The original Tyrannosaurus rex mount at the American Museum of Natural History. Photo from Dingus 1996.

Woodrow Wilson is in the white house. The first World War is raging in Europe, but the United States is not yet involved. The women’s suffrage movement is picking up speed. And you just heard that the skeleton of an actual dragon is on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. It is difficult to imagine a time before every man, woman, and child in the developed world knew the name Tyrannosaurus rex, but that world existed not even a century ago. In 1915, AMNH unveiled the very first mounted skeleton of the tyrant lizard king, immediately and irrevocably cementing the image of the towering reptilian carnivore in the popular psyche.

Today, Tyrannosaurus is a celebrity among dinosaurs, appearing in every form of media imaginable. More importantly, however, it is an icon for paleontology and an ambassador to science. The cult of T. rex began in the halls of museums, and museums remain the prehistoric carnivore’s symbolic home. The mounted skeletons in museums provide the legendary T. rex its credibility: these are the authentic remains of the giant predator that once stalked North America. And yet, most of the dozens of Tyrannosaurus skeletons on display around the world are casts, and none of them represent complete skeletons (rather, they are filled in with spare parts from other specimens and the occasional sculpted bone). These are sculptures as well as scientific specimens, works of installation art composed by artists, engineers, and scientists. Herein lies the paradox presented by all fossil mounts: they are natural specimens and constructed objects, embodying a challenging duality between the realms of empiricism and imagination.

A Tyrannosaurus mount is at once educational and spectacular. Both roles were embraced at AMNH in 1915, and these dual identities have defined T. rex displays ever since. 14 years ago, FMNH PR 2081, also known as Sue, became a star attraction for the Field Museum of Natural History and the city of Chicago at large. Later this month, another T. rex will unwittingly take on a similar role: on April 15th, MOR 555, an 80% complete Tyrannosaurus specimen discovered in Montana, will be dubbed “The Nation’s T. rex“ and entered into the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collection with considerable fanfare.

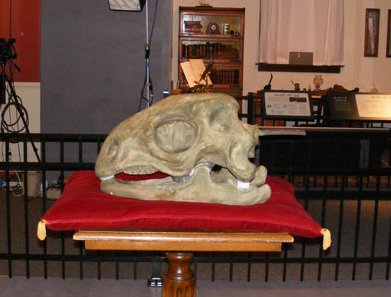

Skull cast of MOR 555, soon to be “The Nation’s T. rex“, at the National Museum of Natural History. Photo by the author.

This three part series is a look back at how the tyrant king has defined, and been defined by, the museum experience. Part 1 will cover the circumstances surrounding the creation of the iconic original Tyrannosaurus mount in New York, as well as its successor in Pittsburgh. Part 2 will explore the changing role of Tyrannosaurus in museums caused by a surge of new fossil finds and a revolution in our understanding of dinosaurs. Finally, Part 3 will conclude with a discussion of the positives and negatives of a modern world saturated in all things T. rex.

The Original Tyrant

Between 1890 and 1910, the United States’ large urban natural history museums entered into a frenzied competition to find and display the largest and most spectacular dinosaur skeletons. Although the efforts of paleontologists O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope in the late 19th century fleshed out the scientific understanding of Mesozoic reptiles, it was these turn-of-the-century museum displays that brought dinosaurs into the public sphere. Bankrolled by New York’s wealthy aristocrats and led by the ambitious mega-tool Henry Osborn, AMNH won the fossil race by most any measure. The New York museum completed the world’s first mounted skeleton of a sauropod dinosaur in 1905, and also left its Chicago and Pittsburgh competitors in the dust with the highest visitation rate and the most fossil mounts on display.

