Old and new taxidermy pieces introduce visitors to their extended family tree. Source

Start with A 21st Century Hall of Mammals – Part 1.

The Kenneth E. Behring Family Hall of Mammals opened at the National Museum of Natural History in November 2003. The hall’s airy, minimalist aesthetic represented a radical departure from traditional wildlife exhibits, shaking off taxidermy’s dusty reputation and utilizing the museum’s mammal collection to tell the story of evolution for modern audiences. As we saw last time, developing such an exhibit was not without controversy—everything from the source of funding to the ethics of demolishing historic dioramas came under intense scrutiny. In this post, we’ll explore the work that went into building the exhibit, and how the team’s bold vision eventually paid off.

Building the Animals

The Hall of Mammals cost $31 million and involved over 300 people. However, the job of constructing or updating the 274 taxidermy mounts was largely done by three individuals. John Matthews and Paul Rhymer were the Smithsonian’s last full-time taxidermy specialists. Rhymer in particular was a 3rd generation legacy—his grandfather had worked on the now-dismantled dioramas in the old mammal halls. The newcomer was Ken Walker, an award-winning taxidermist who moved to Washington from Alberta to work on the exhibit.

Beasts take shape in a massive workshop just outside the beltway.

Matthews, Rhymer, and Walker set up shop in a 50,000-square-foot studio in northern Virginia. As museum taxidermists, they took no shortcuts in making the animals they built look right. The process for a creating a given mount would start with hours of research, using photos and videos to get a sense of the animal being recreated. The goal is to get inside the creature’s head, to understand how it thinks, moves, and behaves. Next, the artist builds a clay sculpture, either from scratch or using a commercial mannequin as a starting point. It is at this stage that the pose and attitude are set, and the bulge of every bone and muscle must be perfect. Only then can the tanned skins be stitched onto the sculpture and final adjustments be made. A single animal can take 100 hours or more to create.

Making the animals for the Hall of Mammals was particularly challenging because the designers called for so many dramatic and unusual behaviors. These animals aren’t just standing around—the gerenuk is stretching to full height in order to browse from a tree, the bobcat is leaping to catch a bird in mid flight, and the giraffe is spreading its forelimbs and bending down to drink. Cutaways reveal an anteater’s tongue snaking into an insect nest and a blackfooted ferret interloping in a prairie dog burrow. Achieving this level of dynamism with clay, wax, and dead fur is only possible with a top-notch understanding of biomechanics.

This paca scratching itself behind the ear is an example of the expressive and dynamic mounts produced for the Hall of Mammals. Photo by the author.

90% of the featured animals are on display for the first time, and the pelts came from a variety of sources. NMNH sent out a wishlist to museums, zoos, research facilities, and private collectors. A tree kangaroo came from the National Zoo’s offsite research facility in Virginia. The okapi had recently died of old age at Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo. The playpus and koala were imported from Australia, and the leopard, jackal, and Chinese water deer were from Kenneth Behring’s personal collection.

All of the animals came from existing collections—nothing was killed specifically for the new exhibit. Given modern sensibilities and the museum’s conservation-oriented mission, this was a laudable decision. Nevertheless, using old specimens created many new challenges. The tiger and panda that had been at NMNH for over a century had faded fur, which had to be dyed. The orangutan was a lab animal preserved in a vat of alcohol. The fur was usable, but the face and hands were ruined, and had to be reconstructed. Only a male lemur was available, but some clever alterations turned it into a female carrying a baby. The Brookfield zoo okapi had hooves which were overgrown from lack of use. The taxidermists filed them down to make the animal look like its wild counterparts. In many cases, the taxidermists were not merely making dead animals look alive, they were creating imaginary lives that these individuals never actually had.

Creating the Space

While the taxidermists were working 10 to 12 hour days building the animals, yet another team was working on creating the spaces they would inhabit. The animals would be set in minimalist, conceptual environments—a terraced floor suggests a watering hole, and metal poles and plastic tubes stand in for branches and trees. The specimens are presented like sculptures in an art gallery, or perhaps trendy gadgets at a tech showcase.

Visitors explore the Apple Store of taxidermy. Photo by the author.

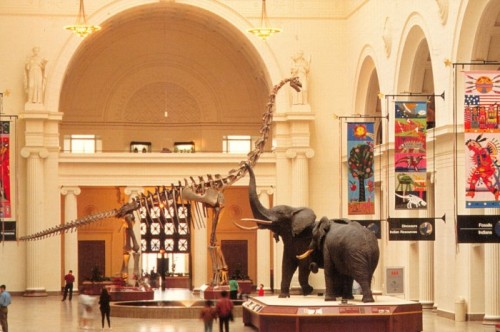

A key aspect of the new hall is the restoration of the west wing’s original Beaux Arts architecture. Designed by the historic Washington architectural firm Hornblower and Marshall, the space was originally a three-story neoclassical chamber with a large skylight and ornate plaster and chrome embellishments. Over the years, false walls had been added to carve the hall into ever smaller spaces to accommodate new exhibits. The original architects may have been on to something, however. NMNH gets upwards of seven million visitors every year, and crowding is a common complaint. To help mitigate this, the Hall of Mammals design team wanted to return to the wide open floor plan, with lots of space for visitor traffic and multiple viewing angles on most specimens. Starting in 1999, Hayes, Seay, Mattern and Mattern spent two years restoring the west wing to its former glory.

