Spending a day at the American Museum of Natural History is always a joy. Particularly in its fourth floor fossil halls, AMNH stands head and shoulders above peer museums in the sheer breadth of collections on display. Something in the ballpark of 600 fossil vertebrate specimens are included, including no less than 135 mounted skeletons. Many of these represent taxa that cannot be seen anywhere else in North America. With each visit, however, I feel more and more that the AMNH fossil halls are showing their age. This is not surprising—the current exhibition opened in stages between 1994 and 1996. Strange as it seems to aging millennials like myself, that was 30 years ago. By comparison, the prior iteration of the fossil halls was completed in 1956, and was 31 years old when renovation planning began in 1987.

In their time, the current fossil halls were a monumental accomplishment—taking nine years to complete and costing $44 million (which would be more than $90 million today). Steering the ship was Lowell Dingus, a paleontologist by training who assumed the role of Project Director for the renovation. Dingus led a twenty-person team of AMNH researchers, writers, and preparators dedicated to the project, and Ralph Appelbaum Associates was hired to design a new look for the halls.

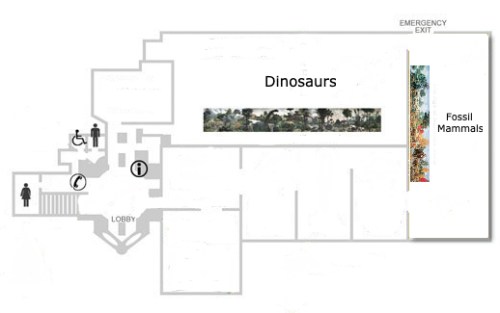

Initially, the intention was to only replace the two oldest halls, which featured Cenozoic mammal fossils. Some of these displays had not been altered since the 1920s, and others were boarded over because so many specimens had been removed for study or conservation. But when George Langdon and William Moynihan took over museum leadership positions, they decided to expand the project to include the two dinosaur halls. With the further addition of a new Hall of Vertebrate Origins (in a space previously occupied by the library) and a fourth floor Orientation Center, the project rapidly ballooned to cover 40,000 square feet of exhibit space and the entire story of vertebrate evolution.

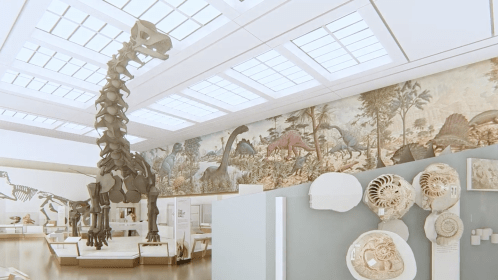

On the design side, the team sought to restore the original architecture in each hall, ensuring that both the specimens and the spaces they occupied would come, as Dingus put it, “as close to their original grandeur as possible.” In many cases, century-old architectural elements—such as windows and molded ceilings—were still intact behind panels that had been installed over them during previous renovations. These features were painstakingly restored, or when necessary, recreated. Classic decorative elements, from the colonnades to the elegant chandeliers, were reintroduced.

Dingus also had transformative plans for the fourth floor’s interpretation and organization. Rather than the traditional walk through time that characterized the midcentury exhibits, the renovated halls would be arranged according to phylogenetic classification: visitors were meant to explore the vertebrate family tree as they moved through the fourth floor galleries. Each large hall represented a major branch, and was further divided into smaller alcoves representing specific groups, like turtles, artiodactyls, or ornithomimid dinosaurs.

While this organization closely matched how paleontologists think about life on Earth (particularly those at AMNH who helped pioneer the cladistic methodology), it is unfamiliar to most visitors. For Dingus and his colleagues, this wasn’t a flaw—it was the point. “Is it enough simply to discuss what visitors want to know about,” Dingus wrote at the time, “or do exhibitions have a responsibility to broaden their audiences’ horizons by presenting challenging information?”

