Old meets new: The classic Carnegie T. rex (CM 9380) is now paired with a cast of Peck’s Rex (MOR 980). Photo by the author.

Start with Displaying the Tyrant King – Part 1.

In 1915, the American Museum of Natural History unveiled the first mounted skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex ever constructed. The Carnegie Museum of Natural History followed suit with their Tyrannosaurus mount in 1941, and for most of the 20th century New York and Pittsburgh were the only places in the world where the tyrant king could be seen in person. Nevertheless, these displays propelled Tyrannosaurus to universal stardom, and the instantly recognizable dinosaur appeared in countless books, films, and other media for years to come.

The omnipresence of T. rex was secured in part by two additional museum displays, ironically at institutions that did not have any actual Tyrannosaurus fossils on hand. The Field Museum of Natural History commissioned Charles Knight to paint a series of prehistoric landscapes in 1928, the most recognizable of which depicts a face-off between Triceratops and a surprisingly spry Tyrannosaurus. In 1947, Rudolph Zallinger painted a considerably more bloated and lethargic T. rex as part of his Age of Reptiles mural at the Peabody Museum of Natural History. Both paintings would be endlessly replicated for decades, and would go on to define the prehistoric predator in the public imagination.

Rex Renaissance

Despite enduring public enthusiasm, scientific interest in dinosaurs declined sharply in the mid-20th century, and new discoveries were few and far between. This changed rather suddenly with the onset of the “dinosaur renaissance” in the 1970s and 80s, which brought renewed energy to the discipline in the wake of evidence that dinosaurs had been energetic and socially sophisticated animals. The next generation of paleontologists endeavored to look at fossils in new ways to understand dinosaur behavior, biomechanics, ontogeny, and ecology. Tyrannosaurus was central to the new wave of research, and has been the subject of hundreds of scientific papers since 1980. More interest brought more fossil hunters into the American west, leading to an unprecedented expansion in known Tyrannosaurus fossils. Once considered vanishingly rare, Tyrannosaurus is now known from over 50 individual specimens across a wide range of ages and sizes. Extensive research on growth rate, cellular structure, sexual dimorphism, speed, and energetics, to name but a few topics, has turned T. rex into a veritable model organism among dinosaurs.

RTMP 81.6.1, aka Black Beauty, mounted in relief at the Royal Tyrell Museum. Source

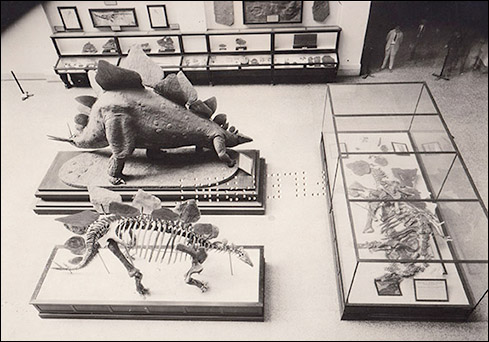

The most celebrated Tyrannosaurus find from the early years of the dinosaur renaissance came from Alberta, making it the northernmost and westernmost T. rex to date. The 30% complete “Black Beauty” specimen, so named for the black luster of the fossilized bones, was found in 1980 by a high school student and was excavated by paleontologist Phil Curie. The original Black Beauty fossils were taken on a tour of Asia before finding a permanent home at the newly established Royal Tyrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta. In lieu of a standing mount, Black Beauty was embedded in a faux sandstone facade, mirroring the environment in which the fossils were found and the animal’s presumed death pose. This relief mount set Black Beauty apart from its AMNH and CMNH predecessors, and even today it remains one of the most visually striking Tyrannosaurus displays. Since the original specimen consisted of less than half of a skeleton, much of this display is made up of sculpted bones, including the pelvis, scapula, and most of the ribs. The mounted skull is a cast, but the real skull is displayed behind glass nearby. A complete cast of Black Beauty in a traditional free-standing mount is also on display at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm.

The World’s Most Replicated Dinosaur

Driven by the increased public demand for dinosaurs, many museums without Tyrannosaurus fossils of their own have purchased complete casts from other institutions. In 1986, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia opened “Discovering Dinosaurs”, the world’s first major exhibit showcasing active, endothermic dinosaurs. The centerpiece of the exhibit was a cast of the original AMNH Tyrannosaurus, posed for the first time in the horizontal posture that we now know was the animal’s habitual stance. The following year, another AMNH cast appeared in the lobby of Denver Museum of Nature and Science in a strikingly bizarre pose, with one leg kicking high in the air. The mount’s designer Robert Bakker intended to push boundaries and demonstrate what a dynamic and energetic Tyrannosaurus might be capable of, although the mount has subsequently been described as dancing, kicking a soccer ball, or peeing on a fire hydrant. Meanwhile, The Royal Tyrell Museum prepared a mount of RTMP.81.12.1 (a specimen consisting of a relatively small number of postcranial bones) that was filled in with AMNH casts, including the highly recognizable skull.

