Who needs subtlety when you have a T. rex?

Start with Displaying the Tyrant King Part 1 and Part 2.

Tyrannosaurus rex displays changed for good in the 1990s thanks to two individuals, one real and one fictional. The latter was of course the T. rex from the film Jurassic Park, brought to life with a full-sized hydraulic puppet, game-changing computer animation, and the inspired use of a baby elephant’s screeching cry for the dinosaur’s roar. The film made T. rex real – a breathing, snorting, drooling animal unlike anything audiences had ever seen. Jurassic Park was a tough act to follow, and in one way or another, every subsequent museum display of the tyrant king has had to contend with the shadow cast by the film’s iconic star.

The other dinosaur of the decade was Sue, who scarcely requires introduction. First and foremost, Sue is the most complete Tyrannosaurus ever found, with 80% of the skeleton intact. Approximately 28 years old at the time of her death, Sue is also the eldest T. rex known, as well as one of the largest. The specimen’s completeness and exquisite preservation has allowed paleontologists to ascertain an unprecedented amount of information about the lifestyle of meat-eating dinosaurs. In particular, Sue’s skeleton is riddled with fractured and arthritic bones, as well as evidence of gout and parasitic infection that together paint a dramatic picture of the rough-and-tumble world of the late Cretaceous.

From South Dakota to Chicago

Cast of Sue at Walt Disney World, Orlando. Source

It was the events of Sue’s second life, however, that made her the fossil the world knows by name. Sue was discovered in the late summer of 1990 by avocational fossil hunter Susan Hendrickson (for whom the specimen is named) on the Cheyenne River reservation in South Dakota. Peter Larson of the Black Hills Institute, a commercial outfit that specializes in excavating, preparing, and exhibiting fossils, initially intended to display the Tyrannosaurus at a new facility in Hill City, but soon became embroiled in an ugly four-way legal battle with landowner Maurice Williams, the Cheyenne council, and the United States Department of the Interior. With little precedent for ownership disputes over fossils, it took until 1995 for the District Court to award Williams the skeleton. Williams soon announced that he would put Sue on the auction block, and paleontologists initially worried that the priceless specimen would disappear into the hands of a wealthy collector, or end up in a crass display at a Las Vegas casino. Those fears were put to rest in 1997 when Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History won Sue with financial backing from McDonald’s and Disney. Including the auctioneer’s commission, the price was an astounding $8.36 million.

FMNH and its corporate partners did not pay seven figures for Sue solely to learn about dinosaur pathology. Sue’s remarkable completeness would be a boon to scientists, but her star power was at least as important for the Museum. Sue was a blockbuster attraction that would bring visitors in the door, and her name and likeness could be marketed for additional earned income. As FMNH President John McCarter explained, “we do dinosaurs…so that we can do fish” (quoted in Fiffer 2000). Particularly in the late 1990s, with Jurassic Park still fresh in people’s minds, a Tyrannosaurus would attract visitors and generate funds, which could in turn fund less sensational but equally important research, like ichthyology and entomology.

Still, some worried that McCarter, whose background was in business, not science, was exploiting an important specimen as a marketing gimmick at the expense of the Museum’s educational mission. This echoed similar concerns voiced 80 years earlier, when the original mounted Tyrannosaurus was introduced at the American Museum of Natural History. As president of AMNH, Henry Osborn oversaw the creation of grandiose and dramatic exhibits, with the intent to draw crowds and justify private and municipal financial support. When the Museum unveiled the Tyrannosaurus mount, Osborn held a lavish publicity gala for the New York elite and members of the press. The buzz generated by Osborn’s promotion resulted in lines around the block and front page headlines, but the attention was focused on the spectacle of the dinosaur rather than the science behind it. Many academics derided this as lowest common denominator pandering, while others, like anthropologist Franz Boas, grudgingly accepted that “it is a fond delusion of many museum officers that the attitude of the public is a more serious one, but the majority do not want anything beyond entertainment.”