Dingus was planting a big, blue AMNH flag on one side of an ongoing debate about the role of museums and the purpose of their exhibits. “There is a prominent, contemporary school of exhibition design that advocates giving the visitor only what he or she asks for,” he wrote. “I vehemently disagree with this philosophy. We cannot pitch all the information to the lowest common denominator of interest and intellect.”

Dingus was likely referring to the philosophy championed by Michael Spock, who was at that time the Vice President for Public Programming at the Field Museum of Natural History. Spock had previously gained industry attention for his exploratory, interactive exhibitions at the Boston Children’s Museum. At the Field Museum, his approach was to make exhibitions “for someone, rather than about something.” Under Spock, projects began by asking community members what they were curious about, rather then by dictating what was important. Spock-era exhibits were filled with interactive and touchable displays meant to illustrate scientific concepts—some more successfully than others. They also tended to embrace a “less is more” aesthetic, taking deep dives into a few examples rather than trying to represent the full breadth of the museum’s collection.

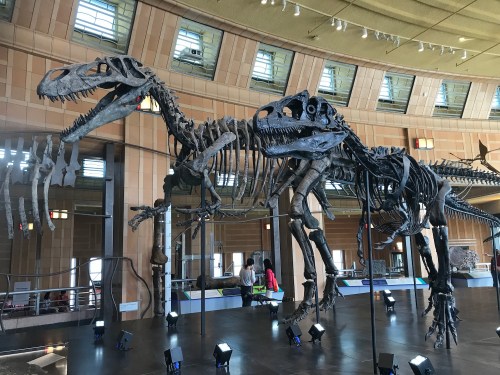

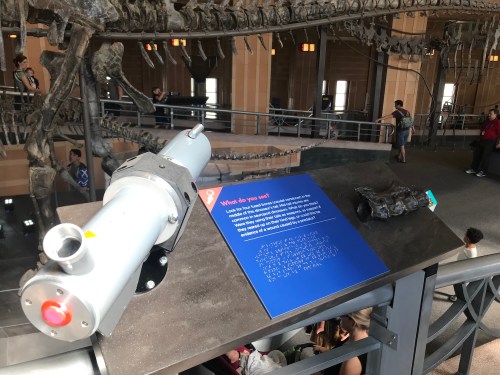

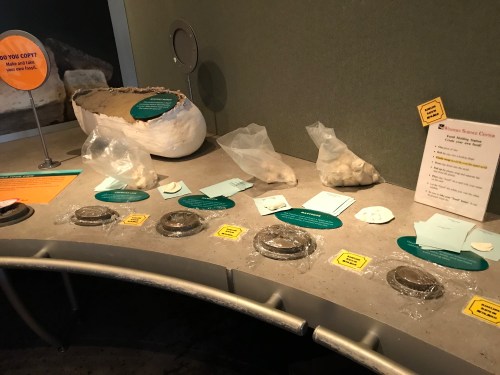

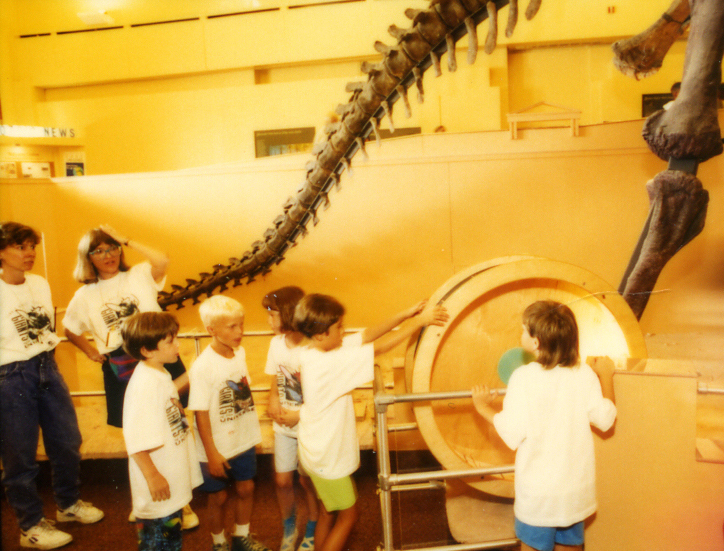

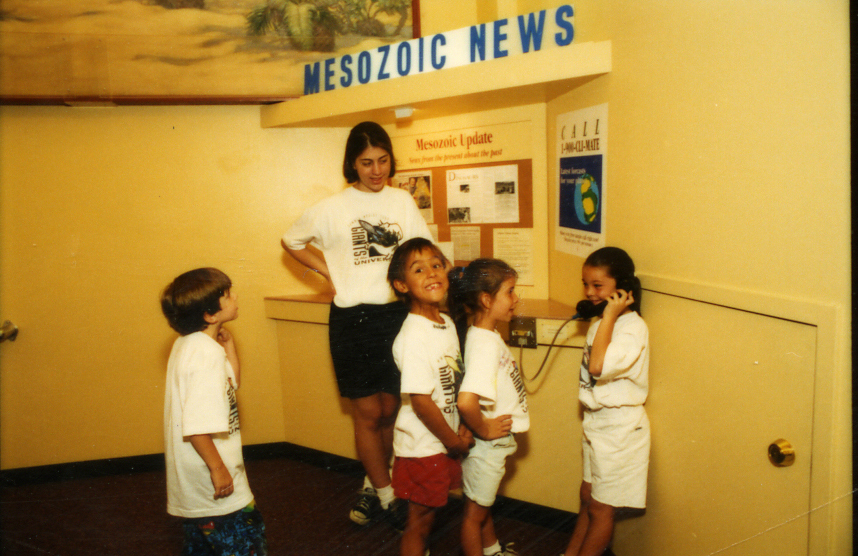

For better or worse, Dingus’s fossil halls at AMNH could not be more different than the ones Spock oversaw at the Field Museum. There are no levers to pull, no “Dial-a-Dinosaur” phones, and certainly no rideable trilobites (all features of the early 90s Field Museum). Instead, the focus is on the fossils, and—as mentioned—there are far more of them on display than at any comparable museum. The closest things to interactives are the computer terminals, which allow visitors to select from menus of scientist-narrated videos.

As it happened, Spock’s version of the Field Museum fossil halls barley lasted a decade, while Dingus’s AMNH exhibits remain mostly unchanged today: aside from the Patagotitan in the Orientation Center, the next largest addition might be a Tiktaalik cast skull in one case in the Hall of Vertebrate Origins. So how have the AMNH halls fared?

