Last week, I checked two major fossil exhibits off my must-see list – the Morian Hall of Paleontology at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and Life Then and Now at the Perot Museum in Dallas. Although both exhibits opened the same year and cover the same basic subject matter, they are radically different in terms of aesthetics, design, and interpretation. Life Then and Now is unabashedly excellent and pretty much embodies everything I called a Good Thing in my series on paleontology exhibit design. I’ll be sure to discuss it in detail later on. Nevertheless, I’m itching to write about the HMNS exhibit first because it’s—in a word—weird. The Morian Hall essentially rejects the last quarter century of conventional wisdom in developing fossil displays, and for that matter, science exhibits of any kind.

The Morian Hall occupies a brand-new 36,000 square foot addition to HMNS, apparently the largest in the museum’s history. The first thing I noticed walking into the exhibit was that the space doesn’t look like any other science exhibit I’ve seen, past or present. Instead, it strongly resembles a contemporary art gallery, and this fossils-as-art aesthetic permeates every aspect of the exhibit design. Specimens are displayed against stark white backgrounds, with smaller fossils in austere wall cases and larger mounted skeletons on angular, minimalist platforms. Most objects are displayed individually, with lots of negative space between them. Interpretive labels, where present, are small and out of the way (and the text is all in Helvetica, because of course it is). There are no interactive components of any kind—no movies, no computer terminals, not even question-and-answer flip-up panels. The exhibit is defined by its own absence, the structural elements and labels fading into the background with the intent that nothing distract from the specimens themselves.

For the benefit of those outside the museum field, I should clarify that for myself and many others trained in science and history museums, art museums are basically opposite world. In an art museum, objects are collected and displayed for their own sake. Each artwork is considered independently beautiful and thought-provoking, and curators often strive to reduce interpretation to the bare minimum. Some museums have gone so far as to forgo labels entirely, so that objects can be enjoyed and contemplated simply as they are. Not coincidentally, art museums have a reputation as being “highbrow” establishments that attract and cater to a relatively narrow group of people. People who do not fit the traditional definition of art museum visitor sometimes find these institutions irrelevant or even unwelcoming (more on that in a moment). This summation is hardly universal, but I would argue that the participatory, audience-centered art museum experiences created by Nina Simon and others are an exception that proves the rule.

Natural history museums are different. Collections of biological specimens are valuable because of what they represent collectively. These collections are physical representations of our knowledge of biodiversity, and we could never hope to understand, much less protect, the natural world without them. Each individual specimen is not necessarily interesting or even rare, but it matters because it is part of a larger story. It represents something greater, be it a species, a habitat, or an evolutionary trend. Likewise, modern natural history exhibits aren’t about the objects on display, but rather the big ideas those objects illustrate. Since the mid-2oth century, designers have sought to create exhibits that are accessible and meaningful learning experiences for the widest possible audience, and natural history museums are generally considered family-friendly destinations.

There is much to like in the Morian Hall of Paleontology. For one thing, the range of animals on display is incredible. I cherished the opportunity to stand in the presence of a standing Quetzalcoatlus, a Sivatherium, a gorgonopsid, and many other taxa rarely seen in museums. Other specimens are straight-up miracles of preservation and preparation, including a number of Eocene crabs from Italy. I also enjoyed that many of the mounts were in especially dynamic poses, and often interacting with one another. With fossil mount tableaus placed up high as well as at eye level, there was always incentive to look around and take in every detail.

Nevertheless, the art gallery aesthetic raised a number of red flags for me. To start, the minimalist design means that interpretation takes a serious hit. Although the exhibit is arranged chronologically, there are many routes through the space and the correct path is not especially clear. Meanwhile, there are no large headings that can be seen on the move—visitors need to go out of their way to read the small and often verbose text. All this means that the Morian Hall is an essentially context-free experience. Visitors are all but encouraged to view the exhibit as a parade of cool monsters, rather than considering the geological, climatic, and evolutionary processes that produced that diversity. There is an incredible, interrelated web of life through time on display in the Morian Hall, but I fear that most visitors are not being given the tools to recognize it. By decontextualizing the specimens, the exhibit unfortunately removes their meaning, and ultimately their reality*.