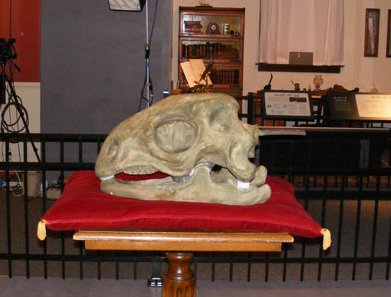

Original skull of Sue the T. rex, displayed on the upper mezzanine. Photo by the author.

FMNH was under similar scrutiny as museum staff revealed their plans for Sue. The role of the corporate sponsors that paid for the fossils was a particular cause for concern, and the marketing team knew it. Although the idea of T. rex-themed Happy Meals was briefly on the table, McDonald’s and Disney wisely opted to present themselves only as patrons of science. McDonald’s got its name on the new fossil preparation lab at FMNH and Disney got a mounted cast of Sue to display at Walt Disney World, but the principal benefit to the two companies was high-profile exposure in association with youth science education. The Museum retained control over the message, highlighting Sue’s importance to paleontology and only coyly admitting her role as a promotional tool. Likewise, FMNH is the sole profiteer from the litany of shirts, hats, toys, mugs, and assorted trinkets bearing the Sue name and logo that are continually sold at the Museum and around Chicago.

You May Approach Her Majesty

Once Sue arrived at FMNH, the Museum did not hold back marketing the dinosaur as a must-see attraction. A pair of Sue’s teeth went on display days after the auction, which expanded organically into the “Sue Uncrated” exhibit, where visitors could watch the plaster-wrapped bones being unpacked and inventoried. Meanwhile, McDonald’s prepared an educational packet on Sue that was distributed to 60,000 elementary schools.

The main event, of course, was the mounted skeleton, which needed to be ready by the summer of 2000. This was an alarmingly short timetable, and the FMNH team had to hit the ground running. Much of Sue’s skeleton was still buried in rock and plaster. The bones needed to be prepared and stabilized before they could be studied, and they needed to be studied before they could be mounted. In addition, two complete Sue casts had to be fabricated: one for Disney World and one for a McDonald’s-sponsored traveling exhibit. The casts were produced by Research Casting International, the Toronto-based company that recently built the mounted menagerie for “Ultimate Dinosaurs“. Phil Fraley Productions, the same exhibit company that rebuilt the American Museum and Carnegie Museum T. rex mounts, was tapped to mount Sue’s original skeleton.

The mounted skeleton of Sue in the Stanley Field Hall. Photo by the author.

Unlike every other Tyrannosaurus mount before or since, Sue can hardly be called a composite. With the exception of a missing arm, left foot, a couple ribs, and small number of other odds and ends, the mounted Sue skeleton is composed of real fossils from a single individual. FMNH public relations latched onto this fact, emphasizing in press releases that while “many museums are displaying replicas of dinosaur skeletons, the Field Museum has strengthened its commitment to authenticity. This is Sue.” Just as they did with the AMNH Tyrannosaurus, Fraley’s team built an armature with individual brackets securing each bone, allowing them to be removed with relative ease for research and conservation. No bolts were drilled into the bones and no permanent glue was applied, ensuring that the fossils incur only minimal damage for the sake of the exhibit. Despite these improvements over historic mount-making techniques, however, the Sue mount does have some inexplicable anatomical errors. The coracoids should be almost touching in the middle of the chest, but the shoulder girdles are mounted so high on the rib cage that there is a substantial space between them. Consequently, the furcula (wishbone) is also positioned incorrectly.

After a private event not unlike the one held by Osborn in 1915, Sue was revealed to the public on May 17, 2000 with the literal raising of a curtain. A week-long series of celebrations and press junkets introduced Sue to Chicago, and she has been one of the city’s biggest attractions every since. All the publicity paid off, at least in the short term: FMNH attendance soared that year from 1.6 million to 2.4 million. 14 years later, Sue the Tyrannosaurus is still known by name, and is even used as the voice of FMNH on twitter. Interestingly, Sue’s new identity as a Chicago landmark seems to have all but eclipsed the legal dispute that was her original source of fame. A recent RedEye cover story goes so far as to proclaim this South Dakotan skeleton as “pure Chicago.”

The Nation’s T. rex

This customized truck transported the Nation’s T. rex from Montana to Washington, DC.

