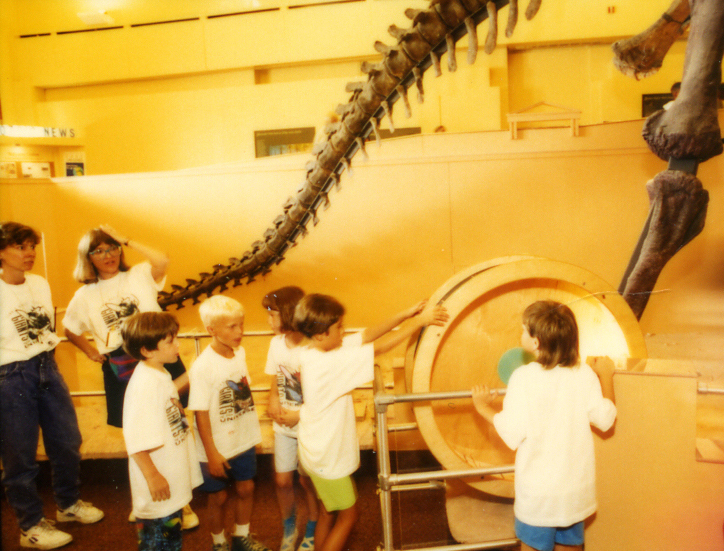

This is an updated version of a series of posts from 2014. With Deep Time and the new SUE exhibition now open, I’m dusting it off and bringing it up to date.

Woodrow Wilson is in the white house. The first World War is raging in Europe, but the United States is not yet involved. The women’s suffrage movement is picking up speed. And you just heard that the skeleton of an actual dragon is on display at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. It is difficult to imagine a time before Tyrannosaurus rex was a household name, but such was the case barely a century ago. In 1915, AMNH unveiled the very first mounted skeleton of the tyrant lizard king, immediately and irrevocably cementing the image of the towering reptilian carnivore in the popular psyche.

Today, Tyrannosaurus is a celebrity among dinosaurs, appearing in every form of media imaginable. More importantly, it is an icon for paleontology and an ambassador to science. Much has been written about T. rex — about its discovery, about the animal itself, and about its role in popular culture. This article will take a slightly different tack. This is an overview of the history of the tyrant king on display, and how it has defined (and been defined by) the museum experience.

The cult of T. rex began in the halls of museums, and museums remain the prehistoric carnivore’s symbolic home. Mounted skeletons provide the legendary T. rex its credibility: these are the authentic remains of the giant predator that once stalked North America. And yet, most of the dozens of Tyrannosaurus skeletons on display around the world are casts, and none of them represent complete skeletons (rather, they are filled in with spare parts from other specimens and the occasional sculpted bone). These are sculptures as well as scientific specimens, works of installation art created by artists, engineers, and scientists. Herein lies the paradox presented by all fossil mounts: they are natural specimens and constructed objects, embodying a challenging duality between the realms of empiricism and imagination.

I. The Original Tyrant

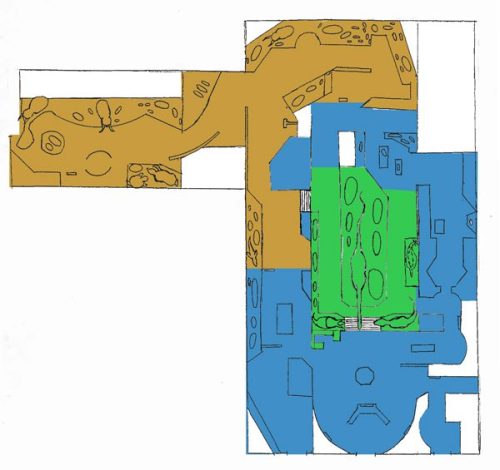

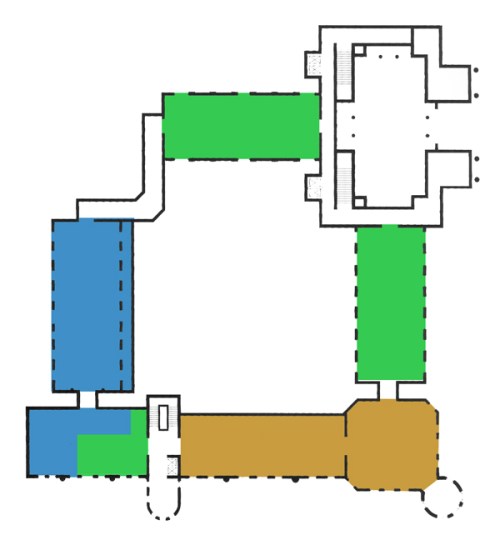

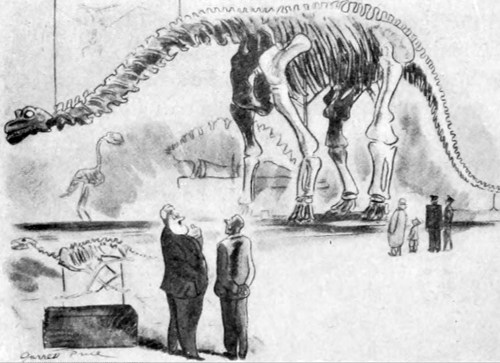

Between 1890 and 1910, the United States’ natural history museums entered into a frenzied competition to find and display the largest and most spectacular dinosaur skeletons. Although discoveries by paleontologists like O.C. Marsh and E.D. Cope in the late 19th century fleshed out the scientific understanding of Mesozoic reptiles, it was these turn-of-the-century museum displays that brought dinosaurs into the public sphere. Bankrolled by New York’s wealthy aristocrats and led by the ambitious (and extremely problematic—read on) Henry Osborn, the American Museum of Natural History won the fossil race by most any measure. The New York museum completed the world’s first mounted skeleton of a sauropod dinosaur in 1905, and also left its peer institutions in the dust with the highest visitation and the most fossil mounts on display.