*Incidentally, most of the mounted skeletons are casts. This is quite alright, but I was very disappointed that they were not identified as such on accompanying labels.

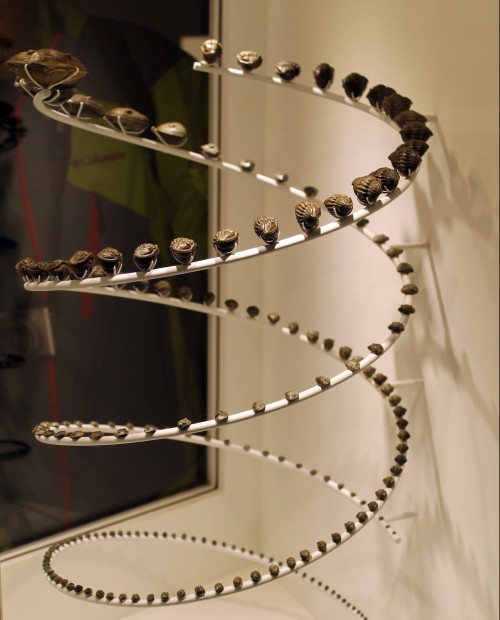

This double-helix trilobite growth series is gorgeous—but what does it communicate, exactly? Photo by the author.

What’s more, the idealized, formal purity of the exhibit design echoes a darker era in the history of museums. It’s no secret that many of the landmark museums we know today were born out of 19th century imperialism. Colonial domination was achieved not only with military power, but through academia. When colonial powers took over another nation, they brought their archaeologists, naturalists, and ethnographers along to take control of the world’s understanding of that place, its environment, and its people. Museums were used to house and display natural and cultural relics of conquered nations, and to disseminate western scientists’ interpretation of these objects. Even today, it is all too common to see ethnographic objects displayed in austere exhibit spaces much like the Morian Hall of Paleontology. These displays erase the objects’ original cultural meaning. Dinosaurs don’t care about being silenced, of course, but it’s odd that HMNS would choose to bring back such loaded visual rhetoric.

Pretty ammonites with donor names prominently displayed send the wrong message. Photo by the author.

My final concern with the art gallery format is the implication that fossils have monetary value. Fossils are priceless pieces of natural heritage, and they cannot be valued because they’re irreplaceable. While there is a thriving commercial market for rare fossils, a plurality of paleontologists do not engage with private dealers. Buying and selling significant fossils for private use is explicitly forbidden under the ethics statement of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, and it is institutional policy at many museums that staff never discuss the monetary value of fossil specimens.

The art world has its own rules and standards. The price tags of famous pieces, including what a museum paid to acquire them, are widely known. Private collectors are celebrated, even revered. In fact, it is common to see exhibits built around a particular individual’s collection. These exhibits are not about an artist or period but the fact that somebody purchased these objects, and has given (or merely loaned) them to the museum. Two rooms in the Morian Hall are actually just that: otherwise unrelated specimens displayed together because they were donated by a specific collector. By displaying specimens with the same visual language as art objects, the Morian Hall undermines the message that fossils should not be for sale. Not only is the private fossil trade legitimized, it communicates that the primary value of fossils is their aesthetic appeal. Like the lack of contextual signage, this serves to obscure the specimens’ scientific meaning. Fossils are precious remains of real organisms, clues about ecosystems from long ago and the making of the world as we know it today. But that information is only available if they are publicly accessible, not sitting on someone’s mantelpiece.

A truly remarkable fossil mount tableau, in which a mastodon flings a human hunter while a mammoth is driven off a “cliff” in the background. Photo by the author.

Now hold on (regular readers might be saying), haven’t I argued repeatedly that fossil mounts should be considered works of art? Absolutely, and that is part of why I was taken aback by this exhibit. The difference is that while the Morian Hall displays fossils the way art is traditionally exhibited, it does not interpret them like art. When I call fossil mounts works of art, I mean that they have authorship and context. They have encoded and decoded meaning, as well as relationships with their viewers, creators, host institutions, and ultimately, the animals they represent. Calling something art is opening it up to discussion and deconstruction. The HMNS exhibits do the opposite.

