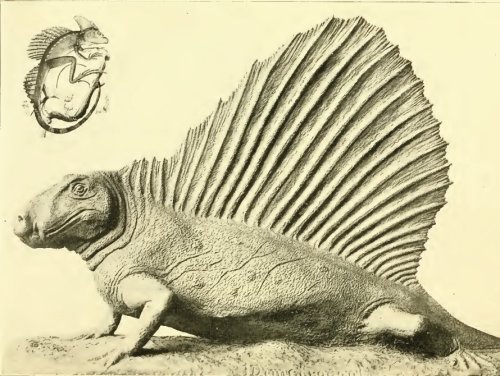

Back in July, I wrote about how the forelimb posture of ceratopsian dinosaurs like Triceratops has puzzled paleontologists for more than a century. Most quadrupedal dinosaurs held their front legs straight under their bodies, and it would make sense if Triceratops and its kin did the same. However, when researchers attempted to physically articulate skeletons for museum displays, they found that that the humerus would only fit properly with the scapula if it projected horizontally from the torso – like the sprawling limbs of a lizard. Over the years, new specimens, new research methods, and new technologies have all been used to help resolve this conundrum, but a consensus has not yet been reached. Of particular interest to me is the unusually central role mounted skeletons in museums have played in this biomechanical mystery. The previous post covered the historic Triceratops mounts; this entry will take a look at some more recent Triceratops displays in American museums.

The Hatcher Project

In 1998, a visitor looking at the Triceratops mount at the National Museum of Natural History happened to sneeze. To her alarm, the sneeze was enough to knock a small fragment of bone off the pelvis and onto the floor. The visitor thoughtfully informed security, and after a thorough conservation assessment by Kathy Hawks, it was determined that the 93-year-old mount needed to come off exhibit, and soon. The delicate fossils had served valiantly through 23 presidential administrations, but now it was time for the skeleton to be disassembled and preserved for posterity.

Retiring the classic Triceratops gave Ralph Chapman, head of the Museum’s Applied Morphometrics Laboratory, an opportunity to take on a project he had been germinating for some time. Chapman wanted to demonstrate the potential of 3-D scanning technology for paleontology research by creating a high-resolution digital duplicate of a dinosaur skeleton. Today, the process of making and studying digital copies of fossils is both widespread and remarkably straightforward, but in the late 1990s it was practically science fiction. Nevertheless, the historic Triceratops was an ideal digitization candidate for several reasons. First, the digital assets would reduce handling of the delicate and aging original fossils. Second, exact copies of the scanned bones could be made from milled foam and plastics to create a replacement exhibit mount. Finally, a digital Triceratops would be a great opportunity to revisit the ceratopsid posture problem in a new way.

A rendering of the digital Hatcher. Source

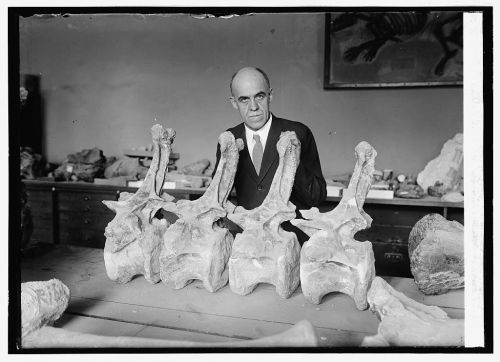

The ensuing Hatcher Project (the Triceratops was named in honor of John Bell Hatcher, who found the original fossils in the late 19th century) was a collaboration between Museum staff and several industry experts, including Lisa Federici of Scansite 3-D Services and Arthur Andersen of Virtual Surfaces, Inc. The first step was to place stickers on 100 key points on the Triceratops. These points were recorded with a surface scanner, so that the historic mount could be digitally recreated in its original pose. After that, fossil preparators Steve Jabo and Pete Kroehler carefully dismantled the skeleton. Each bone from the skeleton’s right side* was then scanned individually, producing 20 gigabytes of data (you’re supposed to gasp…again, this was the late 90s).

*Bones from the right side were mirrored to reproduce the left half of the skeleton.

Since the original mount had been a somewhat disproportionate composite, the team made a few changes when building the new digital Hatcher. Some elements, including the undersized skull, were enlarged to match the rest of the skeleton. In addition, parts that had either been sculpted or were not actually Triceratops bones – such as the dorsal vertebrae and the hindfeet – were replaced with casts acquired from other museums. The result was the world’s first complete digital dinosaur, and shortly afterward, the first full-sized replica skeleton generated from digital assets.

