arundel sauropod fossils come from juveniles, which may vary proportionally from adults. Because the precise affinities of Astrodon are unclear, artistic reconstructions vary substantially. The National Museum of Natural History’s Backyard Dinosaurs exhibit and website shows a camarasaur-shaped sauropod, while the life-sized sculpture at the Maryland Science Center is based on the brachiosaur Giraffatitan. At Dinosaur Park in Laurel, meanwhile, both versions are on display. More fossils, ideally cervical vertebrae or more complete adult material, are needed to clarify what the Arundel sauropod looked really like.

Teaching Astrodon

When I show people the teeth and partial bones attributed to Astrodon during public programs, I am almost always asked, “if that’s all you’ve found, how do you know what the whole animal looked like?” As demonstrated by this post, it takes 1,700 words and counting to give a proper answer, which is too much for all but the most dedicated audiences. Nevertheless, to do anything less is to skip crucial caveats and information. Scientists are choosy about the words they use, filling explanations with “probablys” and “almost certainlys”, but they do so with good reason: when one’s job is to create and communicate knowledge, there is no room for ambiguity about what is and is not known. It is therefore just a bit dishonest to say that a large sauropod called Astrodon that was related to Brachiosaurus lived in Maryland, and yet I do so every week. How can I possibly sleep at night?

I’ll admit it can be difficult, but I get by because using one proviso-free name for the Maryland sauropod seems to be informative and helpful to my audience. I only have people’s attention for so long, and I’d rather not spend that time on tangents about how Astrodon should really be called Pluerocoelus or why my use of either name is imprecise and problematic. I want visitors to walk away understanding how paleontologists assemble clues from sedimentary structures and anatomical comparisons to reconstruct ancient environments and their inhabitants. I’d like for visitors to practice making observations and drawing conclusions, and understand how paleontology is a meticulous science that can be relevant to their lives. “Paleontologists are weirdly obsessed with changing names” is not one of the most important things to know about paleontology.

Taxonomy, the science of naming and identifying living things, is unquestionably valuable. Biologists would be lost without the ability to differentiate among taxa. From my perspective, however, the public face of paleontology tends to overemphasize taxonomic debates in lieu of more informative discussions. There will always be somebody willing to argue whether Tarbosaurus bataar should be sunk into Tyrannosaurus, or to give incorrect explanations for why we lost “Brontosaurus.” In the end, though, these debates have more to do with people’s preferences than the actual biology of these animals. Astrodon may not be a diagnostic taxon in the strictest sense, but we need to call our fossils something, and taxonomic labels exist to be informative and useful. If asked, I’m always happy to provide the full story. But for the time being, Astrodon seems to be working just fine.

References

Carpenter, K. and Tidwell, V. 2005. Reassessment of the Early Cretaceous sauropod Astrodon johnstoni Leidy 1865 (Titanosauriformes). In Carpenter and Tidwell (eds.), Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IA: Indiana University Press.

D’Emic M.D. 2012. Revision of the sauropod dinosaurs of the Lower Cretaceous Trinity Group, southern USA, with the description of a new genus. Journal of Systematic Paleontology, iFirst 2012, 1-20.

Gilmore, C.W. 1921. The fauna of the Arundel Formation of Maryland. Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 59: 581-594.

Kranz, P.M. Dinosaurs in Maryland. 1989. Published by Maryland Geological Survey, Department of Natural Resources, Educational Series No. 6.

Marsh, O.C. 1888. Notice of a New Genus of Sauropoda and Other New Dinosaurs from the Potomac Formation.

Please note that the usual disclaimer applies: views or opinions expressed here are mine, and do not reflect any institution with which I am affiliated.