Osborn’s goal was to establish AMNH as the global epicenter for paleontology research and education, and in 1905 he revealed his ace in the hole: two partial skeletons of giant meat-eating dinosaurs uncovered by fossil hunter Barnum Brown. In a deceptively brief paper in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, Osborn described the fossils from Wyoming and Montana, coining the names Dynamosaurus imperiosus and Tyrannosaurus rex (a follow-up paper in 1906 reclassified “Dynamosaurus” as a second Tyrannosaurus specimen). Fully aware of what a unique prize he had in his possession, Osborn wasted no time leveraging the fossils for academic glory (and additional funding from benefactors). He placed the unarticulated Tyrannosaurus fossils on display at AMNH shortly after his initial publication, and commissioned legendary artist Charles Knight to prepare a painting of the animal’s life appearance.

In 1908, Brown collected a much more complete Tyrannosaurus specimen (AMNH 5027), with over 50% of the skeleton intact, including the first complete skull and a significant portion of the torso. With this specimen in hand, AMNH technician Adam Hermann and his team began work on a mounted Tyrannosaurus skeleton to join the Museum’s growing menagerie of mounted dinosaurs and prehistoric mammals. Inspired by the Museum’s collection of taxidermy mounts in dynamic habitat dioramas, and seeking to accentuate the spectacle of his reptilian monster, Osborn initially wanted to mount two Tyrannosaurus skeletons facing off over a dead hadrosaur. He even published a brief description complete with illustrations of the projected scene (shown below). However, the structural limitations inherent to securing heavy fossils to a steel armature, as well as the inadequate amount of Tyrannosaurus fossils available, made such a sensational display impossible to achieve.

Instead, Hermann prepared a single Tyrannosaurus mount, combining the 1908 specimen with plaster casts of leg bones from the 1905 holotype. The original skull was impractically heavy, so a cast was used in its place. Finally, missing portions of the skeleton, including the arms, feet, and most of the tail, were sculpted by hand using bones from Allosaurus as reference. During the early 20th century, constructing fossil mounts was a relatively new art form, and while Hermann was one of the most talented and prolific mount-makers in the business, his techniques were somewhat unkind to the fossil material. Bolts were drilled directly into the fragile bones to secure them to the armature, and in some cases steel rods were tunneled right through the bones. Any fractures were sealed with plaster, and reconstructed portions were painted to be nearly indistinguishable from the original fossils. Like most of the early AMNH fossil mounts, preserving the integrity of the Tyrannosaurus bones was often secondary to aesthetic concerns like concealing the unsightly armature.

AMNH Tyrannosaurus, ca. 1940. Photo courtesy of the AMNH Research Library.

The completed Tyrannosaurus mount, a magnificent sculptural combination of bone, plaster, and steel, was unveiled in 1915 to stunned audiences. The December 3rd New York Times article was thick with hyperbole, declaring the dinosaur “the prize fighter of antiquity”, “the king of all kings in the domain of animal life,” “the absolute warlord of the earth” and “the most formidable fighting animal of which there is any record whatsoever” (and people say that today’s science journalism is sensationalist!). With its tooth-laden jaws agape and a long, dragging lizard tail extending its length to over 40 feet, the Tyrannosaurus was akin to a mythical dragon, an impossible monster from a primordial world. This dragon, however, was real, albeit safely dead for 66 million years.

Today, we know that the original AMNH Tyrannosaurus mount was inaccurate in many ways. The upright, tail-dragging pose, which had been the most popular attitude for bipedal dinosaurs since Joseph Leidy’s 1868 presentation of Hadrosaurus, is now known to be incorrect. More complete Tyrannosaurus skeletons have revealed that the tail reconstructed by Osborn and Hermann was much too long. The Allosaurus-inspired sculpted feet were too robust, the legs (casted from the 1905 holotype), were too large compared to the rest of the body, and the hands had too many fingers (the mount was given proper two-fingered hands when it was moved in 1927). It would be misleading to presume that the prehistoric carnivore’s skeleton sprang from the ground exactly as it was presented, but it is equally problematic to reject it as a fake. There are many reasons to criticize Osborn’s leadership at AMNH, but he did not exhibit outright forgeries. The 1915 Tyrannosaurus mount was a solid representation of the best scientific data available at the time, presented in an evocative and compelling manner.