Osborn’s goal was to establish AMNH as the global epicenter for paleontology research and education, and in 1905 he revealed his ace in the hole: two partial skeletons of giant meat-eating dinosaurs uncovered by fossil hunter Barnum Brown. In a deceptively brief paper in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, Osborn described the fossils from Wyoming and Montana, coining the names Dynamosaurus imperiosus and Tyrannosaurus rex (a follow-up paper in 1906 reclassified “Dynamosaurus” as a second Tyrannosaurus specimen). Fully aware of what a unique prize he had in his possession, Osborn wasted no time leveraging the fossils for academic glory. He placed the unarticulated bones on display shortly after his initial publication, and commissioned artist Charles Knight to prepare a painting of the animal’s life appearance.

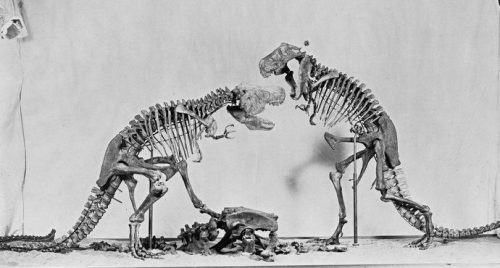

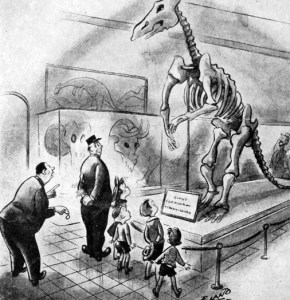

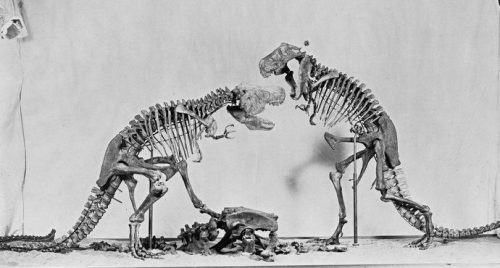

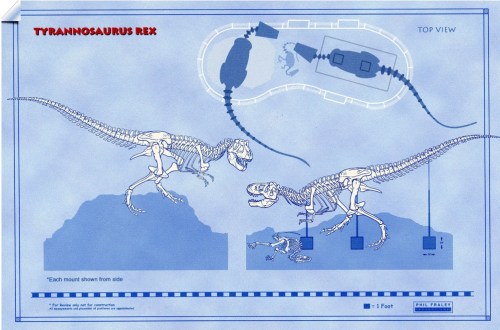

E.S. Christman’s miniature models act out Osborn’s unrealized battling Tyrannosaurus display. Image courtesy of the AMNH Research Library.

In 1908, Brown collected a much more complete Tyrannosaurus specimen (AMNH 5027), with over 50% of the skeleton intact, including the first complete skull and a significant portion of the torso. With this specimen in hand, AMNH technician Adam Hermann and his team began work on a mounted Tyrannosaurus skeleton to join the Museum’s growing menagerie of dinosaurs and prehistoric mammals. Inspired by the museum’s habitat dioramas and seeking to accentuate the spectacle of his reptilian monster, Osborn initially wanted to mount two Tyrannosaurus skeletons facing off over a dead hadrosaur. He even published a brief description, complete with 1/10th scale wooden models illustrating the proposed exhibit (above). However, the structural limitations inherent to securing heavy fossils to a steel armature, as well as the inadequate amount of Tyrannosaurus fossils available, made such a sensational display impossible to achieve.

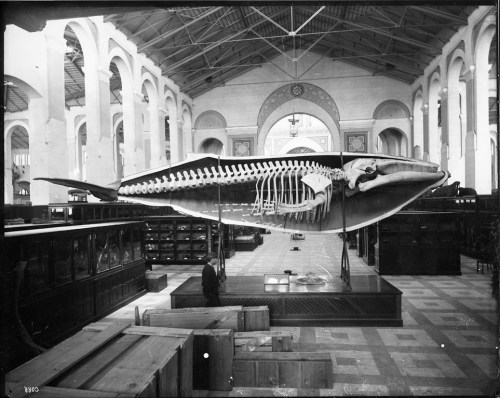

Instead, Hermann prepared a single Tyrannosaurus mount, combining the 1908 specimen with plaster casts of the hips and femur from the 1905 holotype. The original skull was impractically heavy, so a cast was used in its place. Missing portions of the skeleton, including the arms, feet, and most of the tail, were sculpted by hand using bones from Allosaurus as reference. During the early 20th century, constructing fossil mounts was a relatively new art form, and while Hermann was one of the most talented and prolific mount-makers around, his techniques were somewhat unkind to the fossil material. Bolts were drilled directly into the fragile bones to secure them to the armature, and in some cases steel rods were tunneled right through them. Any fractures were sealed with plaster, and reconstructed portions were painted to be nearly indistinguishable from the original fossils. Like most of the early AMNH fossil mounts, preserving the integrity of the Tyrannosaurus bones was secondary to aesthetic concerns like concealing the unsightly armature.

