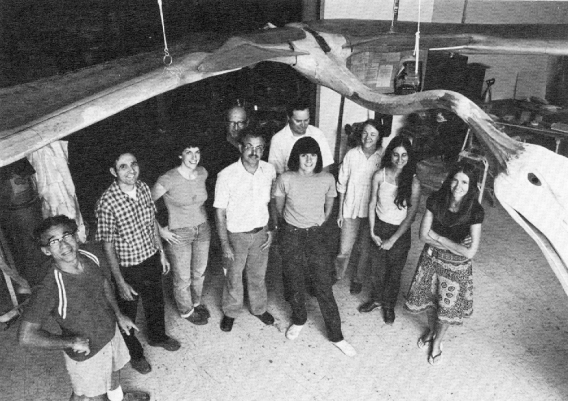

A revamp for the dinosaur displays in Hall 2. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Since the NMNH building opened in 1910 as the United States National Museum, the east wing has been home to fossil displays. Although there have been many small adjustments and additions to the exhibits over the years, we can separate the east wing’s layout into three main periods. From 1910 t0 1945, the exhibits were primarily under the stewardship of Charles Gilmore. Called the “Hall of Extinct Monsters”, this iteration was somewhat haphazard in its layout and generally resembled a classic “cabinet of curiosity” approach to exhibit design. Gilmore’s version of the east wing remained in place until 1963, when the space was redesigned as part of the Smithsonian-wide modernization project. In the updated halls, there was a directed effort to compartmentalize exhibits based on the subdivisions of the Museum’s research staff, with each area of the gallery becoming the responsibility of a different curator. A second renovation was carried out in several stages starting in 1980. This version, which was open until 2014, was part of the new museology wave that started in the late 1970s. As such, the exhibits form a more cohesive narrative of the history of life on earth, and much of the signage carries the voice of educators, rather than curators.

Of course, the field of paleontology has advanced by leaps and bounds since the early 1980s, and NMNH staff have made piecemeal updates to the galleries when possible, including restorations of deteriorating mounts, and additional signage that addresses the dinosaurian origin of birds and the importance of the fossil record for understanding climate change. A third renovation is currently underway and will be completed in 2019.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The purpose of this post is to provide an overview of the NMNH fossil halls as they stood in 1963, after the first major renovation. This iteration of the east wing was long gone before I was born, so this information is pieced together from historic photographs, archived exhibit scripts, and correspondence among the individuals involved in the modernization project (my thanks to the staff of the Smithsonian Institution Archives for their assistance in accessing these materials). Perhaps unsurprisingly, records of the dinosaur gallery are by far the most thorough. Information on the other halls is considerably harder to come by, so if any readers who saw the older exhibits in person remember any details, it would be fantastic if you could share them.

As mentioned, the Smithsonian underwent a thorough modernization project in the middle of the 20th century. The modernization committee, chaired by Frank Taylor (the eventual director-general of Smithsonian museums), was established in 1948. Under the committee’s guidance, most of the institution’s exhibits were redesigned between 1953 and 1963. Keep in mind that at the time, the United States National Museum was the only Smithsonian museum – it would not be divided into the National Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of History and Technology (now the National Museum of American History) until 1964.

Completed in 1963, the USNM fossil exhibits were among the last to be modernized. Only a small number of specimens were added that had not already been on view in the previous version of the space – in fact, many specimens were removed. The changes primarily focused on the layout of the exhibit, turning what was a loosely organized set of displays into a series of themed galleries. The east wing included four halls in 1963, the layout of which can be seen in the map above. Each hall was the responsibility of a particular curator. Nicholas Hotton oversaw Paleozoic and Mesozoic reptiles in Hall 2. David Dunkle was in charge of fossil fish in Hall 3. Porter Kier oversaw fossil invertebrates and plants in Hall 4. Finally, Charles Gazin, head curator of the Paleontology Division, was responsible for Cenozoic mammals in Hall 5. Each curator had a central role in selecting specimens for display and writing accompanying label copy.

Invertebrates and Fossil Plants

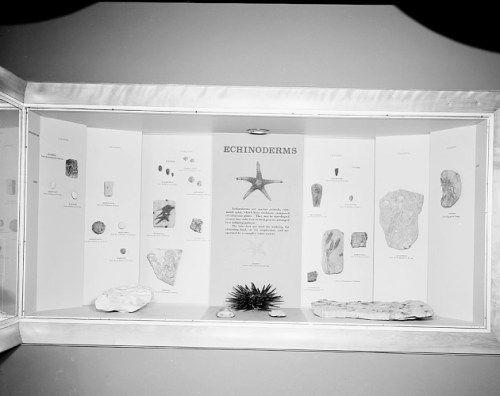

Echinoderm fossil display in Hall 4. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

It is likely that part of the reason the fossil halls were late on the modernization schedule was that the curators of the Paleontology Division were not terribly interested in exhibits or outreach. There were no staff members in the division exclusively devoted to exhibit work, so the task of designing the new exhibit space was an added burden for the research staff. As invertebrate paleontology curator G. Arthur Cooper put it in a 1950 memo, “all divisions of Geology at present are in an apathetic state toward exhibition.”