For the last few decades, natural history museums have been opening windows onto the process of creating knowledge. Modern exhibits seek to show how scientists draw conclusions from evidence, and invite visitors to do the same. In the Morian Hall, those windows are closed. Specimens are meant to be seen as they are, reducing the experience to only the object and the viewer. But there is no “as they are” for fossils. Thousands of hours of fossil preparation and mount construction aside, every display in that exhibit is the result of literally centuries of research into geology, anatomy, and animal behavior. These are representations of real animals, but they also represent the cumulative interpretive work of a great many people. The display simply isn’t complete without their stories.

This is horrible. Gorgeous, but horrible. It sends the message that there is nothing to know about the exhibits!

Excellent post, and great observations. There are a few other museums that take an almost art-gallery approach in terms of the colour and design – I’m sure everyone is familiar with the AMNH exhibit halls, and the Royal Ontario Museum’s updated fossil halls have a similar aesthetic. Both of these exhibits use the white walls to draw attention to the fossils, but I think they also both incorporate a lot of good interpretation to the fossils as well in terms of signage (and it’s hard not to think of a better phylogenetically-oriented exhibit than the AMNH’s with its literal cladogram on the floor). The Tyrrell also has a room in which specimens are literally framed in fancy art frames, and while I think it’s a beautiful room with amazing specimens I recall the interpretive materials being a bit less prominent in there compared to the rest of the museum.

I think ‘decluttering’ exhibits so that you make the maximum impact with limited attention spans and time is important, but removing almost all interpretive materials isn’t the way to do it. Context-less fossils aren’t as interesting and I don’t think a museum fulfills its educational goals when that occurs. Honestly, when I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently I was really annoyed by the scarcity of interpretive materials throughout. Even with modern artworks, I would like to hear the artist’s interpretation and goals for their work in order to compare with my own. I’d also like to learn about artistic trends, the history of art, etc. etc. Maybe art museums could learn a thing or two from science museums.

Hi Victoria, thanks for weighing in! I had the same thought at MMA – I consider myself a casual art enthusiast but I think many art exhibits are stuck in an outmoded and uninteresting exhibit model.

One thing that came up on twitter is that the alternative to sparse interpretation isn’t essays on the wall, and it isn’t excessive use of videos and interactives either. It’s challenging – but quite possible! – to provide a contextual story in an elegant way. For example, I love the “fly-by” headings the Field Museum uses:

Most visitors will see the “welcome to a world of water” and “first animals like nothing ever before” headings even if they just walk by. And those two phrases already establish a solid context for the Cambrian fossils they’ll be seeing in the next room.

Great post, its always great to read about natural history displays in the US especially from someone in the know. Firstly I was intrigued as I work for museums and art galleries and thought ‘oo fossils in a gallery context might be interesting’ but after seeing the photos I can see why this is worrying and I agree that it ‘supports’ private fossil collecting. I think that museums that display their fossils in a art gallery way must have other forms of interpretation such as guides but if this is not the case I can imagine the public are being let down in regards to information and education (isn’t that what they’re for besides collections of course?). By taking a fossil out of context it looses all meaning to science and this will not come across in this minimal interpretation approach. If anything this museum is damaging the potential general public outlook on palaeontology, not informing or educating them. I can imagine you wouldn’t spend your money visting again or stay the whole day if the interpretation is minimal and in turn wouldn’t this hinder the museum in one way or another? Makes me wonder what made them do this!

Two very contrasting museums that also do this are Stuttgart and Eichstatt, both very good museums in different ways.

1) “Fossils are priceless pieces of natural heritage, and they cannot be valued because they’re irreplaceable. While there is a thriving commercial market for rare fossils…”

Um, what? The very next sentence contradicts the claim in the first. If there is a commercial market then fossils must obviously have monetary value. Also Museum of the Rockies doesn’t think they are irreplaceable – “If they’re stolen or destroyed, would we buy new ones? No, we would not… We would dig for new ones, probably.” (http://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/montana_state_university/state-demands-museum-of-rockies-put-dollar-value-on-fossils/article_84eaea84-cd6a-5879-aabd-f598de146dd3.html)

And that is a key difference between art and fossils. There is only one Mona Lisa. There are multiple T rexes and there will always be more to be discovered. They might be rare but they are not one of a kind. Yet, somehow the art museums are able to deal with pieces that are worth much more than the average fossil price-wise than natural history museums are. Why is this? I bet you it’s because they are more likely to cooperate with private collectors rather than attempt to file lawsuits against them.