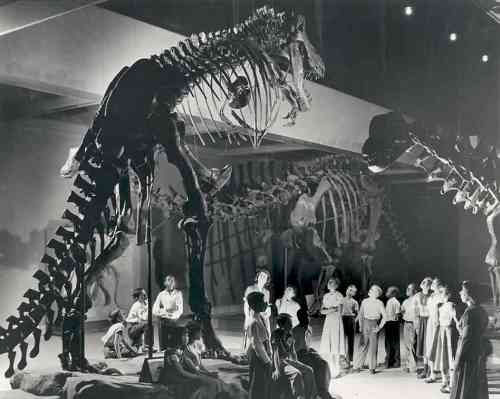

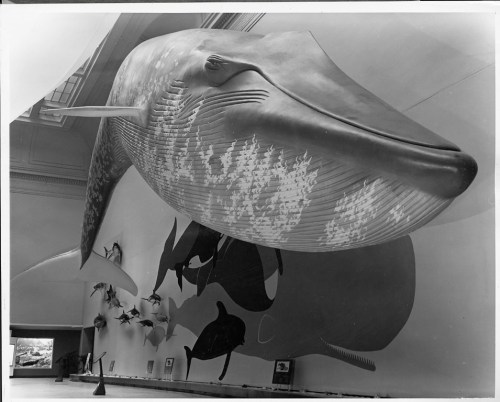

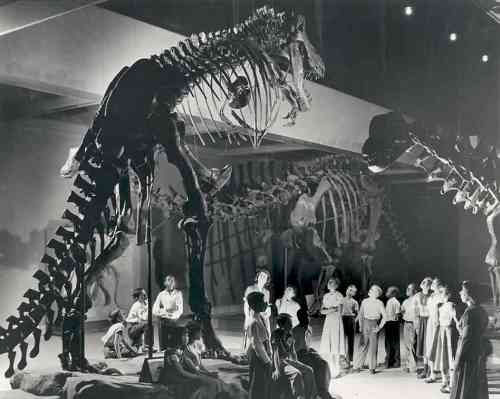

The completed Tyrannosaurus mount, a magnificent sculptural combination of bone, plaster, and steel, was unveiled in 1915 to stunned audiences. With its tooth-laden jaws agape and a long, dragging lizard tail extending its length to over 40 feet, the Tyrannosaurus was akin to a mythical dragon, an impossible monster from a primordial world. This dragon, however, was real, albeit safely dead for 66 million years. The December 3rd New York Times article was thick with hyperbole, declaring the dinosaur “the prize fighter of antiquity”, “the king of all kings in the domain of animal life,” “the absolute warlord of the earth” and “the most formidable fighting animal of which there is any record whatsoever.” Even Osborn got in on the game, calling Tyrannosaurus “the most superb carnivorous mechanism among the terrestrial Vertebrata, in which raptorial destructive power and speed are combined.”

Brian Noble argues that Osborn’s descriptions of T. rex betray his own racial anxiety and fear of obsolescence. As a member of the New York aristocratic class, Osborn supported eugenics and lobbied for race-based quotas on immigration. Within months of penning museum labels that lament the extinction of “great and noble” carnivores like Tyrannosaurus, Osborn was writing that “the greatest danger to the American republic is the gradual dying out…of those hereditary traits through which the principles of our religious, political, and social foundations were laid down and their insidious replacement by traits of a less noble character” (quoted in Noble 2017, pg. 73). Whether knowingly or not, Osborn allowed his fear of the fall of the de facto ruling class to which he belonged influence his interpretation of a long-dead dinosaur.

Hermann’s Tyrannosaurus continued to delight AMNH visitors through the 1980s. Image courtesy of the AMNH Research Library.

Today, we know that the original AMNH Tyrannosaurus mount was inaccurate in many ways. The upright, tail-dragging pose, which had been the most popular attitude for bipedal dinosaurs since Joseph Leidy’s 1868 Hadrosaurus mount, is now known to be incorrect. More complete Tyrannosaurus skeletons have revealed that the tail reconstructed by Osborn and Hermann was much too long. The Allosaurus-inspired feet were too robust, the legs (partially cast from the 1905 holotype) were too large, and the hands had too many fingers. It would be misleading to presume that the prehistoric carnivore’s skeleton sprang from the ground exactly as it was presented, but it is equally incorrect to reject it as a fake. The 1915 mount was a solid representation of the best scientific data available at the time, presented in an evocative and compelling manner.

The AMNH Tyrannosaurus mount was no less than a monument: for paleontology, for its host museum, and for the city of New York. The mount has been a New York attraction for longer than the Empire State Building, and for almost 30 years, AMNH was the only place in the world where visitors could see a T. rex in person. In 1918, Tyrannosaurus would make its first Hollywood appearance in the short film The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. This star turn was followed by roles in 1925’s The Lost World and 1933’s King Kong, firmly establishing the tyrant king’s celebrity status. It is noteworthy that special effects artist Willis O’Brian and model maker Marcel Delgado copied the proportions and posture of the AMNH display exactly when creating the dinosaurs for each of these films. The filmmakers took virtually no artistic liberties, depicting Tyrannosaurus precisely how contemporary scientists had reconstructed it at the museum.

II. A T. rex for Pittsburgh

The Carnegie Museum’s first attempt at restoring the skull of T. rex. Source

In 1941, AMNH ended its Tyrannosaurus monopoly and sold the incomplete type specimen (the partial skeleton described in Osborn’s 1905 publication) to Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History. While it is sometimes reported that this transfer took place to keep the valuable fossils out of harm’s way during World War II (e.g. Larson 2008), the deal was actually underway well before the United States became involved in the war. Carnegie Museum Director Andrew Avinoff spent nearly a year bargaining with Barnum Brown over a price, eventually settling on $100,000 ($1.7 million in today’s dollars) for the fossils with appropriate bases and mounting fixtures. Carnegie staff wasted no time assembling a mount of their own, but since the Tyrannosaurus holotype only included about 18% of the skeleton, most of the Pittsburgh T. rex had to be made from casted and sculpted elements. Somewhat pointlessly, the skull fragments included with the specimen were buried inside a plaster skull replica (above), making them inaccessible to researchers for several decades. Completed in less than a year, the Carnegie Tyrannosaurus was given a more hunched posture than its AMNH predecessor.

The Tyrannosaurus faced off with Diplodocus and Apatosaurus at the Carnegie Museum for more than 60 years. Source

The mid-20th century was a quiet phase for vertebrate paleontology. After enjoying public fame and generous federal support during the late 1800s, paleontology as a discipline was largely marginalized when experiment-driven “hard” sciences rose to prominence. By the 1950s and 60s, the comparably small number of researchers studying ancient life were chiefly concerned with theoretical models for quantifying trends in evolution. Although the aging dinosaur displays at American museums remained popular with the public, these animals were perceived as evolutionary dead-ends, of little interest to the majority of scientists.

While New York and Pittsburgh remained the only places where the tyrant king could be seen in person, the ongoing fame of T. rex was secured in part by two additional museum displays, ironically at institutions that did not have any actual Tyrannosaurus fossils on hand. In 1928, the Field Museum of Natural History commissioned Charles Knight to paint a series of prehistoric landscapes, the most recognizable of which depicts a face-off between Triceratops and a surprisingly spry Tyrannosaurus. In 1947, Rudolph Zallinger painted a considerably more bloated and lethargic T. rex as part of his Age of Reptiles mural at the Peabody Museum of Natural History. Both paintings would be endlessly imitated for decades, and would go on to define the prehistoric predator in the public imagination.