Tyrannosaurus cast at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Source

Since the late 1990s, however, casts of another specimen have overtaken AMNH 5027 for the title of most ubiquitous T. rex. BHI 3033, more commonly known as Stan, was excavated in South Dakota in 1992 by the Black Hills Institute, a for-profit outfit specializing in excavating, preparing, and mounting fossils. Stan is significant for being over two-thirds complete and for including the best-preserved Tyrannosaurus skull yet found. BHI has sold dozens of casts of the Stan skeleton to museums and other venues around the world. At a relatively affordable $100,000 plus shipping, even small local museums and the occasional wealthy individual can now own a Tyrannosaurus mount. With over 50 casts sold as of 2017, Stan is, by a wide margin, the most duplicated and most exhibited dinosaur in the world.

All these new Tyrannosaurus mounts are forcing museums to get creative, whether they are displaying casts or original fossils. Predator-prey pairings are a popular display choice: for example, the Houston Museum of Natural Science T. rex is positioned alongside an armored Denversaurus, and the Los Angeles Natural History Museum matches the tyrant dinosaur with its eternal enemy, Triceratops. Meanwhile, the growing number of juvenile Tyrannosaurus specimens has allowed for family group displays. A second T. rex exhibit at LACM features an adult, subadult and baby, while the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis pairs a Stan cast with the original skeleton of Bucky, a “teenage” T. rex. The most unique Tyrannosaurus mount so far is certainly the copulating pair at the Jurassic Museum of Asturias.

Each of these displays gives a substantially different impression of Tyrannosaurus. Depending on the mount, visitors might see T. rex as a powerful brute, a fast and agile hunter, or a nurturing parent (or a gentle lover). Each mount is accurate insofar that a real Tyrannosaurus probably adopted a similar stance at some point, but the museum’s choice of pose nevertheless influences visitors’ understanding of and attitude toward the dinosaur.

Restoring the Classics

With dozens of new Tyrannosaurus mounts springing up across the country and around the world, the original AMNH and CMNH displays began to look increasingly obsolete. Unfortunately, modernizing historic fossil mounts is an extremely complex and expensive process. The early 20th century technicians that built these displays generally intended for them to be permanent: bolts were drilled directly into the bones and gaps were sealed with plaster that can only be removed by manually chipping it away. What’s more, the cumulative effects of rusting armatures, fluctuating humidity, and vibration from passing crowds have considerably damaged historic mounts over the course of their decades on display.

Despite these challenges, AMNH and CMNH have both been able to restore and update their classic Tyrannosaurus displays. While fossil mounts used to be built in-house, often by the same people who found and described those fossils, modern mounting projects are typically outsourced to specialist companies. Phil Fraley Productions, an exhibit fabrication company based in the Pittsburgh suburbs, was responsible for both T. rex restorations. At AMNH, Jeanne Kelly spent two years disarticulating and conserving each bone before Phil Fraley’s crew took over to build the new armature. The new mount not only corrected the dinosaur’s posture, but improved visitors’ view of the fossils by removing obstructive vertical supports. Instead, most of the skeleton’s weight is now supported by steel cables hanging from the ceiling. Each bone is secured to an individual metal bracket, allowing researchers to easily remove elements for study as necessary. A new cast of the skull was also prepared, this time with open fenestrae for a more natural appearance. Rather than attempting to match the dramatic and showy T. rex mounts at other museums, the AMNH team chose a comparatively subdued stalking pose. A closed mouth and subtly raised left foot convey a quiet dignity befitting this historically significant display.

Historically, the 1941 CMNH Tyrannosaurus had never quite lived up to its New York predecessor. Although it incorporated the Tyrannosaurus type specimen, it was mostly composed of casts from the New York skeleton, and it sported an unfortunately crude replica skull. It is therefore ironic that CMNH now exhibits the more spectacular T. rex display, one which finally realizes Osborn’s ambitious plan to construct an epic confrontation between two of the giant predators. As they had with the AMNH mount, Phil Fraley’s team dismantled the original display and painstakingly removed many layers of paint, shellac, and plaster from the bones. Michael Holland contributed a new restored skull, actually a composite of several Tyrannosaurus skulls. The restored holotype T. rex now faces off with a cast of “Peck’s Rex”, a specimen recovered from Montana in 1997. Despite the difficulty of modernizing the historic specimen, the team reportedly developed a healthy respect for turn of the century mount-makers like Adam Hermann and Arthur Coggeshall, who developed the techniques for making enduring displays of fragile fossils that are still being refined today.

Continue to Displaying the Tyrant King Part 3.

References

Colbert, E.H., Gillette, D.D. and Molnar, R.N. “North American Dinosaur Hunters.” The Complete Dinosaur, Second Edition. Brett-Surman, M.K., Holtz, T.R. and Farlow, J.O., eds.Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Dingus, L. 1996. Next of Kin: Great Fossils at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Johnson, K. and Stucky, R.K. 2013. “Paleontology: Discovering the Ancient History of the American West.” Denver Museum of Nature and Science Annals, No. 4.

Larson, N. 2008. “One Hundred Years of Tyrannosaurus rex: The Skeletons.” Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King. Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth, eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Naish, D. 2009. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Norell, M., Gaffney, E.S. and Dingus, L. 1995. Discovering Dinosaurs: Evolution, Extinction, and the Lessons of Prehistory. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Psihoyos, L. 1994. Hunting Dinosaurs. New York, NY: Random House, Inc.