According to the rad personalized 2012 review provided by WordPress, the top search engine terms leading people here over the last year were dinosours, horse evolutionary tree, horse evolution tree, horse phylogenetic tree and Daspletosaurus. It’s not too difficult to pick out the pattern there – horse evolution seems to be a major draw, even though I only mentioned it in a single post back in June. I aim to please, so I suppose a more detailed discussion of horse phylogeny is in order. First off, let me recommend Brian Switek’s thorough and thoughtful take on the subject. If you stick around here, you’re going to get more of a tirade.

Most depictions of horse evolution available online, including the one I posted a few months ago that is luring people to this site, are terrible. The typical linear presentation of horses progressively increasing in size from Eohippus to modern Equus, losing toes along the way, misrepresents not only what we know about horses as a group, but how evolution works in general.

This didn’t happen.

Evolution is, of course, neither linear nor progressive: it is primarily the result of populations adapting to thrive in their particular environments. As environments change over time species may evolve or go extinct, but there is no predetermined goal that lineages are reaching for. Modern Equus is not the most “highly evolved” horse – this is, in fact, a misleading if not meaningless concept, because a species’ success is dependent on its ability to thrive in that specific time and place. A modern horse is well adapted for grazing and running fast on open plains, but relocate one to the Eocene cloud forests where Eohippus thrived and it would do very badly.

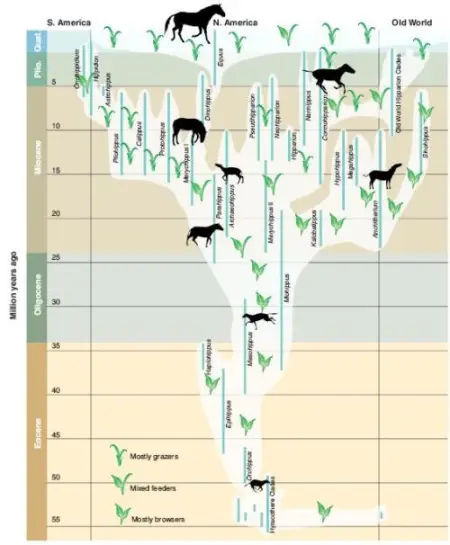

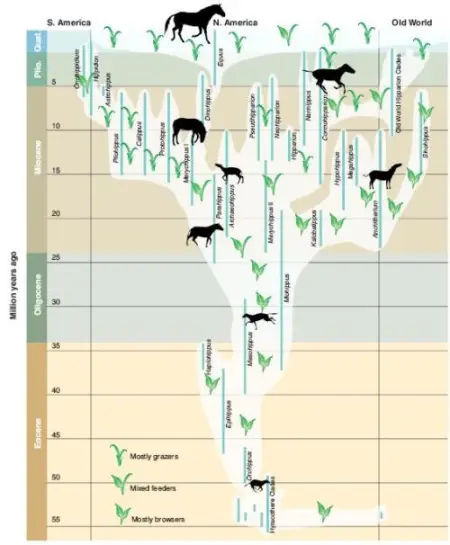

Furthermore, it has been known for over a century that horses as a group did not consistently grow larger over time or otherwise become more Equus-like. Instead, horses diversified into a variety of forms over the group’s 55 million year existence, each group adapting to different environmental niches across the northern hemisphere. Large and small, forest-dwelling browsers and plains-dwelling grazers, these and all manner of other horses overlapped in time and space over the course of the Cenozoic. As J.W. Gidley of the American Museum of Natural History had worked out as early as 1907, horse evolution was not a linear progression but a tangled bush (just like the evolution of most other clades).

A modern horse phylogeny. From MacFadden 2005, via Laelaps.

So where did the orthogenetic depiction of horse evolution come from, and why is it still with us today? The answer highlights the importance of museum exhibits and specimen provenance in the public’s understanding of paleontology, with a dose of jealous personalities for good measure.

In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, in which he articulated the process of evolution by natural selection virtually exactly as we understand it today. Darwin’s book incited a whirlwind of debate in both scientific and public circles because of its implication that the diversity of life could be attributed to natural forces, rather than an unknowable divine power. Within a decade, however, the vast majority of the scientific community was convinced by the soundness of Darwin’s theory, and to this day billions of individual observations of the natural world tell us that evolution is assuredly true.

One of the many lines of evidence covered in On the Origin of Species is the fossil record, with which we can trace the evolution and extinction of organisms over time, including the ancestors of modern life. However, Chapter 9 of Darwin’s book, “On the Imperfection of the Geological Record” (full text pdf) reads like like a lengthy apology for the incomplete nature of fossil preservation. Today, the use of organized, cladistic methodologies allow paleontologists to piece together detailed phylogenies from fossils, but in Darwin’s day, the evidence was patchier, and he opted to de-emphasise the fossil record’s usefulness to avoid such criticism. As Darwin put it, “we have no right to expect to find in our geological formations an infinite number of of those fine transitional forms.” Unfortunately for paleontology specialists, this led other biologists to believe that fossils could not make any independent contribution to the understanding of evolution. Largely shut out of the biggest biological discovery of all time, paleontologists became stewards of a “second-class discipline” (Sepkoski 2012, 9).

Paleontologists in the late 19th century.