Nevertheless, work on the east wing halls had begun by 1957, if not a bit earlier. The first of the new exhibits to be worked on was Hall 4, featuring fossil invertebrates and plants. The long and narrow space was divided into four sections: the first introduced the study of fossils and how they are preserved, the second was devoted to paleobotany, the third contained terrestrial and marine invertebrates, and the forth provided an overview of geological time. Cooper described the new exhibit as a progressive story of the expansion of life, “its stem connecting all life which is now culminating in man.”

Carboniferous coal swamp fossils in Hall 4. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

In addition to a variety of fossil specimens, Hall 4 featured a series of dioramas built by George Merchand, an exhibit specialist from Ann Arbor, Michigan. Merchand built at least 4 dioramas between 1957 and 1958, each depicting representative invertebrate marine fauna from a different Paleozoic period. Most, if not all, of these dioramas were retained during the 1980s renovation and remained on view through 2014.

Fossil Fishes and Amphibians

Fossil fishes in Hall 3. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Fossil fish and a smattering of amphibians were located in Hall 3, on the far east side of the wing. This space would be converted into “Mammals in the Limelight” in the 1980s. David Dunkle, for whom everyone’s favorite placoderm Dunkleosteus is named, was in charge of this gallery during his tenure at USNM between 1946 and 1968. The specimens on view were arranged temporally, starting with placoderms on the south side and progressing into actinopterygians and basal amphibians on the north end. Among the more prominently displayed specimens were Xiphactinus, Seymouria, and “Buettneria” (=Koskinonodon). The hall also contained a replica of the recently discovered modern coelacanth, and small diorama of a Carboniferous coal swamp.

Dinosaurs and Other Reptiles

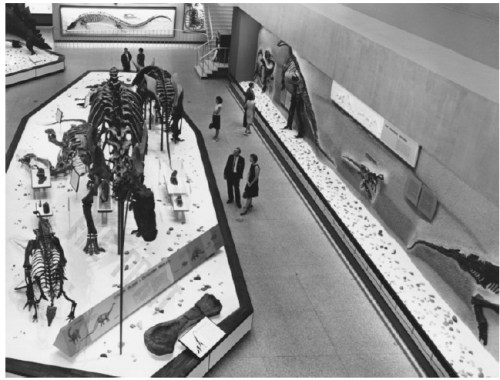

Dinosaurs in Hall 2, as seen facing west. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Hall 2, featuring dinosaurs and other reptiles, was the main draw for most visitors. It was not, however, a major priority for the Smithsonian research staff. The museum had not had a dinosaur specialist since Gilmore passed away in 1945 and indeed, dinosaurs were not an especially popular area of study among mid-century paleontologists in general. As such, responsibility for Hall 2 fell to Nicholas Hotton, at the time a brand-new Associate Curator. Later in his career, Hotton would be best known as an opponent to the dinosaur endothermy movement, but in the early 1960s he was most interested in early amniotes and the origin of mammals.

Hotton’s display of South African synapsids and amphibians. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

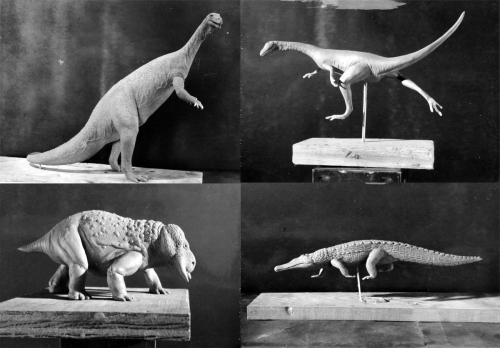

Perhaps due to the general disinterest among USNM curators, changes to the dinosaur exhibits were mostly organizational. Most of the free-standing dinosaur mounts built by Gilmore and his team were collected on a single central pedestal. Preferring not to tackle the massive undertaking of disassembling and remounting the 70-foot Diplodocus skeleton, the exhibit designers left the sauropod in place and clustered the smaller moutns around it. In the new arrangement, the Diplodocus was flanked by the two Camptosaurus and prone Camarasaurus on its right and by Triceratops and “Brachyceratops“ on its left. The Stegosaurus stenops holotype, splayed on its side in a recreation of how it was first discovered, was placed behind the sauropods at the back of the platform.