Hatcher’s seldom seen right side was briefly exposed recently, before the mount was moved to a temporary second floor location. Source

In April 2000, the Hatcher team convened at NMNH to determine how the new replica mount would be posed. Chapman, Jabo, and Kroehler were joined by Kent Stevens of the University of Oregon, Brenda Chinnery of Johns Hopkins University, and Rolf Johnson of the Milwaukee Public Museum (among others) to spend a day working with a 1/6th scale model produced by stereolithography specialist Jason Dickman. The miniature Hatcher allowed the researchers to physically test the skeleton’s range of motion without the difficulty of manipulating heavy fossils.

The day was full of surprises. The team was impressed by the wide range of motion afforded by the ball and socket joint connecting the Triceratops skull to the atlas. They also found that the elbow joints could lock, which may have been helpful for shock absorption when the animal smashed things with its face. Nevertheless, when it came time to articulate the humerus and scapula, the team essentially validated Charles Gilmore’s original conclusion that sprawling forelimbs worked best (although the new Hatcher mount stands a little straighter than the historic version, and a lot straighter than the New York Triceratops). While other paleontologists had used indirect evidence (like evenly spaced trackways and wide nasal cavities for sucking down lots of oxygen) to support the idea that Triceratops was a straight-legged, fast-moving rhino analogue, articulating the actual bones showed once again that ceratopsid forelimbs had to sprawl.

Houston and Los Angeles Mounts

LACM Triceratops mount. Photo by Heinrich Mallison, many more here.

Hatcher is the Triceratops I am best acquainted with, and I can’t help but think of it as the definitive example of this animal. However, two new Triceratops mounts demonstrate a radically different take on ceratopsid posture. In 2011, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County completed a thoroughly renovated dinosaur hall, which features a brand-new Triceratops mount at its entrance. Like Hatcher, this skeleton is a composite of several specimens, in this case excavated in Montana by LACM teams between 2002 and 2004. Phil Fraley Productions, the exhibit fabrication company behind Sue and the Carnegie Museum dinosaurs, was responsible for mounting the fossils. The primary specimen (LACM 141459, which provided the skull and right forelimb) is notable because it included a completely intact and articulated front leg. Although the analysis of this important find has yet to be published, exhibit curator Luis Chiappe tellingly chose an erect, rather than sprawling, forelimb posture.

Meanwhile, the Houston Museum of Nature and Science opened its colossal, 30,000 square foot Hall of Paleontology in 2012. Among the dozens of mounted skeletons on display is Lane, reportedly the most complete Triceratops ever found. The museum purchased the skeleton from the Black Hills Institute, and the company also constructed the display mount. Robert Bakker, who curates the Hall of Paleontology, specifically requested that Lane be given a straight-legged, trotting pose. With two legs off the ground, this display emanates strength and speed.

“Lane” at Houston Museum of Nature and Science. Source

So how did the Los Angeles and Houston exhibit teams manage to construct plausible-looking, straight-legged Triceratops mounts? Since full descriptions of either specimen have not been published, it’s hard to say for sure. From the look of it, however, the new mounts both have narrower, flatter rib cages (as suggested by Paul and Christiansen), which allows more room for the elbow. Likewise, the shoulder girdles are lower than Hatcher’s, and they seem to have been rotated closer to the front of the chest. Also note that the forelimbs of the Los Angeles and Houston mounts are not completely erect – they are strongly flexed at the elbow, as is typical of many quadrupedal mammals.

These new mounts don’t mean the Triceratops posture problem is resolved, though. The angle of the ribs and the position of the scapula are apparently both touchy subjects, so alternate interpretations are sure to arise in the future. After all, Triceratops forelimb posture isn’t just an esoteric bit of anatomical trivia: it has major implications for the speed and athleticism of an extremely successful keystone herbivore. Understanding the limitations on this animal’s movement and behavior can contribute to our understanding of the ecosystem and environmental pressures in late Cretaceous North America. As such, I am eagerly awaiting the next round in this 100-plus year investigation.

A big thank you to Rebecca Hunt-Foster and Ralph Chapman for sharing their time and expertise while I was writing this post!

References

Chapman, R. Personal communication.

Chapman, R., Andersen, A., Breithaupt, B.H. and Matthews, N.A. 2012. Technology and the Study of Dinosaurs. The Complete Dinosaur, 2nd Edition. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Fujiwara, S. and Hutchinson, J.R. 2012. Elbow Joint Adductor Movement Arm as an Indicator of Forelimb Posture in Extinct Quadrupedal Tetrapods. Proceedings of the Royal Society 279: 2561-2570.

Hunt-Foster, R. Personal communication.

Paul, G.S. and Christiansen, P. 2000. Forelimb Posture in Neoceratopsian Dinosaurs: Implications for Gait and Locomotion. Paleobiology 26:3:450-465.