2) You seem to disdain displaying once privately owned fossils collections in museums. Why? If you were designing an exhibit and a private fossil collector said I want to donate my very rare fossils to display in your museum but on the condition that they are to be in a special exhibit accredited to me, would you turn that person down? Is that making science better off?

3) I am not sure if you are insinuating that sleek, modern, and visually appealing museums exhibits are imperialistic. The connection seems rather loose. It is one thing to suggest more scientific information be available to the public in the exhibit, but imperialistic, really??

And while it is important to have updated scientific information, there is also something to be said about fossils not being dug up with name-tags. The visually appealing bones are the information, and much of scientific knowledge about them is our interpretation of that information. So in that sense it could be argued that the less text in a museum, the purer the information and the less likely it will be outdated. Houston could have spent a some of the money on informational media rather than fossil display but then in 50 years time people will be blogging about how it’s outdated exhibit is an affront to science (I’m not suggesting this is the best approach, but just something to think about)

Hi Polly, thanks for sharing your thoughts.

1. My understanding is that the paleontology staff at MOR are generally opposed to the valuation of their collection, but it is being forced on them by the state. That’s the gist of the article you linked to, anyway.

Let’s talk about your argument that there are always more dinosaurs to be found. Firstly, there is certainly a real ceiling to the number of specimens that were ever fossilized (or fossilized in accessible places). Then there are financial and staff limits at the institutions that collect fossils. Since you brought up T. rex, only fifty or so individuals have been found in the past 110 years, and of those, only about a dozen are more than 50% complete. And that’s an especially well-represented dinosaur. Most dinosaur species are known from a single incomplete specimen.

So yes, the number of specimens available (and will ever be available) is infinitesimally small. And at the specimen level, there really is only one. A given fossil that was referenced in a given paper is the only one that will ever exist. As Lisa Buckley put it, the cost of replacing any specimen is “one time machine.” If it’s gone, it’s gone. And that’s not even getting into examples from localities that have been lost or destroyed…

2. I have no problem with once-privately owned fossils being donated to museums, and I’m not sure where you got that idea. As you say, it’s important for science that specimens be in publicly-accessible repositories.

3. “Visually appealing” is of course in the eye of the beholder, but there are many sleek, modern-looking natural history exhibits that also manage to tell informative stories. See, for example, the LACM dinosaur exhibit and the NMNH mammals hall. The art gallery aesthetic described in this post involves a very specific set of aesthetic principles, including a de-emphasis on interpretation in favor of displaying objects in a “neutral” setting. This is what I’m opposed to.

There is a great deal of literature on the colonial history of museums, especially the erasure and silencing of source cultures when displaying ethnographic objects outside their original context. A few examples are below. As I stated above, the fossils don’t care about being silenced, but art gallery imagery is very loaded and comes from a problematic tradition.

Haraway, D. 1985. Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936. Social Text 11: 20-64.

Henderson, A. and Kaeppler, A.L. (eds). 1997. Exhibiting Dilemmas: Issues of Representation at the Smithsonian. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Kohlstedt, S.G. (2005). Thoughts in Things: Modernity, History, and North American Museums. Isis 96: 4: 586-601.

Saunders, B. 2001. The photological apparatus and the desiring machine: Unexpected congruences between the Koninklijk Museum, Tevuren and the Umista Centre, Alert Bay. Academic Anthropology and the Museum. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Vogel, S. 1991. Always True to the Object, In Our Fashion. Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Displays. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

1) There is a finite number of any given type of extinct animal that existed in the past and therefor, a finite number of its fossils. But let’s be real here, how many paleontologists are there? Should we be worried about exhausting the supply of trilobites the way we are worried about exhausting oil reserves. Of course not. If you showed me a fossil of anything, and I told you that there are probably no more to be found and we should not bother looking for that species anymore, would you agree and go focus on something else? No. How many T rexes must be found before you wouldn’t bother looking for more? Realistically, we are never going to stop looking, and I doubt we are ever going to cease finding them. How many fossils are still deeply buried?

