Last time, we covered how Albert Koch turned a tidy profit with his less-than-accurate fossil mounts, leading credible paleontologists to avoid involvement with full-sized reconstructions of extinct animals for much of the 19th century. With the exceptions of Juan Bautista Bru’s ground sloth and Charles Peale’s mastodon, all the fossil mounts that had been created thus far were horrendously inaccurate chimeras assembled by often disreputable showmen. Serious scientists were already struggling to disassociate themselves from these sensationalized displays of imaginary monsters, so naturally they avoided degrading their work further by participating in such frivolous spectacle.

The prevailing negative attitude toward fossil mounts among academics would begin to shift in 1868, when paleontologist Joseph Leidy and artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins collaborated on a mount of Hadrosaurus, the first dinosaur to be scientifically described in America and the first dinosaur to be mounted in the world. While prehistoric animals were well known by the mid-19th century, the Hadrosaurus was so bizarre, so utterly unlike anything alive today, that it truly opened people’s eyes to the unexplored depths of the Earth’s primordial history. I have written about the Hadrosaurus mount before, but its creation was such a landmark event in the history of paleontology and particularly the public understanding of prehistory that it deserves to be contextualized more thoroughly.

Discovering Dinosaurs in Britain

In the early 1800s, American fossil hunters were busy poring over the bones mammoths, mastodons and other mammals. Across the Atlantic, however, it was all about reptiles. Scholars were pulling together the first cohesive history of life on earth, and Georges Cuvier was among the first to recognize distinct periods in which different sorts of creatures were dominant. There had been an Age of Mammals in the relatively recent past during which extinct animals were not so different from modern megafauna, but it was preceded by an Age of Reptiles, populated by giant-sized relatives of modern lizards and crocodilians. The marine ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs unearthed by Mary Anning on the English coast were the first denizens of this era to be thoroughly studied, but they were soon followed by discoveries of terrestrial creatures. In 1824, geologist William Buckland received a partial jaw and a handful of postcranial bones found in the Oxfordshire shale. Recognizing the remains as those of a reptile, Buckland named the creature Megalosaurus, making it the first scientifically described non-avian dinosaur (honoring the unspoken agreement to ignore “Scrotum humanum”).

The partial jaw of Megalosaurus, the first named dinosaur.

Of course, the word “dinosaur” did not yet exist. As covered by virtually every text ever written on paleontological history, it was anatomist Richard Owen who formally defined Dinosauria in 1842 as a distinct biological group. Owen defined dinosaurs based on anatomical characteristics shared by Megalosaurus and two other recently discovered prehistoric reptiles, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus (fatefully, and somewhat arbitrarily, he excluded pterosaurs and doomed paleontologists and educators to forever reminding people that pterodactyls are not dinosaurs). In addition to being an extremely prolific author (he wrote more than 600 papers in his lifetime), Owen was a talented publicist and quite probably knew what he was unleashing. The widely publicized formal definition of dinosaurs, accompanied by displays of unarticulated fossils at the Glasgow Museum, was akin to announcing that dragons were real. By giving dinosaurs their name, Owen created an icon for the prehistoric past that the public could not ignore.