III. Rex Renaissance

RTMP 81.6.1, aka Black Beauty, mounted in relief at the Royal Tyrell Museum. Source

The sparse scientific enthusiasm for dinosaurs that defined mid-century paleontology changed rather suddenly in the 1970s and 80s. The “dinosaur renaissance” brought renewed energy to the discipline in the wake of evidence that dinosaurs had been energetic and socially sophisticated animals. The next generation of paleontologists endeavored to look at fossils in new ways to understand dinosaur behavior, biomechanics, ontogeny, and ecology. Tyrannosaurus was central to the new wave of research, and has been the subject of hundreds of scientific papers since 1980. More interest brought more fossil hunters into the American west, leading to an unprecedented expansion in known Tyrannosaurus fossils.

The most celebrated Tyrannosaurus find from the dinosaur renaissance era came from Alberta, making it the northernmost and westernmost T. rex to date. The 30% complete “Black Beauty” specimen, so named for the black luster of the fossilized bones, was found in 1980 by a group of high schoolers and was excavated by paleontologist Phil Curie. The original Black Beauty fossils were taken on a tour of Asia before finding a permanent home at the newly established Royal Tyrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta. In lieu of a standing mount, Black Beauty was embedded in a faux sandstone facade, mirroring the environment in which the fossils were found and the animal’s presumed death pose. This relief mount set Black Beauty apart from its AMNH and Carnegie predecessors, and even today it remains one of the most visually striking Tyrannosaurus displays.

The mid-sized reconstruction (right) in this 2011 growth series at LACM incorporates Garbani’s juvenile T. rex fossils. Photo by the author.

Tyrannosaurus was once considered vanishingly rare, but by the early 1990s the number of known specimens had increased dramatically. Harley Garbani found three specimens, including the first T. rex juvenile, while prospecting in Montana for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM). “I was pretty excited,” Garbani recounted, “I didn’t figure another of those suckers would ever be found” (quoted in Horner and Lessem 1993). Meanwhile, the Royal Tyrell Museum tracked down a partial T. rex in Alberta that Charles Sternberg had marked in 1946 but never excavated.

One of the most complete Tyrannosaurus specimens was discovered by avocational collector Kathy Wankel while prospecting on Montana land owned by the Army Corps of Engineers. The Museum of Rockies (MOR) excavated the Wankel Rex in 1989, and until recently it was held it trust at the Bozeman museum. All of these specimens have allowed paleontologists to conduct extensive research on the growth rate, cellular structure, sexual dimorphism, speed, and energetics of T. rex, turning the species into a veritable model organism among dinosaurs.

IV. The World’s Most Replicated Dinosaur

Cast of Peck’s Rex, accompanied by a Wankel Rex skull, at the Maryland Science Center. Photo by the author.

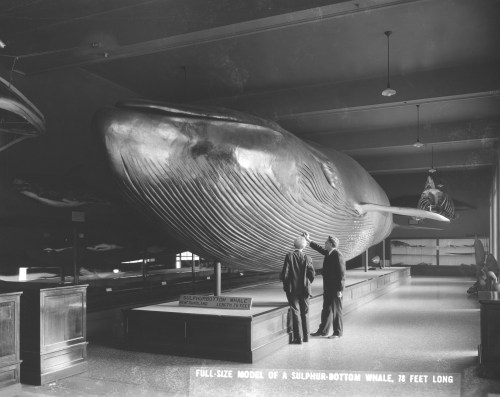

Despite the relative bonanza of new Tyrannosaurus specimens uncovered in the 1980s and 90s, very few of those skeletons were immediately assembled as display mounts. Instead, many museums have purchased complete casts to meet the increasing public demand for dinosaurs. In 1986, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia opened Discovering Dinosaurs, the world’s first major exhibit showcasing active, endothermic dinosaurs. The centerpiece of the exhibit was a cast of the AMNH Tyrannosaurus, posed for the first time in the horizontal posture that we now know was the animal’s habitual stance. The following year, another AMNH cast appeared in the lobby of Denver Museum of Nature and Science in a strikingly bizarre pose, with one leg kicking high in the air. Robert Bakker—the mount’s designer— intended to push boundaries and demonstrate what a dynamic and energetic Tyrannosaurus might be capable of, although the mount has subsequently been described as dancing, kicking a soccer ball, or peeing on a fire hydrant.

Denver’s high-kicking T. rex. Source

Since the late 1990s, however, casts of another specimen have overtaken AMNH 5027 for the title of most ubiquitous T. rex. BHI 3033, more commonly known as Stan, was excavated in South Dakota in 1992 by the Black Hills Institute (BHI), a commercial outfit specializing in excavating, preparing, and mounting fossils. BHI has sold dozens of Stan casts to museums and other venues around the world. At a relatively affordable $100,000 plus shipping, even small local museums and the occasional wealthy individual can now own a Tyrannosaurus mount. With over 50 casts sold as of 2017, Stan is, by a wide margin, the most duplicated and most exhibited dinosaur in the world.

Stan cast at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Photo by the author.

All these new Tyrannosaurus mounts are forcing museums to get creative, whether they are displaying casts or original fossils. Predator-prey pairings are a popular display choice: for example, the Wankel Rex cast at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science is positioned alongside the sauropod Alamosaurus, and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History matches the tyrant dinosaur with its eternal enemy, Triceratops. Meanwhile, the growing number juvenile Tyrannosaurus specimens has allowed for family group displays. LACM features an adult, subadult, and baby, while the Burpee Museum of Natural History pairs its original juvenile T. rex “Jane” with an AMNH 5027 cast. The most unique Tyrannosaurus mount so far is certainly the copulating pair at the Jurassic Museum of Asturias.

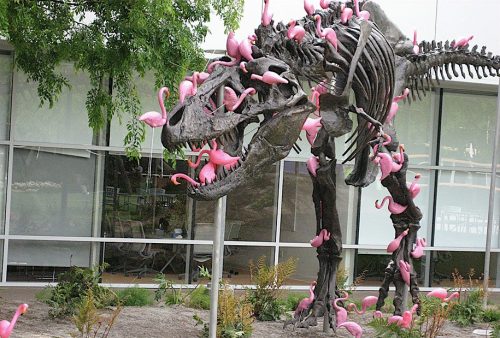

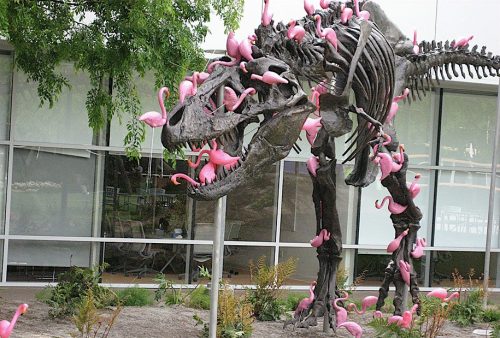

While not as widespread as Stan, casts of the Wankel Rex (distributed by Research Casting International) are increasingly common. This copy at the Google headquarters is periodically attacked by smaller, pinker theropods. Source

Each of these displays gives a substantially different impression of Tyrannosaurus. Depending on the mount, visitors might see T. rex as a powerful brute, a fast and agile hunter, or a nurturing parent (or a gentle lover). Most mounts are accurate insofar that a real Tyrannosaurus probably adopted a similar stance at some point, but the museum’s choice of pose nevertheless influences visitors’ understanding of and attitude toward the dinosaur.