This year, another Tyrannosaurus specimen has rocketed to Sue-like levels of notoriety. MOR 555, also known as “Wankel Rex”, is being transferred to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, where it will eventually be mounted for long-term display. Now dubbed “the Nation’s T. rex“, the promotion of this specimen has mirrored that of Sue in many ways. Front-page media coverage, first-person tweets from the dinosaur and even an official song and dance contest herald the arrival of the fossils from their previous repository, the Museum of the Rockies in Montana. Much like the “Sue Uncrated” exhibit, the process of unpacking the unarticulated bones will soon be on view in a temporary display called “The Rex Room.” Meanwhile, the very name “Nation’s T. rex” is a provocative invented identity akin to Sue’s new status as a Chicagoan.

Nevertheless, the Nation’s T. rex does not quite live up to Sue’s mystique. This Tyrannosaurus is neither as large nor as complete as Sue, and there was no prolonged legal battle or frantic auction in its past. The 60% complete skeleton was found in 1988 by Montana rancher Kathy Wankel, on land owned by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The fossils are now on a 50 year loan from from the Corps to the Smithsonian, (presumably) a straightforward transfer between federal agencies. In addition, MOR 555 is by no means a new specimen. Several casts of the skeleton are already on display, including exhibits at the Royal Ontario Museum, the Museum of the Rockies, the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, and even the Google campus. In fact, a cast of the MOR 555 skull has been on display at NMNH for years.

NMNH Director Kirk Johnson, fossil hunter Kathy Wankel, her husband Bob Wankel, and Lt. Gen. Thomas Bostick preside over the arrival of the Nation’s T. rex at the Smithsonian. Source

With that in mind, the hype around the Nation’s T. rex might seem like much ado about nothing. As this series has demonstrated, the number of Tyrannosaurus skeletons on exhibit, whether original fossils or casts, has exploded in recent years. A quarter century ago, New York and Pittsburgh were the only places where the world’s most famous dinosaur could be seen in person. Today, there may well be over a hundred Tyrannosaurus mounts worldwide, most of which are identical casts of a handful of specimens. Acquiring and displaying a T. rex is neither risky nor ambitious for a natural history museum. No audience research or focus groups are needed to know that the tyrant king will be a hit. And yet, excessive duplication of a sure thing might eventually lead to monotony and over-saturation.

So far, such fears appear to be unfounded. A specimen like Sue or the Nation’s T. rex is ideal for museums because it is at once scientifically informative and irresistibly captivating. Museums do not need to choose between education and entertainment because a Tyrannosaurus skeleton effectively does both. And even as ever more lifelike dinosaurs grace film screens, museums are still the symbolic home of T. rex. The iconic image associated with Tyrannosaurus is that of a mounted skeleton in a grand museum hall, just as it was when the dinosaur was introduced to the world nearly a century ago. The tyrant king is an ambassador to science that unfailingly excites audiences about the natural world, and museums are lucky to have it.

The Nation’s T. rex in its final pose at the Research Casting International workshop.

This week, NMNH will be celebrating all things Tyrannosaurus, starting with a live webcast of arrival of the Nation’s T. rex on Tuesday morning. Stay tuned to this blog for further coverage of the events!

References

Asma, S.T. 2001. Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Boas, F. 1907. Some Principles of Museum Administration. Science 25:650:931-933.

Counts, C.M. 2009. Spectacular Design in Museum Exhibitions. Curator 52: 3: 273-289.

Fiffer, S. 2000. Tyrannosaurus Sue: The Extraordinary Saga of the Largest, Most Fought Over T. rex ever Found. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Larson, N. 2008. “One Hundred Years of Tyrannosaurus rex: The Skeletons.” Tyrannosaurus rex: The Tyrant King. Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth, eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Lee, B.M. 2005. The Business of Dinosaurs: The Chicago Field Museum’s Nonprofit Enterprise. Unpublished thesis, George Washington University.

Rainger, R. 1991. An Agenda for Antiquity: Henry Fairfield Osborn and Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, 1980-1935. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

Switek, B. 2013. My Beloved Brontosaurus: On the Road with Old Bones, New Science and our Favorite Dinosaurs. New York, NY: Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.