Paleoartist Tyler Keillor has not one but two new tyrannosaur sculptures on display in museums north of Chicago, and this past weekend I paid both of them a visit. Keillor has been reconstructing extinct animals since 2001, most frequently in collaboration with Paul Sereno. You may well have seen Keillor’s fleshed models of Rugops, Kaprosuchus, Eodromaeus, and others, all commissioned by Sereno to accompany press releases announcing new discoveries. Keillor also specializes in restoring incomplete fossil material, assembling physical or digital models of the complete, undamaged bones. The composite Spinosaurus skeleton from the 2014 National Geographic traveling exhibit was his work, as is the skull on the mounted skeleton of Jane the juvenile Tyrannosaurus at the Burpee Museum of Natural History.

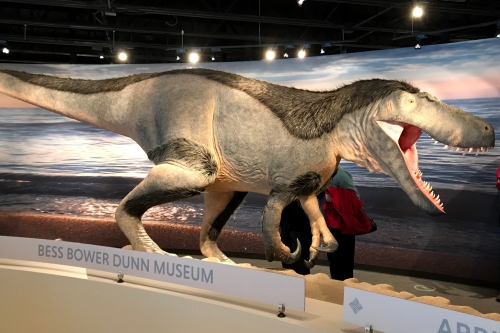

One of Keillor’s latest and most ambitious pieces debuted on March 24th at the brand-new Bess Bower Dunn Museum in Libertyville, Illinois. Standing at the entrance to the museum’s galleries, the life-sized Dryptosaurus is a show-stopping centerpiece. Never mind that no dinosaur fossils have been found in Illinois – Dryptosaurus lived on the other side of the Cretaceous continent of Appalachia, which is as good an excuse as any to include a giant model dinosaur.

During the very well-attended opening event, Keillor gave a standing-room-only talk about creating the model. Dryptosaurus is only known from a handful of fossils, the most complete parts being the arm and leg. Working with Richard Kissel, who served as the project’s scientific advisor, Keillor had to make a number of educated choices to turn the available fossil material into a 20-foot fleshed model. The shape of the head, for example, is based on that of Jane, while the tiny, millimeter-sized scales are informed by recently published skin impressions of various tyrannosaurs. Less certain is the choice to give Dryptosaurus a two-fingered hand. For the time being, the three-fingered skeletons Research Casting International built for the New Jersey State Museum are no less reasonable.

Opening day at the Dunn Museum was mobbed – it’s great to see so many people excited about a new museum!

Keillor’s 2009 Dryptosaurus head is meant to be a male, while the new sculpture represents a female.

During the planning stages, Keillor prepared three possible poses for the museum to pick from. The Dryptosaurus could be standing tall, leaning forward with its mouth open, or crouching down next to a nest mound. Keillor favored the nesting pose, both because it was unusual and because the Dryptosaurus holotype fossils may have come from an animal that had recently laid eggs*. Unsurprisingly, museum staff opted for the more spectacular open-mouthed version.

The bulk of the model is foam, created on a milling machine using data from a digital model produced by Keillor. The foam body form is covered with nearly 200 pounds of epoxy putty, applied and textured by hand. Keillor casted the head as a separate piece, using the molds from a standalone Dryptosaurus head he produced for the Dunn Museum’s predecessor in 2009. The patches of fluff are made from a commercially-available synthetic fiber that resembles kiwi feathers.

*Edward Cope noted in the 1880s that the Dryptosaurus limb bones had large, hollow medullary cavities. Gravid female birds grow extra layers of bone in their medullary cavities to stockpile calcium, which they use to produce eggshells. We now know that several non-avian dinosaur species did the same.