V. Restoring the Classics

An update for the first T. rex ever displayed. Photo by the author.

With dozens of new Tyrannosaurus mounts springing up across the country and around the world, the original AMNH and Carnegie displays began to look increasingly obsolete. However, modernizing historic fossil mounts is an extremely complex and expensive process. The early 20th century technicians that built these displays generally intended for them to be permanent: bolts were drilled directly into the bones and gaps were sealed with plaster that can only be removed by manually chipping it away. What’s more, the cumulative effects of corroding armatures, fluctuating humidity, and vibration from passing crowds had damaged the historic mounts over the course of their decades on display.

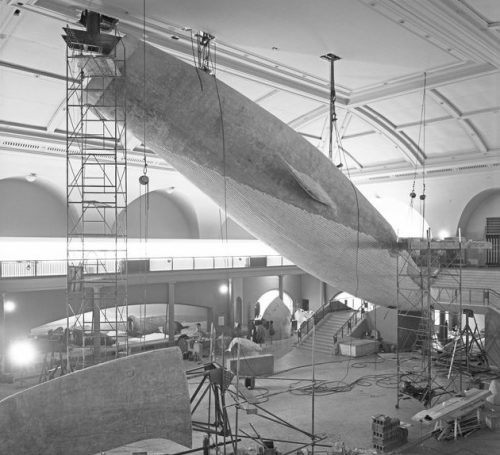

Despite these challenges, AMNH and the Carnegie Museum have both been able to restore and update their classic Tyrannosaurus displays. Between 1987 and 1995, Lowell Dingus coordinated a comprehensive renovation of the AMNH fossil exhibits. As part of the project, chief preparator Jeanne Kelly led the restoration and remounting of the iconic T. rex. The fossils proved especially fragile, and some elements had never been completely freed from the sandstone matrix. It took six people working for two months just to strip away the layers of paint and shellac applied by the original preparators.

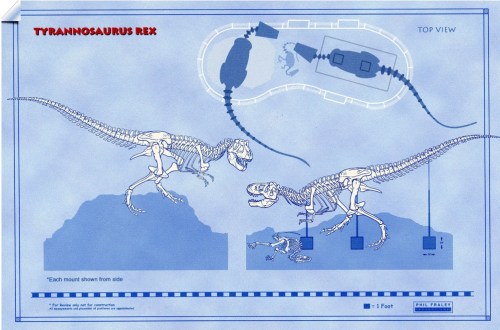

Exhibit specialist Phil Fraley constructed the new armature, which gave the tyrant king a more accurate horizontal posture. While the old mount was supported by obtrusive rods extending from the floor, the new version is actually suspended from the ceiling with a pair of barely-visible steel cables. Each bone is secured to an individual metal bracket, allowing researchers to remove elements for study as necessary. A new cast of the skull was also prepared, this time with open fenestrae for a more natural appearance. Curators Gene Gaffney and Mark Norrell settled on a fairly conservative stalking pose—a closed mouth and subtly raised left foot convey a quiet dignity befitting this historic specimen.

One of many conceptual drawings created by Phil Fraley Productions during the process of planning the Carnegie Museum renovation. Source

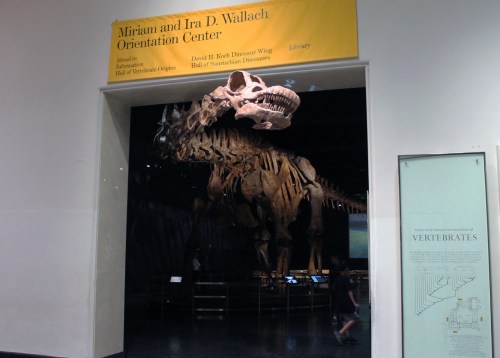

Historically, the Carnegie Tyrannosaurus had never quite lived up to its AMNH predecessor. Although it incorporated the Tyrannosaurus holotype, it was mostly composed of casts from the New York skeleton, and it sported an unfortunately crude replica skull. It is therefore ironic that the Carnegie Museum now exhibits the more spectacular T. rex display, one which realizes Osborn’s plan to construct an epic confrontation between two giant predators.

While less complete than many subsequent finds, the Tyrannosaurus rex holotype is still important because it defines the species. It had not been studied properly since the early 20th century, however, and the skull elements were completely inaccessible—entombed in plaster since 1941. The conservation team overseen by Hans-Dieter Sues sought not only to rebuilt the exhibit mount, but to re-describe the specimen and provide casts of individual bones to other museums. The Carnegie website once hosted a fascinating day-by-day account this process. The page seems to have been removed but an archived version can be found here.

Old meets new: the restored Tyrannosaurus holotype faces off with a cast of Peck’s Rex. Photo by the author.

Phil Fraley, now heading an independent company based in New Jersey, oversaw the construction of the new mount. Michael Holland contributed a new restored skull, actually a composite of several Tyrannosaurus skulls. The mount was completed in 2007, and is displayed alongside a cast of “Peck’s Rex,” a specimen housed at MOR. Despite the difficulty of modernizing the historic specimen, the team reportedly developed a healthy respect for turn-of-the-century mount-makers like Adam Hermann and Arthur Coggeshall, who developed the techniques for making enduring displays of fragile fossils that are still being refined today.

VI. From South Dakota to Chicago

The skull of SUE the T. rex. Photo by the author.

