After I posted my slightly critical evaluation of the AMNH fossil halls last month, a reader suggested I take a look at Next of Kin by Lowell Dingus. Dr. Dingus was the project director for the 1995 renovation, and his book chronicles the decade-long process of overhauling these genre-defining exhibits. It also includes plenty of gorgeous photos of the AMNH fossil exhibits past and present. Although out of print, Next of Kin can be found online for next to nothing. If you find anything on this blog interesting, I would call this book required reading. I cannot recommend it enough.

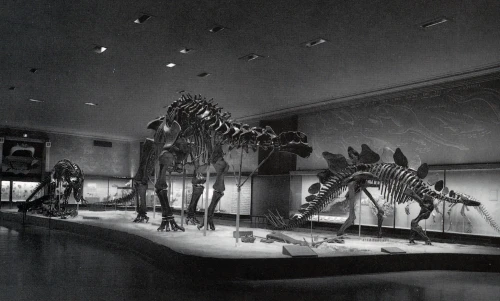

Edwin Colbert designed this version of the Jurassic exhibit in 1956. This space is now the Hall of Saurichian Dinosaurs. Photo from Dingus 1996.

Next of Kin is full of fascinating information about the renovation, and the history of the halls in general. For instance, it was news to me that the original plan in 1987 was to modernize only the two fossil mammal halls. When William Moynihan took over as Director of AMNH the following year, however, he asked in a planning meeting why the dinosaur exhibits weren’t being renovated, and soon the project expanded to include all six halls on the 4th floor. Apparently the approaches to interpretation, aesthetics, and layout that characterize the exhibits today were already fully formed. The concept of a main pathway with branching alcoves representing individual clades was in place, so the exhibit team only needed to set the starting point back a ways to include the dinosaurs and the rest of the vertebrate family tree. Restoring the historic interior architecture, obscured since the 1950s, was also an early priority. Dingus relates how he wanted to eliminate the “black box” look of the midcentury exhibits and let natural light back into the halls. In my opinion, the well-lit, airy aesthetic is one of the standout features of the AMNH fossil halls, and one other museums might do well to emulate.

Dingus also points out a number of clever design choices that I missed during my last visit to the museum. For instance, the primate section was deliberately placed in the center of the mammal hall, to avoid the implications of directed evolution and human superiority that once marked the AMNH exhibits. Another cool feature is the use of minimalist metal armatures to suggest the size and shape of animals for which only limited material is available. This is an artful way to convey the dimensions of these species without resorting to fabricating most of the skeleton. Again, this is something I’d love to see more of at other museums.

Still, I was most interested in reading Dingus’s rationale for the design and layout of the AMNH fossil halls. In my previous post, I argued that the phylogenetic arrangement was a worthwhile experiment, but in practice it may not be the most practical way to make the history of life meaningful to the museum’s primary audience. More than any other organizational scheme, phylogeny is the way biologists think about the natural world, and I applaud the effort to encourage visitors to look at fossils the way scientists do. However, even the most basic elements of evolutionary classification are specialized knowledge, and require a daunting amount of up-front explanation (especially when targeting multiple age groups). I don’t think this integrates well with the multi-entrance, non-linear exhibit space at AMNH.

During the initial planning stages of the AMNH renovation, Dingus and other staff toured several large-scale paleontology exhibits in North America and Europe. Dingus clearly did not like what he saw, lamenting that “some institutions rely heavily on easy-to-understand, anecdotal labels and robotic recreations of dinosaurs that appeal to the lowest common denominator of visitor intellect.” He rejected the “prominent contemporary school of exhibit design that advocates only giving the visitor what he or she asks for,” feeling strongly that his institution could do better. Referring to the renovation as a “scientific crusade,” Dingus was inspired to challenge his audience in a way that peer institutions did not. Dingus and his colleagues wanted to show visitors the real science behind paleontological reconstructions. The phylogeny-based arrangement was central to that goal, emphasizing rigorous anatomical analysis and empiricism in a field historically characterized by idle speculation.

The orientation hall is in the oldest of the 4th floor exhibit spaces. Until the 1960s, this space was occupied by the Hall of the Age of Man. Photo from Dingus 1996.

I agree wholeheartedly with all of this. There was a period in the 80s and 90s (I think the worst is behind us) when the trend toward visitor-focused, educational exhibits got mixed up with a push to make museums more competitive with other leisure activities. Customer enjoyment was valued above all else, even if it meant sacrificing the informative content and access to real specimens that made museums worthwhile institutions in the first place. The resulting displays were filled with paltry nonsense like simulators, pointless computer terminals, and the aforementioned robot dinosaurs*. These exhibits imitated amusement parks, but with only a fraction of the budget they quickly fell into disrepair and technological obsolescence. Despite being museums’ most important and unique resources, curators and research staff found themselves increasingly divorced from their institutions’ public faces.

*Fine, I admit robot dinosaurs are cool. But I’d prefer that they weren’t in museums.

Under these circumstances, a backlash is quite understandable. Nevertheless, it is a common mistake (which I am by no means accusing Dingus of making!) that a visitor-centered exhibit is the same as a frivolous one. When educators push for audience-focused exhibits, they have the same goal as curators: to communicate as much content as possible. Audience-focused exhibits aren’t about dumbing down or eliminating content. They’re about presenting content in a way that effectively reaches the museum’s diverse audience. The AMNH fossil halls would work well for an informed adult visitor with ample time to inspect every specimen and read every label. But this is not the typical audience for natural history museums, and unless AMNH is a major outlier, it’s not the core audience for these exhibits. Most visitors come in mixed-aged groups. The trip to the museum is a social experience, and interactions occur among visitors as much as they occur between visitors and the exhibits. The best museums anticipate and meet the needs of these visitors in order to provide a quality learning experience.

An updated version of the classic (and classically misleading) horse evolution exhibit. Photo by the author.

It’s admittedly fun to share horror stories about dumb comments overheard in museums. Who in this field hasn’t rolled their eyes at the parent who makes up an answer to their child’s question, when the correct information is on the sign right in front of them? And yet, some of the blame for this failed educational encounter should fall on the museum. Why was that parent unable to spot the relevant information with a quick glace? Can we design signage so that the most important information is legible on the move, or from across the room? Can we correct commonly misunderstood concepts in intuitive ways?

As Dingus argues, it’s important to aim high in the amount of information we want to convey. There’s nothing worse than a condescending teacher. But a carefully-honed message in common language will always be more successful than a textbook on the wall. Happily, this is the way the wind is blowing these days. In a strong reversal of the situation a decade ago, curators now work closely with educators on the front lines to produce exhibits that are both accessible and intellectually challenging. It’s been 20 years since AMNH opened the latest version of its fossil exhibits…perhaps a new and even better iteration is already on its way!

Reference

Dingus, L. (1996). Next of Kin: Great Fossils at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.