Click here to start the Extinct Monsters series from the beginning.

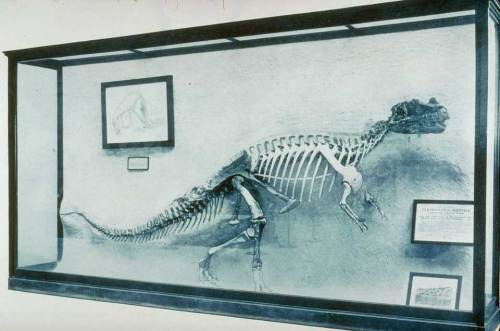

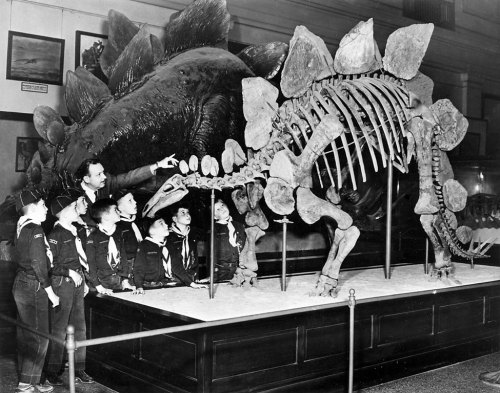

Most of the mounted dinosaur skeletons at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) represent taxa that are well-known to casual paleontology enthusiasts. But nestled amongst household names like Triceratops, Stegosaurus and Diplodocus is an easily-overlooked horned dinosaur that was historically called Brachyceratops montanensis (it’s currently labeled Styracosaurus sp). Tucked away in a glass case behind the giant Triceratops, this pocket-sized ceratopsian may not be the most spectacular display in the exhibit, but it is nevertheless an important one for the Museum. Discovered in 1913 by the Smithsonian’s own Curator of Fossil Reptiles Charles Gilmore, Brachyceratops represents one of only a few dinosaur species excavated, prepared, described and exhibited entirely in-house at NMNH. It is therefore unfortunate that modern researchers have banished the name Brachyceratops to the realm of taxonomic obscurity. What’s more, the days of the Brachyceratops mount, on exhibit since 1922, are numbered: when the NMNH paleontology halls closed for renovation in April 2014, this specimen was be retired to the collections, and is not planned for inclusion when the exhibit reopens in 2019.

During his tenure at NMNH, Gilmore was an inexhaustibly productive writer, publishing at least 170 scientific articles, including numerous important descriptions and reassessments of fossils discovered by O.C. Marsh’s teams in the 19th century. However, Gilmore was much happier studying fossils in his lab than excavating new finds in the field, taking part in a scant 16 NMNH-sponsored field expeditions over the course of his career. A 1913 trip to the Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation in Northeast Montana was therefore unusual for Gilmore. He was following in the footsteps of Eugene Stebinger of the US Geological Survey, who had reported the previous year that the region was only minimally explored but clearly awash in vertebrate fossils.

On this inaugural fossil prospecting trip, Gilmore’s team located abundant remains of fish, small reptiles and dinosaurs, especially hadrosaurs and ankylosaurs. The most notable find, however, was a small bone bed (about six feet square) of ceratopsian fossils, representing at least five individuals. Gilmore described this find in a 1917 monograph, naming the dinosaur Brachyceratops montanensis. Today we know that ceratopsians were quite diverse, particularly during the Campanian, but in the early 20th century the true extent of the group was only just being revealed. Still, it was clear to Gilmore that at an estimated six feet in length, Brachyceratops was an unusually small ceratopsian. He proposed that it may have fed on different plants or occupied a different niche than larger contemporaries like Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus.

In 1917, most of the dinosaur mounts on display at NMNH came from fossils collected by Marsh for the US Geological Survey, and many represented species also on display in New York, Pittsburgh and New Haven. Accordingly, Gilmore was doubtlessly enthused by the prospect of displaying a dinosaur exclusive to Smithsonian. He awarded the task of creating a Brachyceratops mount to preparator Norman Boss, who would spend 345 working days on the project. Of the five individuals found in Montana, USNM 7953 was selected as the basis for the mount because it was the most complete, with the sacrum, pelvis, femora and complete set of caudal vertebrae found articulated in situ. Helpfully, Gilmore published a list of precisely which parts of the mount came from which individual specimen (see below). This was a marked contrast from some of his contemporaries at other museums, who would not bother to record such information, or even actively obscure how many disparate specimens they were using to build their mounts.