Tyrannosaurus rex displays changed for good in the 1990s thanks to two individuals, one real and one fictional. The latter was of course the T. rex from the film Jurassic Park, brought to life with a full-sized hydraulic puppet, game-changing computer animation, and the inspired use of a baby elephant’s screeching cry for the dinosaur’s roar. The film made T. rex real—a breathing, snorting, drooling animal unlike anything audiences had ever seen. Jurassic Park was a tough act to follow, and in one way or another, every subsequent museum display of the tyrant king has had to contend with the shadow cast by the film’s iconic star.

The other dinosaur of the decade was SUE, who scarcely requires an introduction. SUE is the most complete Tyrannosaurus ever found, with 90% of the skeleton intact. Approximately 30 years old at the time of their death, SUE is also the eldest T. rex known, and within the margin of error for the title of largest. The specimen’s completeness and exquisite preservation has allowed paleontologists to ascertain an unprecedented amount of information about this individual dinosaur. In particular, SUE’s skeleton is riddled with fractured and arthritic bones, as well as evidence of gout and parasitic infections that together paint a dramatic picture of a violent life at the top of the food chain.

It was the events of SUE’s second life, however, that made this the fossil the world knows by name. SUE was discovered in 1990 by Sue Hendrickson (for whom the specimen is named) on ranch land within the Cheyenne River reservation of South Dakota. The Black Hills Institute excavated the skeleton and initially intended to display the Tyrannosaurus at a new facility in Hill City. Even at this point, SUE was a flashpoint for controversy among paleontologists: while several researchers signed up to work with BHI on a monograph about SUE, others did not think a for-profit company was an appropriate place for such an important specimen. Things heated up in 1992, when BHI became embroiled in a four-way legal battle with landowner Maurice Williams, the Cheyenne Council, and the United States Department of the Interior. With little legal precedent for ownership disputes over fossils, it took until 1995 for the District Court to award Williams the skeleton (I recommend the relevant chapter in Grande 2017 as the most evenhanded account of how this went down).

Williams announced that he would put SUE on the auction block, and paleontologists initially worried that the priceless specimen would disappear into the hands of a wealthy collector, or end up in a crass display at a Las Vegas casino. Those fears were put to rest in 1997 when the Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH) won SUE with financial backing from McDonald’s and Disney. Including the auctioneer’s commission, the price was an astounding $8.36 million.

Research Casting International prepared two SUE casts: one for a traveling exhibition and this one at Walt Disney World in Orlando. Photo by the author.

FMNH and its corporate backers did not pay seven figures for SUE solely to learn about dinosaur pathology. SUE’s remarkable completeness would be a boon for scientists, but the fossil’s star power was at least as important for the museum. SUE was a blockbuster attraction that would bring visitors in the door, and the dinosaur’s name and likeness could be marketed for additional earned income. As former FMNH president John McCarter explained, “we do dinosaurs…so that we can do fish” (quoted in Fiffer 2000). A Tyrannosaurus would attract visitors and generate funds, which could in turn support less sensational but equally important collections maintenance.

Once SUE arrived at FMNH, the museum did not hold back marketing the dinosaur as a must-see attraction. A pair of SUE’s teeth went on display days after the auction. This expanded organically into the “SUE Uncrated” exhibit, where visitors could watch the plaster-wrapped bones being unpacked and inventoried. The main event, of course, was the mounted skeleton, which needed to be ready by the summer of 2000. This was an alarmingly short timetable, and the FMNH team had to hit the ground running. Although BHI had already put in 4,000 hours of prep work, much of SUE’s skeleton was still buried in rock and plaster. The bones needed to be prepared and stabilized before they could be studied, and they needed to be studied before they could be mounted.

SUE as displayed from 2000 to 2017. Photo by the author.

After reviewing a number of bids, FMNH selected Phil Fraley to prepare SUE’s armature. Fraley had already remounted the AMNH T. rex at that point, and left his post at the New York museum and founded his own company so that he could work on SUE. Just as had been done with the AMNH skeleton, Fraley’s team built an armature with individual brackets securing each bone, allowing them to be removed with relative ease for research and conservation. No bolts were drilled into the bones and no permanent glue was applied, ensuring that the fossils were not damaged for the sake of the exhibit. SUE was placed right at the heart of the museum, in the half-acre, four-story expanse of Stanley Field Hall. Despite these cavernous surroundings, SUE was given a low, crouching posture—the intent was to give visitors a face-to-face encounter with T. rex.

SUE was revealed to the public on May 17, 2000 with the dropping of a curtain. 10,000 visitors came to see SUE on opening day, and that year the museum’s attendance soared from 1.6 to 2.4 million. To this day, headlines about SUE are common, even outside of Chicago, and the Field Museum’s increasingly avant garde @SUEtheTrex twitter account has 60,000 followers and counting. SUE has been the subject of more than 50 technical papers, several books, and hundreds of popular articles. When FMNH brought SUE to Chicago, they weren’t just preserving an important specimen in perpetuity, they were creating an icon.

VII. Tyrannosaurs Invade Europe

Tyrannosaurus is an exclusively North American animal. It follows that real Tyrannosaurus skeletons have historically only been displayed in American and Canadian museums, while the rest of the world has had to content itself with casts of Stan and the Wankel Rex. This situation changed recently, and there are now two original T. rex skeletons on display in European museums.

The first was Tristan, a Tyrannosaurus collected in 2000 by private collectors. Niels Nielsen, a Danish real estate developer, bought the skeleton for an undisclosed sum (he named the dinosaur Tristan after his son). While it is common for art museums to display privately owned objects, scientific institutions usually avoid such arrangements. There are many reasons for this: it may be a museum’s policy to avoid legitimizing the private market for one-of-a-kind specimens, or they may simply want to steer clear of demands by owners regarding exhibition and interpretation. Perhaps most importantly, scientific research on privately owned specimens is not necessarily reproducible, because there is no guarantee the specimen will remain in a publicly-accessible repository.

Despite these drawbacks, Director Johannes Vogel of the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin decided to accept Tristan as a loan. Paleontologist Heinrich Mallison worked with Nielsen and others to design the mount and plan how it would fit into the exhibit hall. The team opted to pose Tristan as though making a rapid left turn around a “tree” (one of the cast iron columns bisecting the room). Unfortunately, the final armature did not effectively capture the intended twisting motion in the torso, hips, and right leg, and the resulting mount is stiffer looking then the initial renders. The public does not seem to have minded, however. Tristan was unveiled in September 2015 and drew half a million visitors in its first six months on display.