Since the new exhibit furnishings couldn’t touch the historic structure of the building, creating the hall was like assembling a building within a building. The designers settled on a steel framework that would visually separate the new exhibits in the center of the hall from the classic architecture. The metal structures double as mounts for the exhibit’s complex lighting systems, and also recall the ribcage of a whale. The choice to display some of the taxidermy pieces in open settings has been a point of contention from a conservation standpoint. The mounts placed in open air, rather than climate controlled cases, can be expected to deteriorate over time. According to Project Manager Sally Love, this was a deliberate trade-off. “We felt it was important to break barriers between the animals and our visitors” said Love, “and the animals not behind glass are ones that we can more readily obtain replacements for.”

The Hall of Mammals uses contrast as a key visual motif – in this case the huge walrus juxtaposed with tiny bats. Photo by the author.

Throughout the hall, the architecture is meant to compliment and support the hall’s interpretive themes. The exhibit drives home the point that mammals are tremendously diverse, but also similar in key ways due to their common ancestry. The entry space, flanked by two-story cases of taxidermy specimens, illustrates that diversity. Contrast is a key visual motif: large animals beside small ones, specimens exhibited high and low, and so on. Height in particular is used to keep visitors looking in all directions. A leopard snoozes on a branch over visitors’ heads, while a platypus in its burrow can only be seen by crouching down. Meanwhile, the perimeter of the hall is devoted to animals that share particular habitats, referencing the impact environmental change has had on mammalian evolution.

Animals of the North American forest. Photo by the author.

Among the most exciting parts of the exhibit is the east African watering hole in the center of the hall. Since the taxidermy mounts are static, the designers filled the space with video screens and dynamic lighting to keep the scene in motion. Footage of animals in motion cycles on rear-projected frosted-glass panels behind the mounts, while screens set in the floor show footprints and evidence of changing seasons. Suzanne Powaduik designed the immersive light effects, which repeat every ten minutes. The highlight is a thunderstorm heralding the arrival of the rainy season, accomplished with sound effects and a xenon flasher. Director of Exhibits Stephen Petri explains how the special effects tie in with the exhibit’s narrative: “evolution occurs over long periods of time but is a response to changes that happen moment to moment.”

Legacy

The completed Hall of Mammals occupies 25,000 square feet, minus about 3,000 annexed by a gift shop and special exhibit space. It contains 274 taxidermy specimens, 12 fossil replicas, and numerous sculptures and interactives. The hall is the culmination of five years of work – a long time to be sure, but a breakneck pace compared to the 25 years it took to complete the classic Akeley Hall of African Mammals at AMNH. It was also one of the biggest taxidermy projects attempted in the past 80 years, and for at least a little while, it made Matthews, Rhymer, Walker, and their peculiar trade into stars.

Although the animals themselves are motionless, light, sound, and video fill the space around them with life. Source

The Hall of Mammals received at least nine industry awards, and has become a benchmark for exhibits in development today. Teachers have also praised the exhibit – writer Sharon Berry’s text is pitched for families, and written with National Science Foundation Life Science Standards in mind. While the exhibit has showy special effects and some playground-like elements, the meaning and message is omnipresent.

While historic wildlife dioramas are incredible works of art and science, they are absolutely of another time. Indeed, a major part of their appeal is that they are a look into the past, to an era when naturalists believed ecosystems could be summed up in a window box. For all their meticulous detail, dioramas have never been able to truly recreate nature. They are uncanny reflections of nature, filtered through the worldview of their creators. Dioramas have great cultural and intellectual value, and it is a tragedy whenever one of these irreplaceable time capsules is lost. At the same time, though, NMNH should be commended for stepping outside the box (so to speak). The Hall of Mammals does not attempt to replicate the experience of viewing living wildlife – it showcases the diversity of nature in a way that only a museum can. It’s gorgeous, engaging, informative…and it’s a beast all its own.

References

Liao, A. 2003. Natural history exhibits venture beyond black-box dioramas. Architectural Record 11:04:275279.

Milgrom, M. 2010. Still Life: Adventures in Taxidermy. New York, NY: Mariner Books.

National Park Service. 2004. Mammal Hall Study Report: Evaluation by National Park Service Media Specialists of New Exhibits at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Dc. https://www.nps.gov/hfc/pdf/imi/si-mammal-hall-report.pdf

Parrish, M. and Griswold, B. 2004. March 2004 Meeting Report: Mammals on Parade. Guild of Natural Science Illustrators. http://www.gnsi.science-art.com/GNSIDC/reports/2004Mar/mar2004.html

Polliquin, R. 2012. The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania University Press.

Trescott, J. 2003. Look Alive! The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/2003/07/14/look-alive/d1944407-ffbb-4e1f-8e06-06cd9ddec57d