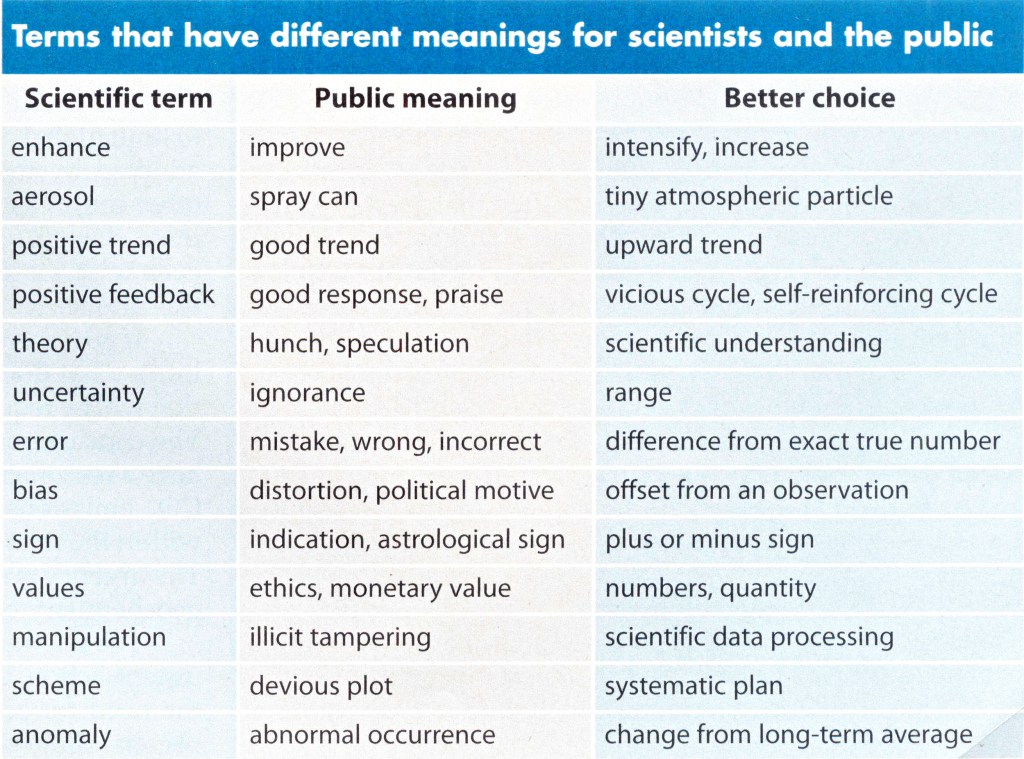

I sympathize with Dingus’s aim to “promote science literacy and develop a better awareness of how science can help illuminate the world.” That said, the AMNH fossil halls are clear example of a debunked educational style known as the “deficit model”—briefly, this is an approach to teaching that assumes students are empty vessels that can be simply filled with information. Moreover, I’m not convinced that the phylogenetic arrangement of the halls is particularly helpful for most visitors. The AMNH fossil halls are perfect for college students already learning about the diversity of life. But for most everyone else, the organization is opaque at best and a hindrance to understanding at worst. Making sense of phylogeny requires a lot of groundwork up front—even something as basic as knowing which direction to read a tree is not common knowledge. The Meryl Streep-narrated video in the Orientation Hall attempts to bridge this gap, but it’s overlong and not terribly engaging. Meanwhile, the multi-entrance, cyclical shape of the fourth floor means that only a fraction of visitors are actually starting in the Orientation Hall.

Within the galleries, the central pillars that update visitors on where they are in the tree are generally ignored. Part of the problem is that displays which highlight the three-fingered hand, the stirrup-shaped stapes, and other seemingly minor features that unify evolutionary groups are not especially compelling. And although I appreciate the wide open and well-lit spaces, I think the design of the halls might be working against the interpretation. It’s hard to tell where one grouping ends and another begins when every surface is either white or made of glass.