Trix the T. rex in a temporary exhibit space at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center. Source

Europe’s second Tyrannosaurus mount debuted in September 2016 at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden. Named Trix after the Netherlands’ Queen Beatrix, this specimen was collected in Montana by a crew from the museum working in collaboration with the Black Hills Institute. The mount constructed by BHI uniquely includes the original skull, rather than a lightweight replica. This was accomplished by posing Trix in a low running pose, with its head skimming less than a foot above the ground.

VIII. Into the Future

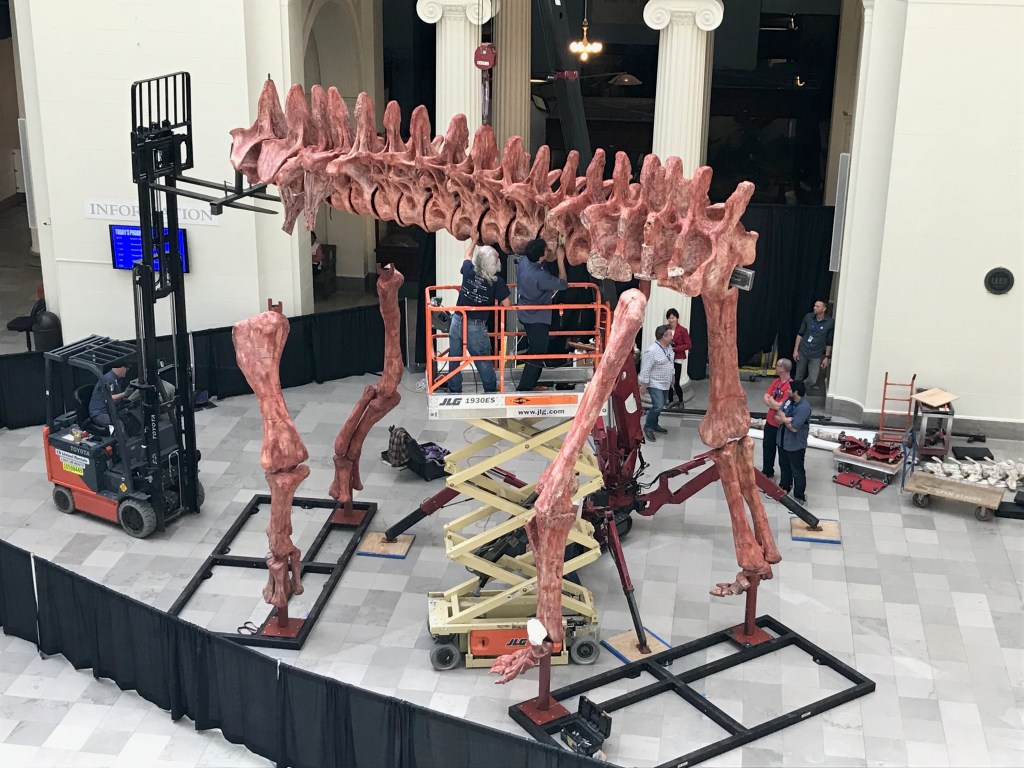

A 1/10th scale 3-D printed model of the Nation’s T. rex recalls the wooden maquettes used at AMNH over a century ago. Source

New T. rex displays just keep coming. In 2019, the National Museum of Natural History reopened its paleontology halls after a five year renovation. The new “Deep Time” exhibition has a brand-new Tyrannosaurus mount as its centerpiece. The specimen in question is the Wankel Rex, which had been held in trust at the Museum of the Rockies since it was excavated in 1989. Found on Army Corps of Engineers land, the fossils are owned by the federal government and therefore an ideal candidate for display at the national museum (technically, they are on a 50 year loan from the Corps to the Smithsonian).

Look closely the fallen Triceratops and you’ll see crushed ribs, a broken horn, and that its head is no longer attached to its body

Although several casts of the Wankel Rex are on display around the world, this is the first time the original fossils have been assembled into a standing mount. For Curator Matt Carrano, it was important that the T. rex was presented like an animal, rather than a sculpture. To accomplish this, he devised a deliriously cool pose, with the Tyrannosaurus poised as though prying the head off a prone Triceratops. Pulling off such a scene was easier said than done. Extreme poses are relatively straightforward when working with lightweight casts, but the degree of dynamism Carrano wanted is much more complicated when creating a frame that safely supports real fossils. Just like Hermann and Christian a century earlier, Matt Fair and his colleagues at Research Casting International started with a 10th scale miniature before moving on to the real skeleton.

Now on display at NMNH, the Wankel Rex has a new nickname: the Nation’s T. rex. This moniker is appropriate: NMNH follows only the Louvre in annual visitation, sometimes topping 8 million people. That means the Nation’s T. rex will soon be the most-viewed Tyrannosaurus skeleton in the world. In all likelihood, 60 million people will pass by the mounted skeleton in the next decade.

SUE the T. rex in their not-quite-finished throne room. Photo by the author.

Nevertheless, the Nation’s T. rex has competition. In 2018, the Field Museum moved SUE to a 6,500 square foot gallery adjacent to the main dinosaur hall. The new exhibition (full disclosure: I was a co-developer on this project) gives SUE some much-needed context. In contrast to the neoclassical space it once occupied, the mounted T. rex is now part of a media-rich experience that Brown, Hermann, and Osborn could have scarcely imagined. An animated backdrop illustrates the waterlogged forests where Tyrannosaurus lived, and a narrated light show provides a tour of SUE’s skeleton—highlighting pathologies and other key features.

With guidance from Pete Makovicky, Tom Cullen, and Bill Simpson, Garth Dallman and colleagues at Research Casting International modified the original SUE mount to correct a range of anatomical inaccuracies and reunite the skeleton with its gastralia (rib-like bones embedded in the belly muscles). This is the first time a Tyrannosaurus skeleton has been mounted with a real gastral basket, and it gives the dinosaur a girthier silhouette. Many lines of evidence have converged onto this new look for T. rex. The animal was not the lithe pursuit predator it was portrayed as in the 1990s, but an ambush hunter with the raw weight and muscle to overpower its bus-sized prey.

