We know more about dinosaurs today than previous generations of researchers would have ever thought possible. Who would have guessed that in the 21st century, we would have direct evidence for the color of some species, or a detailed understanding of the life history and ontogeny of others? Modern paleontologists can delve deeper into the biology and ecology of extinct animals than ever before, so it comes as a surprise when a very basic question about dinosaur physiology has gone without a definitive answer for well over a century.

For 125 years, paleontogists have struggled to understand how large ceratopsids like Triceratops held their forelimbs. Usually, someone with a good understanding of anatomy can assemble a tetrapod skeleton without much difficulty. Vertebrates are all built along the same basic body plan, and bones fit together in the same general way. However, the forelimb bones of Triceratops and its relatives are quite perplexing. The head of the humerus, which articulates with the scapula, is off-center and extends backward from the shaft. Meanwhile, the lesser tubercle, a tiny nubbin on a human humerus, is enormous and boxy. Taken together, these two traits make it so that if Triceratops held its arm erect and under its body, like most dinosaurs did, the humerus would either puncture the rib cage or be completely dislocated from the shoulder. The simplest way to solve this is to orient the humerus so that the arms project at right angles from the torso, like the sprawling limbs of a lizard. But this just looks wrong. First, ceratopsid hindlimbs are plainly meant to stand straight up. Sprawling forelimbs make Triceratops look mismatched, like the front end a tortoise sewn was to the back end of a rhino. Second, and perhaps more importantly, a sprawling posture would drastically inhibit speed and maneuverability in what is otherwise a very powerfully-built animal. The posture of Triceratops and its kin would ultimately have had a dramatic impact on the animal’s behavior, lifestyle, and ecological role.

Paleontologists haven’t spent the last century just scratching their heads over this problem. Ceratopsid forelimbs have inspired a considerable amount of research over the years, as scientists continue to develop new methods and new tools to explore the biomechanics of prehistoric animals. New technologies have been developed and refined specifically to help determine how Triceratops and its relatives walked and stood. Nevertheless, my intent with this post is not to thoroughly recount the history of ceratopsid forelimb research (if you’re interested, most of the articles referenced below are freely available online). Instead, I’d like to explore the central role museum displays have played in this debate. An artist drawing a two-dimensional image of Triceratops can fudge the orientation of the limbs (and many have), but the team building a mounted skeleton needs to know exactly how to articulate the bones. The ceratopsid posture question first arose in the process of building a mounted Triceratops skeleton for display, and museum mounts continue to be referenced by researchers looking to “ground truth” their ideas. While museum mounts usually exist primarily for education and display, in the case of the ceratopsid forelimb question these exhibits have long been central to the process of studying fossil evidence and creating knowledge.

Early Reconstructions

Marsh’s 1888 restoration of Triceratops.