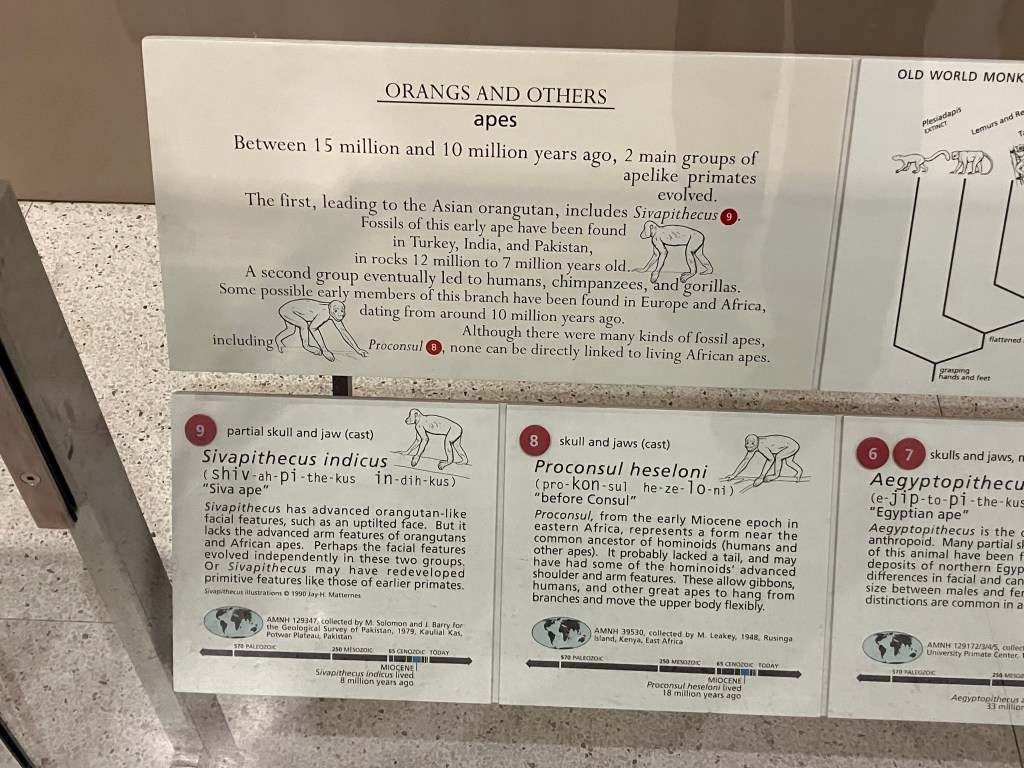

Speaking of unhelpful design, there are some bewildering graphic design choices in these halls. On a single graphic, text may switch from center to left to right justification, randomly change in font and/or size, or be interrupted by illustrations placed in the middle of paragraphs. Sometimes paragraphs or even sentences run across multiple surfaces, and some text is printed on the glass barriers in front of fossils, making it even harder to read. I don’t want to harp on this forever so I’ll just link to some more chaotic examples here, here, here, and here.

Simply put, I’d be very surprised if many visitors are engaging with the phylogenetic organization, or even wondering why the fossils they’re looking at are displayed together. Remember: most visitors come in mixed-aged groups. The trip to the museum is a social experience, and interactions occur among visitors as much as they occur between visitors and the exhibits. The best museums anticipate and meet the needs of these visitors. Too much information, or irrelevant information, is just as bad as too little. I’m all for “broadening horizons” with “challenging” content, but the exhibit needs to be accessible first.

Even if the AMNH fossil halls are pitched above most visitors’ levels of interest, background knowledge, and patience, is the information at least reliable? Much of it is, but phylogeny is inherently volatile, and many groupings (to say nothing of particular genera and species) in the exhibit have been out of date for decades. Visitors in 2024 are being told that tyrannosaurs are a kind of carnosaur (they’re actually coelurosaurs), that pangolins, aardvarks, and sloths form a group called Edentates (they’re actually distantly related), and that primates and rodents are closely related to bats (they’re not). But other groupings in these halls have fared better: the exhibition definitively states that birds are a kind of dinosaur, an idea that enjoys near-universal acceptance today but was reasonably disputable in the early 90s.

On top of the outdated information scattered throughout the halls, about a dozen of the mounted dinosaur skeletons are in old-fashioned, tail-dragging poses. These were known to be inaccurate at the time of the last renovation, but the budget only covered remounting two of them (the Apatosaurus and the Tyrannosaurus).

And just to be exhaustive in covering issues with the existing halls, many paleontologists over the years have discovered that the museum has no easy way to open the large glass cases that house some of AMNH’s most unique and significant fossils. Specimens like the Barosaurus, the Gorgosaurus pair, and the Corythosaurus mummy can only be accessed with the help of hired glaziers, and the museum requires scientists to cover the expense. This is well beyond most research budgets, and as a result, many of these world-famous and one-of-a-kind specimens have not been studied closely in decades.