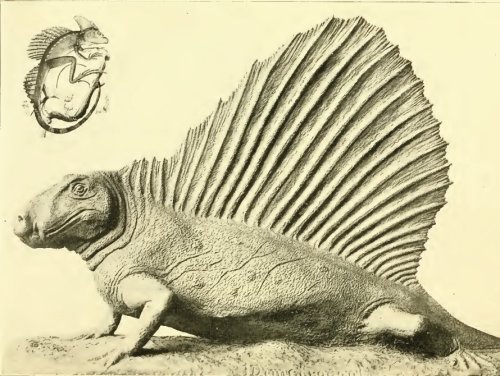

“Dinosaur” soon became the word of the day in Victorian England. Looking to capitalize on this enthusiasm for paleontology, the Crystal Palace Company approached Owen in 1852 to oversee the creation of an unprecedented new exhibit. The company was building a park in the London suburb of Sydenham, meant to be a permanent home for the magnificent Crystal Palace, which had been built the previous year for the Great International Exhibition of the Works and Industry of All Nations. Concerned that the palace would not draw visitors to the park on its own, the Crystal Palace Company commissioned Owen and scientific illustrator Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to create a set of life-sized sculptures of dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures, the first of their kind in the world. The sculptures were a tremendous undertaking: the Iguanodon, for instance, was supported by four 9-foot iron columns, and its body was built up with brick, tile and cement. Hawkins then sculpted its outer skin from more than 30 tons of clay. All told, more than a dozen animals were built, including Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, Hylaeosaurus and an assortment of marine reptiles and mammals.

The Crystal Palace dinosaurs under construction in Hawkin’s studio.

Queen Victoria herself presided over the opening ceremony of Crystal Palace Park in 1854, which was attended by 40,000 people. This was an important milestone because up until that point, only the broadest revelations in geology and paleontology made it out of the academic sphere. But as Hawkins himself put it, the Crystal Palace dinosaurs “might be properly described as one vast and combined experiment of visual education” (Hawkins 1853, 219). The general public could see firsthand the discoveries and conclusions of the most brilliant scientists of their age, in a format that could not only be readily understood and appreciated, but experienced. Full-sized reconstructions of prehistoric animals, including fossil mounts, continue to be built today for precisely this reason.

Recently restored Iguanodon sculptures at Crystal Palace Park. Source

While the Crystal Palace dinosaurs are important historic artifacts and beautiful works of art in their own right, they have not aged well as accurate reconstructions. Owen only had the scrappiest of dinosaur fossils to work with, enough to conclude that they were reptiles and that they were big but not much else. As a result, the Megalosaurus and Iguanodon sculptures look like rotund lizards, as though a monitor lizard or iguana gained the mass and proportions of an elephant. By modern standards, these beasts look pretty ridiculous as representations of dinosaurs, but they were quite reasonable given what was known at the time, at least for a few years.

Dinosaurs of the Jersey Shore

And so at last Hadrosaurus enters the story. Just four years after the unveiling of the Crystal Palace sculptures, the first American dinosaur was found on a farm near Haddonfield, New Jersey (dinosaur footprints and teeth had been found earlier, but their affinity with the European reptiles was not recognized until later). William Foulke, a lawyer and geology enthusiast affiliated with the Philadelphia-based Academy of Natural Sciences, was at his winter home in Haddonfield when he paid a visit to his neighbor, John Hopkins. Hopkins told Foulke that he occasionally found large fossils on his land, which he generally gave away to interested friends and family members. With Hopkins’ permission, Foulke searched the site where the fossils had been found with the assistance of paleontology and anatomy specialist Joseph Leidy. Also a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Leidy is considered the founder of American paleontology and during the mid-1800s, he was the preeminent expert on the subject. At the Haddonfield site, Foulke and Leidy uncovered approximately a third of a dinosaur skeleton, including two nearly complete limbs, 28 vertebrae, a partial pelvis, scattered teeth and two jaw fragments.

All known Hadrosaurus fossils, presently on display at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Now in possession of the most complete dinosaur skeleton yet found, Leidy began studying the fossils of what he would name Hadrosaurus foulkii (Foulke’s bulky lizard) in Philadelphia. The teeth in particular told Leidy that Hadrosaurus was similar to the European Iguanodon. Like Iguanodon, Hadrosaurus was plainly an herbivore, and for reasons left unspecified Leidy surmised that it was amphibious, spending most of its time in freshwater marshes. Leidy noted that Hadrosaurus was a leaner and more gracile animal than Owen’s Crystal Palace reconstructions, but he was particularly interested in “the enormous disproportion between the fore and hind parts of the skeleton” (Leidy 1865). Given the large hindlimb and small forelimb, Leidy reasoned that Hadrosaurus was a habitual biped, and likened its posture to a kangaroo, with an upward-angled trunk and dragging tail. As such, we can credit Leidy for first envisioning the classic Godzilla pose for dinosaurs, which has been known to be inaccurate for decades but remains deeply ingrained in the public psyche.