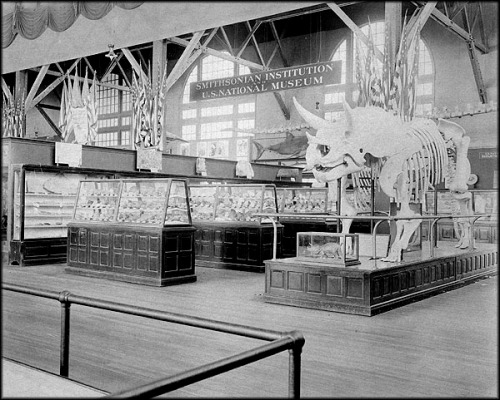

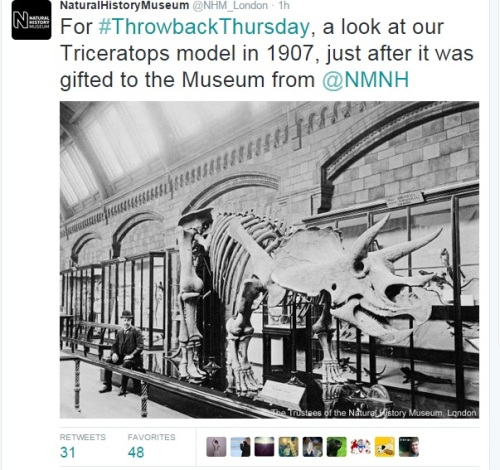

O.C. Marsh published the first illustrated reconstruction of a Triceratops skeleton in 1888. Marsh was legendary in his attention to detail, and the restoration holds up reasonably well today – better, in fact, than his illustrations of Stegosaurus and “Brontosaurus.” Contemporary scientists had no complaints, even though Marsh had given the Triceratops vertical forelimbs. Other dinosaurs had erect limbs, as does the superficially similar modern rhino, so why shouldn’t Triceratops? Marsh’s reconstruction was brought to three-dimensional life in 1901, when the Smithsonian Institution commissioned a life-sized papier mache replica of a Triceratops skeleton for the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. Since the model was hand-sculpted, not casted from original fossils, artist F.A. Lucas had no trouble making Triceratops stand up straight, exactly as portrayed by Marsh. The model appeared again at a Smithsonian exhibit in St. Louis, but was apparently lost or destroyed shortly afterwards. In its place, newly hired United States National Museum preparator Charles Gilmore began work on a mounted Triceratops skeleton composed of original fossils.

Straight-legged Triceratops model at the Pan American Expo in St. Louis. Source

Gilmore’s 1905 Triceratops mount was the first real skeleton of a ceratopsid ever assembled for display (first image). Like virtually all dinosaur mounts of the era, the skeleton was a composite of several specimens and a few sculpted pieces. All the Triceratops fossils at Gilmore’s disposal were collected by John Bell Hatcher in the late 19th century, and inherited by the Smithsonian as part of the Marsh collection. USNM 4842, a partial skeleton consisting mostly of a torso and pelvis, formed the basis for the mount, but at least six other individuals were also incorporated. Gilmore selected the skull because it was more complete and less distorted than the other Triceratops skulls available, but it was also on the small side compared to the body. Likewise, the left humerus was about 40% smaller than the right, and conspicuously three-toed Edmontosaurus hindfeet were used (no Triceratops feet had been found at the time). In the process of building his Triceratops, Gilmore had to make several changes to the idealized Triceratops envisioned by Marsh, most notably the orientation of the forelimbs. Not only was it apparently impossible to articulate the humerus in an upright position, but as Gilmore explained it, “a straightened form of leg would so elevate the anterior portion of the body as to have made it a physical impossibility for the animal to reach the ground with its head.”

The American Museum of Natural History produced their own Triceratops mount in 1923. Like its USNM predecessor, the AMNH Triceratops was a composite of several specimens. AMNH 5033, discovered by Barnum Brown in Montana and consisting of most of the dorsal vertebral column, ribs, and pelvic girdle, made up the largest portion of the mount. The skull was recovered by Charles Sternberg in Wyoming, and many of the appendicular bones were sculpted or cast from Smithsonian specimens. Preparator Charles Lang spent over 263 working days on the project, and much of that time was reportedly spent puzzling over the forelimbs. Lang studied living and preserved specimens of a variety of tetrapods, including rhinos, lizards, crocodiles, and tortoises, trying to find a living analogue for the strangely shaped ceratopsid bones. He ended up articulating the forelimbs so that they were even more widely splayed than Gilmore’s reconstruction, to the point that the back of the Triceratops slopes dramatically forward, and the head is almost dragging along the ground. In an accompanying paper, Henry Osborn asserted that “nothing short of a horizontal humerus and completely everted elbow would permit proper articulation of the facets.” By way of explanation, Osborn offered that this posture might have been helpful in withstanding a frontal impact.

American Museum of Natural History Triceratops mount, circa 1959. Photo courtesy of the AMNH Research Library.