I think anyone who spends time finding fossils of any type would disagree with the characterization that their reserves are “infinitesimally small”. Someone who doesn’t look for fossils might believe that however.

So what if the concept of the specimen-level is irreplaceable? If a biologist studies a living creature and publishes on it, is the science invalid after the animal dies? Of course not. It’s the same thing with fossils, they are just less convenient to find than many living animals are. Also, should scientists avoid publishing work using destructive analysis? By the ‘specimen-level irreplaceable logic’, that should not be allowed….. Seems silly to me.

Going back to the idea of a price tag. I don’t see how anyone – you, me, Buckley, etc. – can fool themselves into thinking that fossils don’t have a monetary value when they are sold everyday. What should one think when they see a fossil with a price tag in a gem shop? The label doesn’t apply? If you simply took it for a museum, could you argue that it wasn’t theft because fossils are “priceless”? Also scientists love price tags on fossils when it allows them to bag commercial collectors for felony level theft of fossils after the amount of fossils stolen reaches a minimum dollar value. You can’t have it both ways.

2) The reason I thought you were not a fan of displaying private collections was this –

“In fact, it is common to see exhibits built around a particular individual’s collection. These exhibits are not about an artist or period but the fact that somebody purchased these objects, and has given (or merely loaned them) to the museum. Two rooms in the Morian Hall are actually just that: otherwise unrelated specimens displayed together because they were donated by a specific collector. By displaying specimens with the same visual language as art objects, the Morian Hall undermines the message that fossils should not be for sale.”

Sounds like condemnation but maybe I misread it. Are you saying that it is okay as along as they aren’t displayed as “Mr. Smith’s fossil trilobite collection”, for example? I’m saying that doing so might be the only way to make those fossils available to museums. You can’t criticize that as anti-science because it is biting the hand that feeds. Something art museums are smart enough not to do.

3) Museums might have imperialistic pasts. But saying that a particular aesthetic to an exhibit is problematic because of concerns of past imperialism is a big stretch. I doubt the houston museum has much of a imperialistic past anyway. To me, it just sounds like making an issue out of something that isn’t an issue. The architecture of the natural history museum in NY could be argued to conjure up the same history. Should the building be completely remodeled? No, that would be ridiculous. So is taking issue with a particular exhibit’s aesthetic based on some fanciful concerns over imperialism.

Also, art and archeological artifacts have cultural underpinnings as man-made objects. Fossils are products of nature, not culture. But that is besides the point.

Great post. I have enjoyed reading your blog for a while and was wondering when you would get around to covering the HMNS hall.

As a Rice University student, I’ve spent some nice personal time with the specimens in this hall (free admission!). I agree with your general sentiments about the exhibit design being a mixed bag, particularly about the lack of guidance/structure as to geologic time, evolution, and other grander contexts. The copious open spaces and pathways don’t help – shortly after entering the hall one can skip right to the Allosaurus and Stegosaurus in sight (which are admittedly much ‘sexier’ than the stromatolites and Ediacaran organisms at the exhibit’s beginning!). Similarly, once in the dinosaur portion of the hall it’s easy to go right to the three T. rex specimens displayed.

I feel the exhibit signage does a good job of informing visitors, but only those so inclined (and with sufficient time – during my first visit I spent a couple hours and didn’t even get past the Mesozoic specimens) to actually read and seek to learn more about the displayed specimens and their temporal/evolutionary context (due to the small text and signs being spread out). However I think the main information panels (with the Csotonyi illustrations) do a great job of educating on the main specimens displayed – visitors (even the young kids!) often stop and read those. I feel a more streamlined and enclosed architecture along with some larger, more condensed signage would help with ensuring the average visitor walks away with a better understanding of the evolutionary narrative, as it’s very easy to jump around between specimens not particularly related to each other and gloss over the smaller signs. The two side rooms with the petrified wood and various ammonites/eurypterids/etc. also aren’t particularly helpful as to this regard as they don’t fit into any particular temporal/evolutionary context.