Since biologists interested in evolution considered paleontology mostly irrelevant, late 19th-century paleontologists were left with three options. They could support evolution as best they could and accept that other biologists might not take notice, they could ignore theoretical discussion entirely and focus on purely descriptive studies of morphology, or they could be spiteful and seek alternatives to Darwinian evolution. The second course of action was the most popular well into the 20th century. E.D. Cope seems to be an example of the third approach, favoring an odd sort of neo-Lamarckism in his book The Origin of the Fittest. Such conceptions of directional change, such as Cope’s Law, are counter to evolution as proposed by Darwin and as understood today. However, a handful of paleontologists stuck with it and endeavored to provide meaningful fossil evidence for evolutionary theory.

Throughout the 1860’s, paleontologist O.C. Marsh amassed an impressive array of fossil horses from Wyoming and elsewhere in the American west. Horse fossils had been found in Europe much earlier, but Marsh’s horse collection was much more complete, and was probably the best fossil record compiled for any vertebrate group at the time. In 1870, the influential British naturalist Thomas “Darwin’s Bulldog” Huxley visited Marsh in New Haven and was suitably impressed: Marsh’s fossils ranged from the Eocene up until the Pleistocene, providing a clear picture of how the horse family had evolved over time. While Darwin had been hesitant to make too big a deal about the fossil record as evidence for evolution, the horse fossils were blatant examples of animals changing over time.

During the same visit, Huxley gave a lecture in New York in which he cited the horse fossils as a fantastic new line of evidence in support of evolution. Unfortunately, Huxley’s lecture (while admittedly aimed at a general audience) tread into some severely teleologic territory. As quoted in The Gilded Dinosaur (Jaffe 2000, 162), Huxley told his audience that “the horse is in many ways a most remarkable animal in as much as it presents us with an example of one the most perfect pieces of machinery in the animal kingdom.” He went on to explain how horse ancestors, from the little four-toed Hyracotherium in the Eocene to increasingly large horses like Merychippus and Pliohippus, gradually perfected the design of the modern horse. According to Huxley, over the course of the Cenozoic horses got bigger, faster, leggier, and generally better at being horses as we know them today. Problematically, this essentialist narrative rather misses the point of evolution as described by Darwin.

Marsh, like Huxley, was an early advocate of evolution, but his narrative of horse evolution was more on the mark. Marsh concluded that the smaller early horses with brachydont teeth were well suited for life in the rainforests that covered the western United States 50 million years ago. Horses like we know them today emerged as a direct result of the Earth getting cooler and drier over the course of the Cenozoic, and by the end of the Pleistocene the lineages of forest horses were completely extinct. Equus is with us today not because it is the best horse for any circumstance, but because it was most successful during the ice ages that shaped the modern flora and fauna (it also helped that humans figured out that horses are useful and ensured their survival through domestication).

Unfortunately, Marsh was never enthusiastic about public education, and so the progressive view of horse evolution was the one that made it into the public sphere. The history of horses remained a popular example of evidence for evolution, trotted out over the years by prominent biologists like George Simpson and Stephen Gould. Indeed, it was the first good evolutionary story known from fossils, although by no means the last or the best. In the earliest 1900s, Henry Osborn had a major role in solidifying the orthogenetic horse evolution story in the public eye when he curated the exhibit on the subject at the American Museum of Natural History. It is on the basic premise of this exhibit that the textbook, museum, and web descriptions of linear horse evolution that persist to this day are based.

The fossil horses of AMNH. Photo by the author.

After the modern biological synthesis, paleontologists realigned with the rest of biology, and the odd pseudo-evolutionary ideas that persisted in paleontological circles began to fall by the wayside. However, orthogenetic ideas remain common in natural history exhibits on horse evolution to this day (in about 62% of them, according to MacFadden et al. 2012). The reason these exhibits have stuck around isn’t entirely clear. MacFadden and colleagues suggest suggest a lack of inertia or funding for the renovation of exhibits is a factor, but they also point out that even some newer exhibits fall back on linear horse evolution.

The biggest problem is that orthogenetic evolution makes more intuitive sense to non-specialists. We often use the word “evolution” to imply improvement, so it would follow that horses should get bigger and better over time. This is an important misconception to overcome, because, as if we need a reminder, only 15% of Americans believe humans evolved from other animals via strictly natural processes, and an even smaller number can correctly articulate how evolution works. Evolution is the fundamental principle underlying everything we see in the natural world, and it is imperative that a correct understanding of how it works is the basis of any biology education. With the proper background, the real story of horse evolution is a great example of how changing climates effect organisms and ecosystems over time. This is helpful for interpreting the ever-important subject of climate change, but it won’t click until the linear horse evolution story is trampled out for good.

References

Jaffe, M. 2000. The Gilded Dinosaur: The Fossil War Between E.D. Cope and O.C. Marsh and the Rise of American Science. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

MacFadden, B.J., Oviedo, L.H., Seymour, G.M. and Ellis, S. 2012. “Fossil Horses, Orthogenesis and Communicating Evolution in Museums.” Evolution, Education and Outreach 5:29-37.

Sepkoski, D. 2012. Rereading the Fossil Record: The Growth of Paleobiology as an Evolutionary Discipline. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.