So it’s fair to ask, why haven’t the AMNH fossil halls been updated yet? To be clear, the museum’s scientific and exhibitions staff are fully aware of everything I mentioned above. I’m sure the biggest hurdle is that a thorough renovation would be really, really expensive. For comparison, the NMNH renovation that took place between 2014 and 2019 cost $110 million ($70 million to restore the century-old east wing and $40 million for the exhibition itself). There’s also the cost in visitation to consider: if AMNH is anything like its peers, a big part of its operating budget comes from visitor admissions (for readers outside the United States, most of our museums are private nonprofits and do not get direct government support). Take away the most popular exhibition in the building for any length of time, and that income drops sharply.

From context clues, I don’t think a top-to-bottom renovation of the permanent fossil halls is coming any time soon. AMNH only recently hired a new fossil reptile curator, Roger Benson, in 2023. And the museum just opened a brand-new wing called the Gilder Center, which took five years and $465 million to build. The museum also just announced that it has temporary custody of Apex, a privately-owned Stegosaurus skeleton. According to a press release, Apex will eventually be the centerpiece of a new passageway connecting the Gilder Center to the permanent fossil halls (the real skeleton until 2028 or so, then a cast). I’d be surprised if we hear anything about a full-scale renovation until after Apex has left the building.

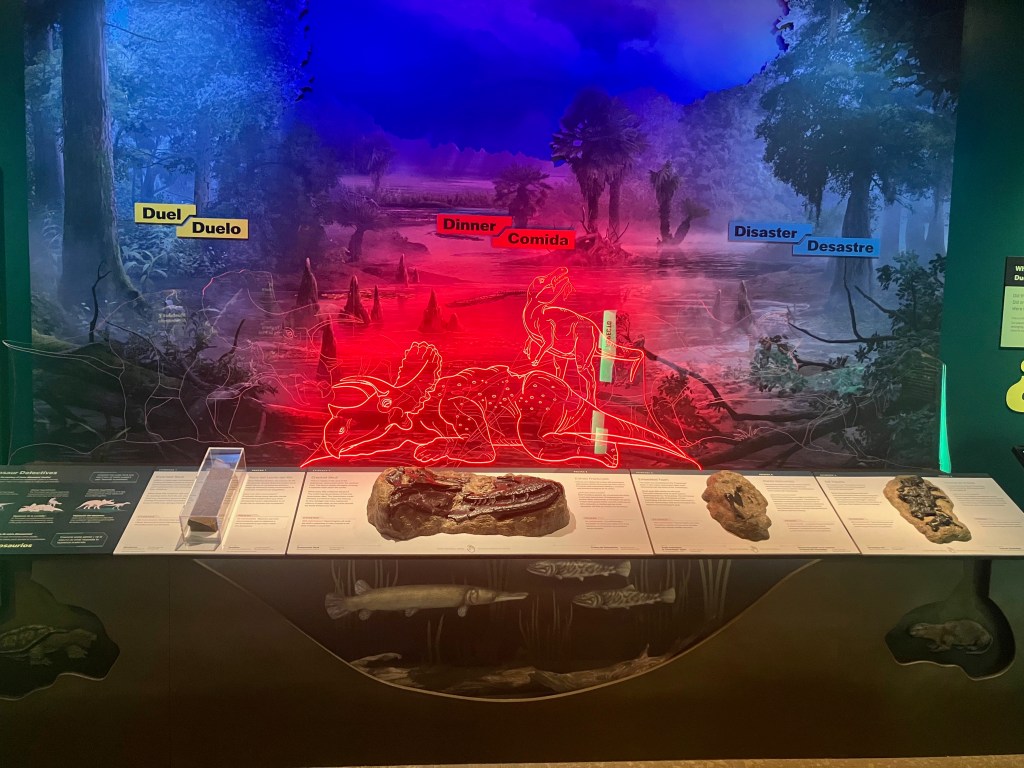

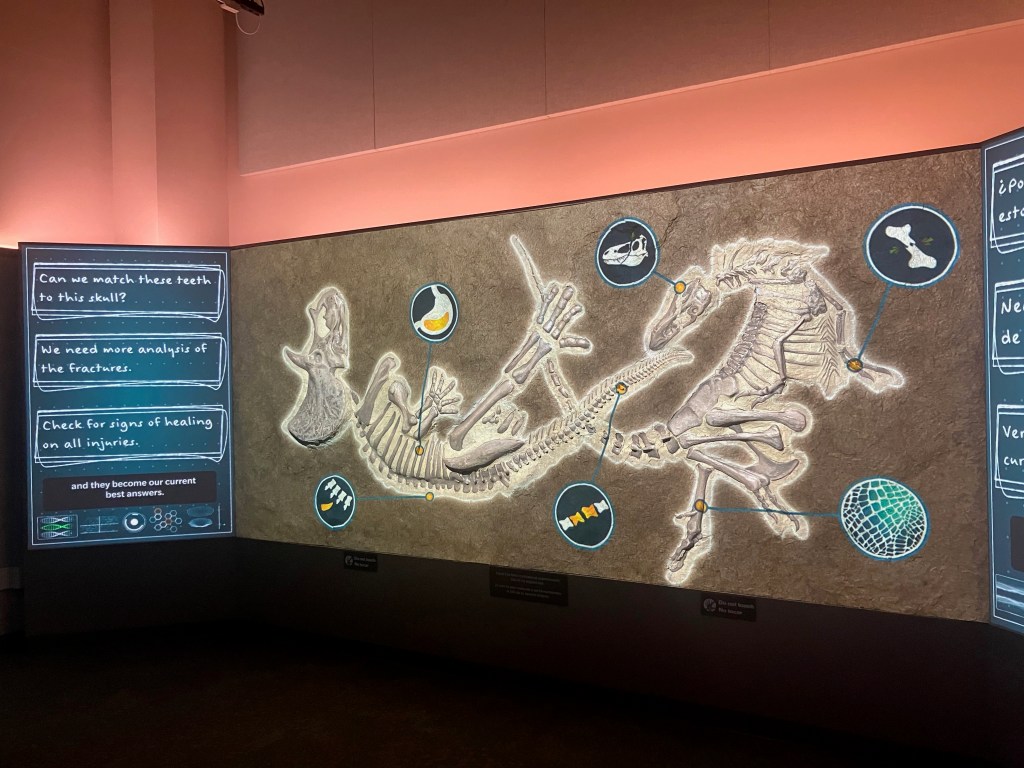

To their credit, the AMNH exhibitions team hasn’t exactly been idle when it comes to dinosaur displays. Over the last two decades, they’ve been rolling out a series of fossil-centric traveling exhibitions, including The World’s Largest Dinosaurs, Dinosaurs Among Us, Extreme Mammals, and T. rex: The Ultimate Predator. Each of these temporary shows has been up-to-date with new science and high-tech exhibtry. When the time comes, I’m sure this team could do great work on new permanent fossil galleries.

But for now, what are your hopes for the eventual AMNH renovation? What do you want to see changed or introduced? What should stay the same? Please leave a comment with your ideas!

References

Dingus, L. 1996. Next of Kin: Great Fossils at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Honan, W.H. 1990. Say Goodbye to the Stuffed Elephants. The New York Times Magazine.

Solomon, D. 1999. He Turns the Past Into Stories, and the Galleries Fill Up. The New York Times.

Spiegel, A.N., Evans, E.M., Frazier, B., Hazel, A., Tare, M., Gram, W., and Diamond, J. 2012. Changing Museum Visitors’ Conceptions of Evolution. Evolution: Education and Outreach 5:1:43-61.

Torrens, E. and Barahona, A. 2012. Why are Some Evolutionary Trees in Natural History Museums Prone to Being Misinterpreted? Evolution: Education and Outreach 1-25.