That being said, the ‘art museum’ aesthetic is not without its benefits. For those of us so inclined, it allows for a truly up close appreciation of some really spectacular specimens. Forget the dinosaurs, the ammonites and trilobites are absolutely breathtaking! My heart swoons at specimens like the ammolite Placenticeras and exquisitely prepared spiny trilobites. Even fellow non-paleontologically inclined students of mine have a big impression left on them by these specimens (particularly the trilobites), which I think is constructive for helping people see that there’s more to prehistory than dinosaurs and mammoths. And I’ve overheard visitors contemplating the great effort required to find and preserve fossils after seeing some of the more elaborate trilobite specimens, which is probably something they hadn’t considered before. Even with the larger specimens visitors can get pretty up close and personal (unlike some other museums where they’re roped off and visitors can only look from afar), which allows for some pretty close anatomical observation and comparison. Of course this primarily applies to those already interested and having a decent background knowledge in paleontology vs the layman.

Overall the exhibit is definitely valuable for those actively seeking to be educated and less so to the average person visiting on the weekend, but then I can’t think of many that aren’t that way to some extent. And for those of us with basic paleontological knowledge, it is an almost unparalleled opportunity to examine some exquisite specimens.

p.s. The gift shop has a wonderful selection of reasonably accurate dinosaur toys.

Sadly, the day I visited was when the gift shop was closed for inventory!

I like your point that the exhibit is especially useful for people who already know a bit about the history of life… it definitely is! And like you say, I do appreciate that there are no glass barriers around the mounts so you can really get in close.

My intention with this post was certainly not to trash the exhibit. I enjoyed my time there, but many of the design decisions are not the ones I would have made, and more importantly, they’re very different from most other large-scale natural history exhibits made in the last 10-20 years.

I definitely agree with you on the design decisions being different from most other exhibits – the HMNS hall certainly makes a different impression than most other museums I’ve been to. That being said I look forward to your post on the Perot museum, as I’ve never been.

Polly:

As I said before, most any individual specimen has the potential to provide new data. Fossils of the same species are not interchangeable. Therefore, any significant fossil in private hands is a loss to science.

“I think anyone who spends time finding fossils of any type would disagree with the characterization that their reserves are “infinitesimally small”. Someone who doesn’t look for fossils might believe that however.”

Collecting and preparing fossils is a significant part of my job, and I’ve taken part in field work throughout the US and abroad. So yeah, I feel like I have a decent handle on the rarity and intellectual value of fossils.

“I don’t see how anyone – you, me, Buckley, etc. – can fool themselves into thinking that fossils don’t have a monetary value when they are sold everyday. What should one think when they see a fossil with a price tag in a gem shop? The label doesn’t apply?”

Yes, obviously there are many people who are willing to put a price tag on fossils. I am not one of those people. My understanding is that most vertebrate paleontologists would agree here. Again, it’s part of the SVP ethics statement.

“Also scientists love price tags on fossils when it allows them to bag commercial collectors for felony level theft of fossils after the amount of fossils stolen reaches a minimum dollar value. You can’t have it both ways.”

I have no idea what you are alluding to here.

“Are you saying that it is okay as along as they aren’t displayed as “Mr. Smith’s fossil trilobite collection”, for example?”

Yes. It’s fairly typical for museums with significant paleontology programs to avoid buying specimens from private collectors. The inflated price tags would fund years of original research and field work, after all. There are occasionally exceptions (hey Sue!), but these decisions aren’t always supported by research staff. Most museums do not accept donated specimens with strings attached, or anything where the provenance is not known (often a problem with private market fossils).

“The architecture of the natural history museum in NY could be argued to conjure up the same history. Should the building be completely remodeled? No, that would be ridiculous. So is taking issue with a particular exhibit’s aesthetic based on some fanciful concerns over imperialism.”

I strongly disagree here.

Just to be clear, I am sorry if my comment has upset you. That was not my intention.

However, I would like to continue discussing this as I am not yet convinced by your arguments and I think the topics discussed are important.

Let’s look at three of your statements.

1) most any individual specimen has the potential to provide new data.

2) Fossils of the same species are not interchangeable.

3) Therefore, any significant fossil in private hands is a loss to science.