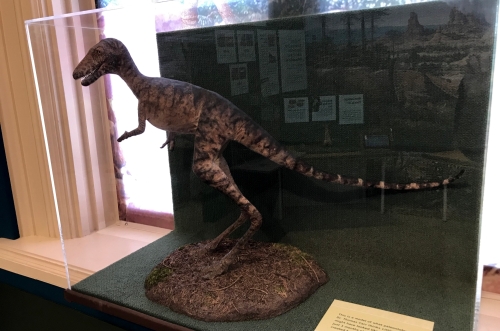

Keillor’s other new model is “Little Clint” the infant Tyrannosaurus rex, which debuted at the Dinosaur Discovery Museum in Kenosha, Wisconsin with absolutely no fanfare. The model is part of a new exhibit all about the discovery and interpretation of the pocket-sized T. rex fossils it’s based on. Frustratingly, there’s no mention of the exhibit on the museum’s website, and I would have never known about it if Keillor hadn’t mentioned it (I’m sure it’s not the museum’s fault, I too have known the joys of working within the constraints of a large municipal website). The model is roughly two and a half feet long, and is almost grotesque in its spindly proportions. Judging by photos accompanying the model, Keillor used a traditional build-up process, rather than the physical-digital hybrid techniques employed in the making of the Dryptosaurus.

Dryptosaurus and Tyrannosaurus both belong to the same group of theropod dinosaurs (tyrannosaurs), but in creating the two models Keillor went in two very different directions when reconstructing their soft tissues. Working with Richard Kissel of the Yale Peabody Museum, Keillor gave Dryptosaurus a patchy coat of shaggy integument, as well as fleshy lips that would easily cover the animal’s teeth if it were to ever close its mouth. However, Carthage College’s Thomas Carr, scientific advisor for Little Clint, requested a scaly hide with a crocodilian tooth-exposing grin.

It turns out feathers and lips on large theropods (and tyrannosaurs in particular) are fairly contentious subjects, at least among the sort of people who like to argue about these things on the internet. It is well-established that feathery integument was widespread among theropods, and even certain other dinosaurs. Several members of the tyrannosaur family have been found with fossilized fuzz impressions, including the Dryptosaurus-sized Yutyrannus. This means it’s reasonable to expect that all tyrannosaurs, including Tyrannosaurus rex, were feathered to some degree. However, a recent publication by Phil Bell and colleagues suggests the opposite: an assortment of small skin impressions from Tyrannosaurus and its closest relatives reveal only scaly skin. Meanwhile, ongoing research by Robert Reisz demonstrates that theropods had fleshy lips, but this is contradicted by Carr’s own findings that some tyrannosaurs had armored scales on their maxillary margins.

So which interpretation of tyrannosaur soft tissue is right? For now, there is compelling evidence for both interpretations. Perhaps more fossils or new analytical techniques will eventually steer the consensus in one direction or the other. Or maybe we will never know for sure what the faces of Dryptosaurus and Tyrannosaurus looked like. For now, Keillor’s models make fascinating companion pieces. They are windows into two possible versions of the deep past, reminding us to accept a little ambiguity now and then.

Got a citation handy for Cope’s comments on the medullary cavities? This is the first I’ve heard of them and I’d be eager to read up.

This was something Tyler Keillor referenced in his talk. I’ll look for it, but you might be able to find it faster!

I remember a sequence in the BBC’s Planet Dinosaur series where paleoartist Doyle Trankina drew two different tyrannosaur sketches, which were just different interpretations of the same evidence. It was really fascinating to see both sides of the debate (and his artwork was awesome too!).

never herd of little clint before and this is my first time hearing about this tiny killer will one day be a true monster of the creataceous

Well no, Clint died as a baby. That’s why we have its fossils! 😉

Here’s a video I helped make about 10 years ago about finding Little Clint, https://youtu.be/l92OZsIUTSA

I’m gonna be honest, I’d rather the dryptosaur sculpture was more fully feathered, or not at all. (Or as near as dammit) The sharply-defined spots and patches in random places are… strange.

Also, I know it’s been done to death already, but Thomas Carr’s scaly-lips findings seem arbitrary and rushed, even to a clueless noob like me.

But those criticisms aside, the sculptures look excellent. I’ve dabbled in epoxy-putty modelling myself – I’m curious to know just what was used on the dryptosaurs.

Hi Warren, thanks for the comment. I thought the feather patches looked weird too, but as Tyler Keilor pointed out in his presentation, the feather-skin margins in modern ground birds are just as defined. It’s just harder to see because the feathers are longer. Check out this ostrich: https://www.arkive.org/ostrich/struthio-camelus/image-G58111.html

Maybe it’s just me, but the Dryptosaurus model at Dunn Museum look a lot like the head model of (alleged) juvenille T-Rex “Jane” at Cleveland MNH.

Yep, the artist said he modeled the head on Jane (which is at the Burpee Museum).