Close up of Thescelosaurus on the south wall. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

The north and south walls of Hall 2 were lined with additional specimens. On the south side, Gilmore’s relief mounts of Ceratosaurus and Edmontosaurus (called “Anatosaurus” in this exhibit) were joined by the gallery’s one new dinosaur, a relief mount of Gorgosaurus in a death pose. The north wall featured a long, narrow, glass-enclosed case illustrating the basics of dinosaur classification. In addition to saurischian and ornithischian pelves, the case featured skulls representing most of the major dinosaur groups. Amusingly, all but two of these skulls (Triceratops and Diplodocus) were labeled with names that are no longer considered valid. These skulls included “Antrodemus” (Allosaurus), “Trachodon” (Edmontosaurus) “Procheneosaurus” (probably Corythosaurus) and “Monoclonius” (Centrosaurus).

In the southwest corner of Hall 2 (where FossiLab is today), visitors could see the Museum’s two free-standing Stegosaurus: the fossil mount constructed by Gilmore in 1913 and the charmingly ugly papier mache version, which had received a fresh coat of paint. Finally, the rear (east) wall of Hall 2 held Gilmore’s relief mounted Tylosaurus.

Mammals

Brontotherium and Matternes’ Oligocene mural in Hall 5. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Fossil mammals were exhibited in Hall 5, a corridor-like space accessible from the main rotunda and via two doorways on the north side of Hall 2. After 1990, this space would house the “Life in the Ancient Seas” exhibit. Charles Gazin, head curator of the Division of Paleontology, was in charge of this space on paper, but my impression is that his attention was elsewhere during its design and construction. Gazin was apparently approached by the modernization committee several times during the 1950s, but was reluctant to commit his time to a major renovation project. Gazin had been spending a great deal of time at a Pliocene dig site in Panama, and the collection of new fossils proved more interesting than designing displays. As Gazin tersely explained, “It is a little difficult to concentrate objectively on exhibition problems here in the interior of Panama.”

Basilosaurus and Cenozoic reptiles in Hall 5. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Nevertheless, Gazin’s interest in Cenozoic mammals ensured that his gallery was exceptionally thorough. Thanks to Gazin’s own collecting expeditions throughout the 1950s, the new fossil mammals galleries contained representatives of nearly all major mammal groups, from every epoch from the Paleocene through the Pliocene (the Pleistocene was deliberately excluded, as a separate ice age exhibit was also in the works). Classic mounts from the Gilmore era like Basilosaurus and Teleoceras were joined by dozens of less showy specimens like rodents, small perissodactyls, and early primates. The new exhibit also introduced the first wave of Jay Matternes’ much-beloved murals, illustrating the changing flora and fauna in North America over the course of the Cenozoic.

Unveiling and Reactions

The new east wing galleries officially opened on June 25, 1963. According to the press release, “the new exhibit features in colorful and dramatic settings more than 24 skeletons and skulls of the largest land animals the world has ever known.” The exhibits were officially unveiled with a late afternoon ceremony, in which Carol Hotton (Nicholas Hotton’s daughter) cut the ribbon and the lights to Hall 2 were suddenly turned on to dramatic effect.

Unfortunately, the new exhibits were not universally loved by the museum staff. The wing had been planned a set of compartmentalized exhibits, each corresponding to a subdivision of the Division of Paleontology, with a different curator taking responsibility for each hall. While seeming sensible on paper, this plan turned out to be a logistical nightmare, and a common cause for complaint among Division staff for the next decade. In addition, Gazin in particular voiced concerns as early as January 1964 that the design of the new halls was entirely inadequate for preventing accidental or deliberate damage to specimens by visitors. The mounts in Hall 2 were raised only about a foot off the ground, and were not protected by any sort of guard rail or barrier. As a result, within a few months of the exhibit’s unveiling, several ribs and vertebral processes had been broken off or stolen from Camarasaurus, Gorgosaurus, Ceratosaurus and others.

With the notable caveat that I never saw the 1963 exhibits in person, I would say that this is aesthetically my least favorite iteration of the east wing. The grandiose, institutional Greco-Roman architecture originally displayed in the Hall of Extinct Monsters was replaced with what can only be described as extremely 1960s design. Solid earth-tone colors, wood paneling and wall-to-wall carpeting gave the halls a much more austere character. While the efforts to categorize specimens into thematic zones was commendable for a museum of that era, the label copy (written by the curators) was still highly pedantic and verbose. As such, the 1963 fossil halls seem to have been very much of their time. While the designers were working to avoid the overt religiosity and grandeur of turn of the century museums, they had not yet reached the point of developing truly audience-centered educational experiences. The result was an exhibit that was humble, yet still largely inacessible. Perhaps for this reason, the 1963 fossil halls were the shortest-lived at NMNH to date, being replaced within 20 years of their debut.

This post was updated and edited on January 8, 2018.