Although the new information gleaned from Hadrosaurus made it clear that the Crystal Palace sculptures were hopelessly inaccurate, Leidy had been impressed by the Sydenham display and wanted to create a similar public attraction in the United States. Leidy invited Hawkins to prepare a new set of prehistoric animal sculptures for an exhibit in New York’s Central Park. Hawkins set up an on-site studio and began constructing a life-sized Hadrosaurus, in addition to a mastodon, a ground sloth and Laelaps, another New Jersey dinosaur. Unfortunately, Hawkins’ shop was destroyed one night by vandals, apparently working for corrupt politicians. What remained of the sculptures was buried in Central Park and the exhibit was cancelled.

Edit 4/20/2017: Leidy was not actually involved in planning the ill-fated Central Park display. Thanks to Raymond Rye for the tip!

The “Bulky Lizard” Mount

Instead of abandoning the project entirely, Hawkins and Leidy redirected the resources they had already prepared for the Central Park exhibit into a display at the Academy of Natural Sciences museum in Philadelphia. Leidy decided he wanted a mounted skeleton of Hadrosaurus, rather than a fully fleshed model as was originally planned. Such a display had not appeared in a credible museum since Charles Peale created his mastodon mount, but if anybody could get a fossil mount to be taken seriously, it was Leidy.

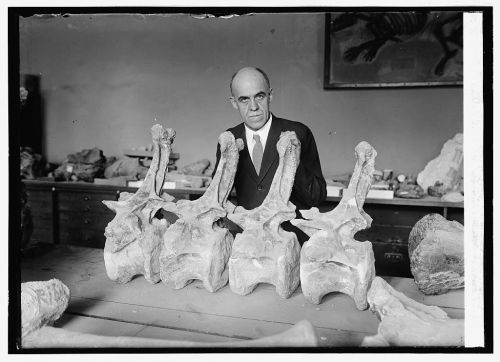

With only a partial Hadrosaurus skeleton to work with, Hawkins had to sculpt many of the bones from scratch, in the process inventing many of the mounting techniques that are still in use nearly a century and a half later. For instance, Hawkins created mirrored duplicates of the left limb bones for use on the animal’s right side, and reconstructed best-guess stand-ins for the skull, scapulae and much of the spinal column using modern animals as reference. Based on photographs like the one below, it appears that portions of the vertebral column were cast as large blocks, rather than individual vertebrae. The mount was supported by a shaped metal rod running through the vertebrae, as well as a single vertical pole extending from the floor to the base of the neck. In fact, very little of the armature appears to have been externally visible, suggesting that making the skeleton as aesthetically clean as possible was a priority.

Hadrosaurus under construction in Hawkins’ studio. Note the flightless bird mounts used for reference. From Carpenter et al. 1994.

The Hadrosaurus mount had a few eccentricities that are worth noting. First, the mount has seven cervical vertebrae, which is characteristic of mammals, not reptiles. Likewise, the scapulae and pelvis are also quite mammal-like. Hawkins was apparently using a kangaroo skeleton as reference in his studio, and it is plausible that this was the source of these mistakes. In addition, Hawkins had virtually no cranial material to work with (despite several repeat visits to the Haddonfield site by Academy members searching for the skull), so he had to make something up. He ended up basing the his sculpted skull on an iguana, one of the few exclusively herbivorous reptiles living today. Although fossils of Hadrosaurus relatives would later show that this was completely off the mark, it was very reasonable given what was known at the time.