The AMNH Tyrannosaurus mount was no less than an icon: for paleontology, for its host museum, and for the city of New York. The mount has been a New York attraction for longer than the Empire State Building, and for almost 30 years, AMNH was the only place in the world where visitors could see a T. rex in person. In 1918, Tyrannosaurus would make its first Hollywood appearance in the short film The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. This star turn was followed by roles in 1925’s The Lost World and 1933’s King Kong, firmly establishing the tyrant king’s celebrity status. It is noteworthy that special effects artist Willis O’Brian and model maker Marcel Delgado copied the proportions and posture of the AMNH display exactly when creating the dinosaurs for each of these films. The filmmakers apparently took no artistic liberties, recreating Tyrannosaurus precisely how the nation’s top scientists had reconstructed it in the museum.

A T. rex for Pittsburgh

In 1941, AMNH ended it’s Tyrannosaurus monopoly and sold the incomplete type specimen (the partial skeleton described in Osborn’s 1905 publication) to Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History. While it is sometimes reported that this transfer took place to keep the valuable fossils out of harm’s way during World War II (e.g. Larson 2008), the deal was apparently underway well before the United States became involved in the war. Having paid an astounding $100,000 ($1.7 million in today’s dollars) for the fossils, CMNH staff wasted no time in assembling a mount of their own. The Tyrannosaurus holotype only included only about 15% of the skeleton, so most of Pittsburgh mount had to be made from casts and sculpted elements. Somewhat pointlessly, the skull fragments included with the specimen were buried inside a plaster skull replica, making them inaccessible to researchers for several decades. Completed in less than a year, the CMNH Tyrannosaurus was given an upright, tail-dragging posture very much like its AMNH predecessor.

CM 9380 at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Source

The mid-20th century is sometimes called the “quiet phase” in vertebrate paleontology. After enjoying public fame and generous federal support during the late 1800s, paleontology as a discipline was largely marginalized when experiment-driven “hard” sciences like physics and molecular biology rose to prominence. By the 1950s and 60s, the comparably small number of researchers studying ancient life were chiefly concerned with theoretical models for quantifying trends in evolution. Although the aging dinosaur displays at American museums remained popular with the public, these animals were perceived as evolutionary dead-ends, of little interest to the majority of scientists. Between 1908 (when Brown found the iconic AMNH Tyrannosaurus skeleton) and 1980, only four largely incomplete Tyrannosaurus specimens were found, and no new mounts of this species were built.

Continue to Displaying the Tyrant King Part 2.

References

Dingus, L. (1996). Next of Kin: Great Fossils at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Glut, D. 2008. “Tyrannosaurus rex: A century of celebrity.” Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King. Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth, eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Hermann, A. 1909. “Modern Laboratory Methods in Vertebrate Paleontology.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 21:283-331.

Larson, N. 2008. “One Hundred Years of Tyrannosaurus rex: The Skeletons.” Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King. Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth, eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

“Mining for Mammoths in the Badlands: How Tyrannosaurus Rex Was Dug Out of His 8,000,000 Year old Tomb,” The New York Times, December 3, 1905, page SM1.

Naish, D. 2009. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Osborn, H.F. 1906. “Tyrannosaurus, Upper Cretaceous Carnivorous Dinosaur.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 22:281-296.

Osborn, H.F. 1913. “Tyrannosaurus, Restoration and Model of the Skeleton.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 32:9-92.

Rainger, Ronald 1991. “An Agenda for Antiquity: Henry Fairfield Osborn and Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, 1890-1935. Tuscaloosa, Alabama. University of Alabama Press.

Wesihampel, D.B. and White, Nadine M. 2003.The Dinosaur Papers: 1676-1906. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books.