SUE’s new digs combine immersive media with elegant and austere design language. Photo by the author.

As we have seen, the number of Tyrannosaurus skeletons on exhibit, whether original fossils or casts, has exploded in recent years. Fifty years ago, New York and Pittsburgh were the only places where the world’s most famous dinosaur could be seen in person. Today, there may well be over a hundred Tyrannosaurus mounts worldwide (most of which are identical casts of a handful of specimens). These displays have evolved over time: new scientific discoveries changed the animal’s pose and shape, new technology has allowed for more enriching and immersive exhibits, and popular media presentations of T. rex have continuously increased the public’s expectations for their encounter with the real thing.

Meanwhile, each T. rex on display exists in a socio-political context: human actors “create the initial and enduring performative iterations of T. rex” (Noble 2016, 71). A century ago, the first-ever T. rex exhibit was encoded with one man’s prejudice and social hangups. In the present, another T. rex—SUE—has become a nonbinary icon. The Field Museum now refers to SUE as “they” instead of “she,” both in the spirit of scientific accuracy (we don’t know SUE’s sex) and LGBTQ+ inclusivity. As explained in a press release, “this kind of representation can make a big difference in the lives of the LGBTQ community. It’s not about politics; it’s about respect. If our Twitter dinosaur gets more people used to using singular “they/them” pronouns and helps some folks out there feel less alone, that seems worth it to us.”

For museums, acquiring and displaying a T. rex is not exactly a risk. As Carrano explained with respect to the Nation’s T. rex, “the T. rex is not surprising, but that’s not its job. Its job is to be awesome.” Specimens like the Nation’s T. rex or SUE are ideal for museums because they are at once scientifically informative and irresistibly captivating. Museums do not need to choose between education and entertainment because a Tyrannosaurus skeleton effectively does both. And even as ever more lifelike dinosaurs grace film screens, museums are still the symbolic home of T. rex. The iconic image associated with Tyrannosaurus is that of a mounted skeleton in a grand museum hall, just as it was when the dinosaur was introduced to the world nearly a century ago. The tyrant king is an ambassador to science that unfailingly excites audiences about the natural world, and museums are lucky to have it.

References

Asma, S.T. 2001. Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Boas, F. 1907. Some Principles of Museum Administration. Science 25:650:931-933.

Black, R. 2013. My Beloved Brontosaurus: On the Road with Old Bones, New Science and our Favorite Dinosaurs. New York, NY: Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Clemens, W.A. and Hartman, J.H. 2014. “From Tyrannosaurus rex to asteroid impact: Early studies (1901-1980 of the Hell Creek Formation in its type area.” Through the End of the Cretaceous in the Type Locality of the Hell Creek Formation in Montana and Adjacent Areas. Eds. Wilson, G.P., Clemens, W.A., Horner, J.R., and Hartman, J.H. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America.

Colbert, E.H., Gillette, D.D. and Molnar, R.N. “North American Dinosaur Hunters.” The Complete Dinosaur, Second Edition. Brett-Surman, M.K., Holtz, T.R. and Farlow, J.O., eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Counts, C.M. 2009. Spectacular Design in Museum Exhibitions. Curator 52: 3: 273-289.

Dingus, L. 1996. Next of Kin: Great Fossils at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Dingus, L. 2004. Hell Creek, Montana: America’s Key to the Prehistoric Past. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Dingus, L. 1996. Next of Kin: Great Fossils at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Fiffer, S. 2000. Tyrannosaurus Sue: The Extraordinary Saga of the Largest, Most Fought Over T. rex ever Found. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Fox, A. and Carrano, M. 2018. Q&A: Smithsonian Dinosaur Expert Helps T. rex Strike a New Pose. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-of-natural-history/2018/07/17/q-smithsonian-dinosaur-expert-helps-t-rex-strike-new-pose

Freedom du Lac, J. 2014. The T. rex that got away: Smithsonian’s quest for Sue ends with different dinosaur. Washington Post.

Glut, D. 2008. “Tyrannosaurus rex: A century of celebrity.” Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King. Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth, eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Grande, L. 2017. Curators: Behind the Scenes of Natural History Museums. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hermann, A. 1909. “Modern Laboratory Methods in Vertebrate Paleontology.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 21:283-331.

Horner, J.R. and Lessem, D. 1993. The Complete T. rex: How Stunning New Discoveries are Changing Our Understanding of the World’s Most Famous Dinosaur. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Johnson, K. and Stucky, R.K. 2013. “Paleontology: Discovering the Ancient History of the American West.” Denver Museum of Nature and Science Annals, No. 4.

Larson, N. 2008. “One Hundred Years of Tyrannosaurus rex: The Skeletons.” Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King. Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth, eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Lee, B.M. 2005. The Business of Dinosaurs: The Chicago Field Museum’s Nonprofit Enterprise. Unpublished thesis, George Washington University.

McGinnis, H.J. 1982. Carnegie’s Dinosaurs: A Comprehensive Guide to Dinosaur Hall at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Institute. Pittsburgh, PA: The Board of Trustees, Carnegie Institute.

“Mining for Mammoths in the Badlands: How Tyrannosaurus Rex Was Dug Out of His 8,000,000 Year old Tomb,” The New York Times, December 3, 1905, page SM1.

Nobel, B. 2016. Articulating Dinosaurs: A Political Anthropology. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Norell, M., Gaffney, E.S. and Dingus, L. 1995. Discovering Dinosaurs: Evolution, Extinction, and the Lessons of Prehistory. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Osborn, H.F. 1906. Tyrannosaurus, Upper Cretaceous Carnivorous Dinosaur: Second Communication. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History vol. 22, pp. 281-296.

Osborn, H.F. 1913. Tyrannosaurus, Restoration and Model of the Skeleton. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History vol 32, pp. 9-12.

Osborn, H.F. 1916. Skeletal Adaptations of Ornitholestes, Struthiomimus, and Tyrannosaurus. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History vol 35, pp. 733-771.

Psihoyos, L. 1994. Hunting Dinosaurs. New York, NY: Random House, Inc.

Rainger, R. 1991. An Agenda for Antiquity: Henry Fairfield Osborn and Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, 1890-1935. Tuscaloosa, Alabama. University of Alabama Press.

Wesihampel, D.B. and White, Nadine M. 2003.The Dinosaur Papers: 1676-1906. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books.