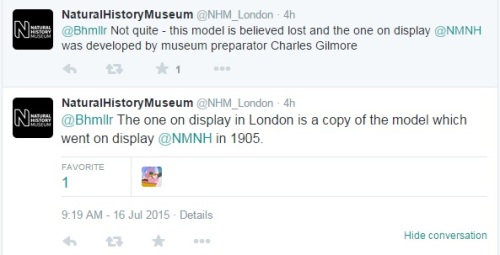

Together, the Washington and New York Triceratops mounts, with their mismatched tortoise-in-the-front, rhino-in-the-back posture, would come to define both popular and scientific conceptions of ceratopsids for the better part of a century. Other museums followed Gilmore and Lang’s lead and built sprawling ceratopsids of their own, including Richard Lull’s 1929 Centrosaurus at the Peabody Museum of Natural History and Kenneth Carpenter’s 1986 Chasmosaurus at the Academy of Natural Sciences. Even as recently as 1995, AMNH curators chose not to change a single bone on the historic Triceratops mount while modernizing their exhibit.

Voices of Dissent

Robert Bakker was one of the first to challenge the ceratopsid forelimb orthodoxy. In 1986, Bakker criticized Gilmore and Lull’s museum mounts and resurrected Marsh’s original interpretation of a straight-legged Triceratops. His reasoning was that the ceratopsid glenoid fossa (the concavity on the scapula that holds the head of the humerus) was more like the narrow cup of a horse or rhino than the wide trough of a lizard. Bakker went as far as to suggest that Triceratops and its kin might have been able to run or even gallop. Gregory Paul and others piled on, arguing that earlier researchers had run into trouble articulating Triceratops forelimbs because they had made the ribcage too broad. If the ribs were articulated so that the animal had flat flanks, the elbow apparently wouldn’t get in the way. Additional evidence for an upright stance came from a set of ceratopsid trackways described by Martin Lockley and Adrian Hunt. The trackways showed forefeet in line with the hindfeet, suggesting that front and back legs were not mismatched, after all.

This cast of the AMNH Triceratops at the Field Museum replicates the sprawling posture of the original. Photo by the author.

However, paleontologists like Peter Dodson were unmoved by these new arguments. Dodson proposed that the trackways had been misinterpreted: since ceratopsids are wider at the hips than at the shoulders, evenly spaced front and back prints should imply that the animal was holding its forelimbs out farther than its hindlimbs. Dodson was concerned that the rhino analogy was being taken too far: Triceratops looked like a rhino, so reasearchers were trying their hardest to make it move and behave like a rhino.

As Kenneth Carpenter explained in a comment last year, dinosaurs can do anything on paper, but physically assembling a skeleton forces you to confront the reality of what the bones can and cannot do. In the last decade, two new Triceratops mounts provided paleontologists the opportunity to re-explore this process, with more complete specimens and modern technology at their disposal. Next time, we’ll take a look at what the new Triceratops displays at the National Museum of Natural History and the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum can tell us about ceratopsid posture and lifestyle.

References

Bakker, R.T. 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of Dinosaurs and Their Extinction. New York, NY: Citadel Press.

Dodson, P. 1996. The Horned Dinosaurs: A Natural History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fujiwara, S. 2009. A Reevaluation of the Manus Structure in Triceratops (Ceratopsia: Ceratopsidae). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29:4:1136-1147.

Fujiwara, S. and Hutchinson, J.R. 2012. Elbow Joint Adductor Movement Arm as an Indicator of Forelimb Posture in Extinct Quadrupedal Tetrapods. Proceedings of the Royal Society 279: 2561-2570.

Gilmore C.W. 1905.The Mounted Skeleton of Triceratops prorsus. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 29:1426:433-435.

Makovicky, P. 2012. Marginocephalia. The Complete Dinosaur, 2nd Edition. Eds. Brett-Surman, M.K., Holtz, T.R. and Farlow, J.O. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Osborn, H.F. 1933. Mounted Skeleton of Triceratops elatus. American Museum Novitates 654:1-14.

Paul, G.S. and Christiansen, P. 2000. Forelimb Posture in Neoceratopsian Dinosaurs: Implications for Gait and Locomotion. Paleobiology 26:3:450-465.