I agree with the 1st and 3rd points. However, not all fossils are significant. If someone showed up and offered a moving truck jam-full of specimens of a common ammonite species would you be able or willing to curate them in a museum? Probably not worth the time, space, money, or effort, right? So should they then be thrown back into the sea or kept in private hands if no museum is willing to take them? Obviously if an individual specimen is destroyed or lost then there is no replacing that specimen, but it does not mean that the data it provides cannot be replaced. If a scientist does a statistical study of 200 of those common ammonites, does the next scientist necessarily have to study those exact 200 specimens to investigate the first’s claims or can they use a different 200? If scientific scrutiny *absolutely* depended on examining the same specimen in all cases then many fields of science are in trouble. Like I said, how can you justify destructively studying bone in paleontology? Are all of the modern advances in destructive studies not real science? It is frustrating when significant, rare fossils are in private hands but one cannot let it dictate their entire approach to dealing with private collectors or designing exhibits. See this blog for a call for cooperation and engaging head on with private collectors – http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/museums/2013/12/04/natural-history-under-the-hammer/.

I am surprised that you think fossils are rare despite your extensive experience in the field. My hunch is that what we once thought was scarcity actually just reflects the small number of paleontologists (amateur or professional) throughout the history of the science relative to today. See this article about 5 T rexes recently dug in one summer – http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/965609.stm. I also remember hearing about fossils being so common in dinosaur provincial park in Canada that they often don’t even bother collecting all the bone they find.

Just because someone thinks fossils (or any objects) are priceless and refuses to appraise them on whatever grounds, “ethics” or otherwise, does not mean that they don’t have monetary value. If the bank wanted to repossess your house would you argue your case by saying the house is priceless because to you it is your ‘home’ not just a piece of property? Paleontologists need to accept reality the way every other science has, in addition to the art world. I cannot think of any other STEM field with such a distrust and refusal to work with the private/commercial/industrial sector. I don’t even hear of archeologists being as heated over private collections as paleontologists and those objects actually have cultural ties. Some of the greatest scientific advancements are due to commercial greed, for lack of a better work (ex. genetic engineering or the prized fossils of the most famous museums in the world that were dug by commercial collectors).

Also, as for what I was alluding to previously. All I meant to suggest was that the society of vertebrate paleontology has previously inserted itself into legal situations (see the comments about letter from SVP to the attorney regarding Sue in the comments section of this article http://observationdeck.kinja.com/dinosaur-13-tells-part-of-the-story-of-sue-1676260414).

So if a private owner wanted to outright donate a highly significant fossil to a museum but insisted that their name be plastered on the exhibit, you would refuse? I still can’t wrap my head around how that position is in the best interest of science.

The idea that money spent by a museum in purchasing a specimen is less advisable than funding their own field work is simply not a universally true business strategy. Sure, the amount of money could fund a lot of field work but there is no guarantee of finding fossils of the same quality – this is exactly the point you make when you say that specimens are irreplaceable! Engaging with the sale of fossils might make more or less sense depending on the museum, it’s location, and how well developed the collections are. A large, old museum with many fossils in its collection located in a fossil rich area might be a bigger benefit to science by meticulously collecting odds and ends on their own that only scientists might find of interest. While a young, small museum located far from fossil rich areas would be better by purchasing an impressive, significant specimen to display to attract visitors and encourage visiting researchers so as to make a name for itself and become established. If you look at the history of museums this is often how the biggest, most renowned ones got their start – by obtaining fossils from private collectors or paying commercial paleontologists. The Denver museum of nature and science started off as one mans private collection! (http://www.dmns.org/about-us/museum-history) That clearly turned out for the best, but if Edwin Carter was around today, he would be demonized by scientists for having a private collection and trying to start his own private museum (as we have seen regarding the museum in Thermopolis WY). Simply dismissing purchasing fossils as an option severely limits the business flexibility of museums and makes it harder for new ones to become established, meaning stagnation in the number of academic jobs, a loss of science, and missed opportunities for outreach. If one museum does not want to purchase a fossil, it should not demonize the practice if another museum does want to. it’s about doing what is best for science.

As for a lack of contextual data accompanying privately owned specimens, regulating the market (like how owning big cats is regulated) to ensure a paper trail of this information surely is the answer rather than condemning or trying to eliminate the market entirely (then it just becomes an even shadier black market like in China).