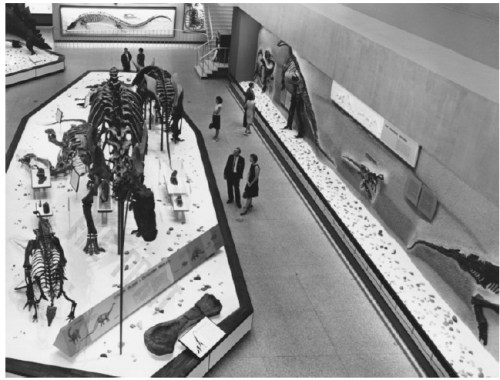

The Hadrosaurus mount was unveiled at the Academy of Natural Sciences musuem in 1868, and the response was overwhelming. The typical annual attendance of 30,000 patrons more than doubled that year to 66,000, and the year after that saw more than 100,000 visitors. Traffic levels were so high that the Academy had to decrease the number of days it was open and enforce limits on daily attendance in order to prevent damage to the rest of the collection. Soon, the Academy was forced to relocate to a new, larger building in downtown Philadelphia, which it still occupies today.

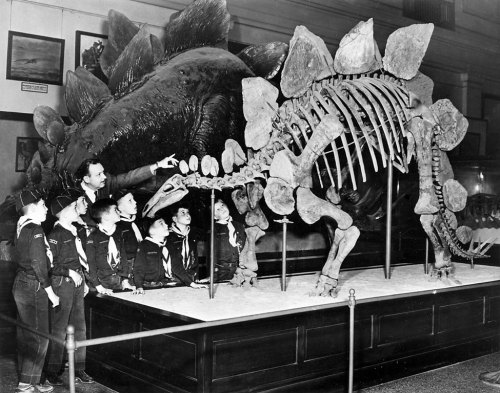

The audience for the Hadrosaurus mount was expanded greatly in the 1870s by three plaster copies of the skeleton, which were sent to Princeton University in New Jersey, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC and the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh (the first dinosaur mount displayed in Europe). The Smithsonian copy had a particularly mobile existence: it was first displayed in the castle on the south side of the National Mall, moved to the dedicated paleontology display in the Arts and Industries Building around 1890, and finally traded to the Field Museum in Chicago later in the decade. In Chicago, the Hadrosaurus was displayed in a spacious gallery alongside mounts of Megaloceros and Uintatherium, and it is in this context that the best surviving photographs of the Hadrosaurus mount were taken. Sadly, by the early 1900s all three casts had been destroyed or discarded by their host institutions, since they had either deteriorated badly or were deemed too inaccurate for continued display. The original Philadelphia mount was also dismantled, although the Hadrosaurus fossils are still at the Academy.

Why was the Hadrosaurus mount such a big deal? For one thing, it was different from previous fossil mounts in that it was the product of the best scientific research of the day. This was not the work of a traveling showman but a display created by the preeminent scientific society of the era, with all the mystique and prestige that came with it. Most importantly, however, the Hadrosaurus mount presented the first ever opportunity to stand in the presence of a dinosaur. By the mid-19th century, western civilization had had ample opportunity to come to terms with the fact that organisms could become extinct, but for the most part the fossils on display were similar to familiar animals like horses, elephants and deer. The Hadrosaurus, however, was virtually incomparable to anything alive today. It was a monster from a primordial world, incontrovertible evidence that the Earth had once been a very different place. By comparison, the Crystal Palace sculptures were essentially oversized lizards, and therefore fairly relateable. The Hadrosaurus was the real turning point, the moment the public got their first glimpse into the depths of prehistory. For 15 years, the Hadrosaurus was the only real dinosaur on display anywhere in the world, so it is no wonder that people flocked to see it.

Of course, the Hadrosaurus was only the beginning of the torrent of dinosaur fossils that would be unearthed in the late 19th century. It would prove to be but a hint at the amazing diversity and scale of the dinosaurs that would be revealed in the American west, as well as the scores of fossil mounts that would soon spring up in museums.

References

Carpenter, K., Madsen, J.H. and Lewis, L. (1994). “Mounting of Fossil Vertebrate Skeletons.” In Vertebrate Paleontological Techniques, Vol. 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Leidy, J. (1865). “Cretaceous Reptiles of the United States.” Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge. 14: 1-102.

Waterhouse Hawkins, B. (1853). “On Visual Education as Applied to Geology.” Journal of the Society of Arts. 2: 444-449.