Boss based his restoration of Brachyceratops closely on the complete, articulated Monoclonius (=Centrosaurus) specimen (AMNH 5351) discovered by Barnum Brown in 1914. In particular, Boss replicated the angle of the scapulae and the number of vertebrae (22) on the American Museum of Natural History skeleton. Missing bones and portions thereof were sculpted in plaster, easily recognized by their solid color and smooth texture. Just as Gilmore and Boss had done with their 1905 Triceratops mount, the Brachyceratops was given strongly flexed elbows. According to Gilmore, a very large olecranon process on the ulna would have forced all ceratopsians into this somewhat awkward stance. Of particular note is the restoration of the skull, which was found shattered into dozens of pieces, many smaller than one inch. A close look at the specimen reveals how Boss painstakingly reassembled these fragments. Unfortunately, this is difficult in the exhibit hall because the mount is posed with the side of the skull that is mostly plaster facing visitors.

Norman Boss puts the finishing touches on the Brachyceratops mount. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Archives.

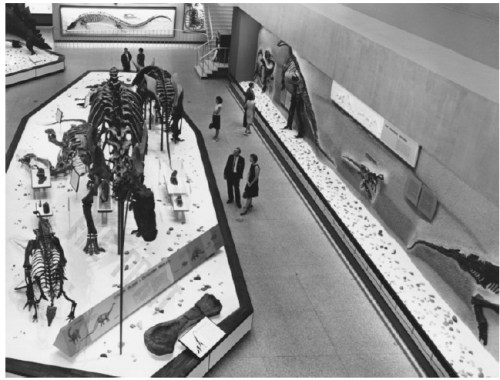

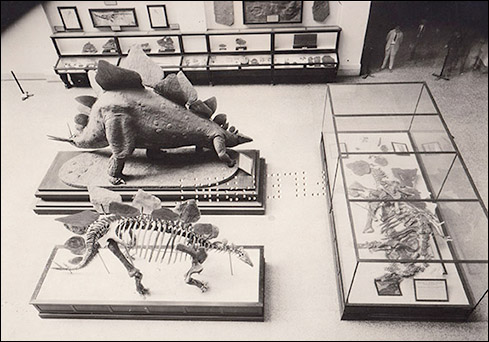

The completed Brachyceratops mount was placed on exhibit in 1922, on the same pedestal in the Hall of Extinct Monsters as the Triceratops. The substrate beneath the mount was colored and textured to match the Two Medicine Formation sandstone in which the fossils were found. Gilmore also prepared one of his charming models of Brachyceratops, mirroring the pose of the mount, but it is unclear whether it was ever exhibited.

The Brachyceratops has remained on view through each subsequent renovation of the fossil halls, always placed close to Triceratops. This close association has prompted many visitors to mistake the diminutive Brachyceratops for a baby Triceratops, and in fact these visitors are on the right track. While Gilmore always described Brachyceratops as an unusually small but full-grown ceratopsian, Scott Sampson and colleagues confirmed in 1997 that all five specimens were juveniles. A century’s worth of new fossil discoveries has provided modern paleontologists with a thorough understanding of ceratopsian ontogeny, and characteristics like the unfused nasal horn clearly mark the mounted Brachyceratops as a young animal. Unfortunately, Gilmore’s Brachyceratops specimens lack any good diagnostic features that could link it to an adult form. According to Andrew McDonald, the most likely candidate is Rubeosaurus ovatus, which was, incidentally, discovered by Gilmore on a 1922 repeat trip to the Two Medicine site. Nevertheless, without the ability to recognize other growth stages of the same species, the name Brachyceratops is unusable and is generally regarded as a nomen dubium.

It is not difficult to surmise why the Brachyceratops would end up near the bottom of the list of mounts to include in a renovated gallery. It is not especially large or impressive, it doesn’t have a recognizable name (or any proper name at all, really) and it doesn’t tell a critical story about evolution or deep time. With limited space available and new specimens being prepped for display, little Brachyceratops will have to go. It’s not all bad, though. Taking these fossils off exhibit will make them more accessible to researchers, and allow them to be closely examined in all aspects for the first time in decades. Perhaps one day soon we will have a clearer idea of the identity of one of Gilmore’s great finds.

References

Gilmore, C.W. (1917). Brachyceratops, a Ceratopsian Dinosaur from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana, with Notes on Associated Fossil Reptiles. Washington, DC: US Geological Survey.

Gilmore, C.W. (1922). The Smallest Known Horned Dinosaur, Brachyceratops. Proceedings of the US National Museum 63:2424.

Gilmore, C.W. (1930). On Dinosaurian Reptiles from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana. Proceedings of the US National Museum 77:2839.

McDonald, A.T. (2011). A Subadult Specimen of Rubeosaurus ovatus (Dinosauria: Ceratopsidae), with Observations on other Ceratopsids from the Two Medicine Formation. PLoS ONE 6:8.

Sampson, S.D., Ryan, M.J. and Tanke, D.H. (1997). Craniofacial Ontogeny in Centrosaurine Dinosaurs: Taxonomic and Behavioral Implications. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 12:1:293-337.