I still do not see how an exhibit’s aesthetic can lead to any sort of tangible effect regarding imperialism. Could you explain the mechanism or the effects that might be associated with producing an exhibit with such an aesthetic?

Hi Polly, I think it’s pretty clear that we’re not going to agree (which is fine, these are issues that have been debated for decades!), so I’ll just address your new points.

“However, not all fossils are significant. If someone showed up and offered a moving truck jam-full of specimens of a common ammonite species would you be able or willing to curate them in a museum? Probably not worth the time, space, money, or effort, right?”

You’re right, it’s important to differentiate between different kinds of fossils and their relative rarity. I believe the NPS and BHM have some parameters in place regarding invertebrate versus vertebrate fossils, for example. I’ve been implicitly talking about substantially complete vertebrate specimens like Tyrannosaurus, since it’s what you brought up first.

“If a scientist does a statistical study of 200 of those common ammonites, does the next scientist necessarily have to study those exact 200 specimens to investigate the first’s claims or can they use a different 200?”

Depends on the study question, but yes, this is often important. A big part of science is replicability of results from the same data.

“The idea that money spent by a museum in purchasing a specimen is less advisable than funding their own field work is simply not a universally true business strategy.”

Here’s the thing: a museum isn’t a business. It’s a public service. Museums don’t make money, and they shouldn’t operate under business principles if it’s a detriment to their mission.

“If you look at the history of museums this is often how the biggest, most renowned ones got their start – by obtaining fossils from private collectors or paying commercial paleontologists. The Denver museum of nature and science started off as one mans private collection!”

I don’t think this is a fair comparison, in part because a century ago far fewer institutions had in-house labs and staff capable of building up collections, and in part because private collectors weren’t charging seven figures (or the inflation-adjusted equivalent) back then.

Thanks so much for covering HMNS, Ben.

I used to live in Houston, and I would often visit HMNS.

I haven’t been on these Discovery Tours personally (http://www.hmns.org/visit/discovery-tours/), but I hear they are very informative. Of course, it would definitely be better if the type of information provided on these tours are also available in the form of labels within the exhibit.

As you pointed out, many of these mounts are casts. As a matter of fact, you can identify a number of these casts that were purchased from the Black Hills Institute (http://www.bhigr.com/store/home.php?send_isJS=Y&send_browser=YYN|Safari|537.36|MacIntel|Y|1680|1050)

I’m also curious as to your opinion on the Black Hills Institute, since they are a company that provides fossils for sale to not only museums but also to private collectors.

Hi Robert, thanks for the reply. I didn’t take a tour at HMNS but I did overhear part of a field trip group, and the presenter seemed both knowledgeable and good at interacting with kids (equally important!). My concern with relying on guided tours for information is the accessibility issue. They cost extra at HMNS, they don’t run round-the-clock, they’re hard to pitch at multiple age groups simultaneously, and they aren’t appealing to everyone – many museumgoers report that they avoid tours like a plague and prefer to take exhibits at their own pace.

As you can tell from the comment thread, I’m pretty adamant that selling vertebrate fossils for profit is fundamentally problematic. That said, I’m a fan of BHI because they’ve made high-quality casts available to small and mid-sized museums around the world. Not long ago, the experience of standing in the presence of a dinosaur like T. rex was only possible in a handful of cities, but BHI has played a big part in making dinosaur displays widely available.

I left a reply but it doesn’t seem to be coming up.

We visited the HMNS this summer, and while they obviously have a fantastic collection and this exhibit showcases it beautifully, I was similarly struck by the total lack of interpretative information. I was beginning to suspect that it was a deliberate choice in the paleontology exhibits to avoid talking about evolution, especially after my husband mentioned that he’d noticed a similar phenomenon at the Charlotte biology museum — but then we went through the mineralogical gallery and found the exact same thing there! So I suppose I have to acknowledge it as an aesthetically-driven choice.

My other major objection to the design of the Hall of Paleontology was acoustic. The concrete floor, high ceilings, and half-height walls added up to a distressing level of white noise. Not something I’d ever noticed in a paleontology exhibit before, but, again, very art-gallery-like.