In 1801, naturalist and painter Charles Wilson Peale assembled in Philadelphia the skeleton of a mastodon (Mammut americanum).While Peale’s mastodon was not the first fully assembled fossil animal put on display, it was assuredly the first display of this type to capture widespread public attention, particularly in the United States. What’s more, the mastodon became an important symbol for the untold natural wonders of the American continent, which was still largely unexplored (by European colonists) at the beginning of the 19th century. Finally, Peale’s mastodon made clear to the public one of the most important principles of modern biology: the idea that organisms can become extinct.

The Peale Museum mastodon, as illustrated by Charles Peale’s son, Rembrandt.

The Peale Museum mastodon, as illustrated by Charles Peale’s son, Rembrandt.An extinct giant

The story of the mastodon mount actually began a full century before the 1806 debut. In 1705, a farmer in Claverack, New York found an enormous tooth that had eroded out of a hillside. The farmer traded the tooth to a local politician, and it eventually made it its way into the hands of New York’s colonial governor, Edward Hyde, 3rd Earl of Clarendon. Hyde in turn sent the tooth to London, describing it as a remnant of an antediluvian giant. As word of the remains of a giant spread, other Americans soon began reporting similar finds. Throughout the colonies, giant bones, teeth, and tusks began to be uncovered. While early reports called these fossils the remains of “incognitum,” or “the unknown,” naturalists caught on reasonably quickly that these were not the bones of giant men but of elephant-like creatures.

At this point a brief digression on etymology and taxonomy is required. For most of the 19th century, the American fossil elephants were invariably called “mahmot” or “mammoth.” This was an Anglicization of the Old Vogul term maimanto (meaning earth-horn), which referred to giant tusks occasionally found in Siberia. It is unclear, however, who first made the correct connection between the frozen mammoths of Siberia and the American fossil skeletons. Credit for adopting “mammoth” as a synonym for “big” goes to Thomas Jefferson, who was fascinated by paleontology and the mammoth fossils in particular.

It was not until 1817 that French anatomist Georges Cuvier recognized that there were at least two types of extinct American proboscideans: the taller mammoths and stockier mastodons. Unequivocally demonstrating the staggering repression of the Victorian era, Cuvier coined the name “mastodon,” meaning nipple tooth, because apparently he thought the animal’s most distinguishing feature was that its teeth looked like breasts.

The American elephantine fossils raised difficult questions for naturalists. The fossils clearly belonged to animals that had never been seen alive, which meant that the entire species must have died out. This concept of extinction was new to science, and it challenged the biblically-inspired presumption that all species had originated in a single creation event. Cuvier was a leader in the 19th century scientific movement known as catastrophism–the idea that extinctions were the result of periodic disasters, such as floods. While Cuvier himself rejected the idea that populations of organisms could avoid extinction by adapting and changing, his work on extinction would prove important when Charles Darwin worked out the process of evolution several decades later.

Unearthing the mastodon

In 1789, Nicholas Collin of the American Philosophical Society proposed a search for a complete mammoth skeleton, in order to resolve the animal’s identity and the question of its extinction once and for all. Collin’s call was answered by Charles Wilson Peale, founder of America’s first modern museum. Peale is best known today as a portrait artist during the American Revolution, but he was also the founder of the Peale Museum in Philadelphia. Although semi-formal collections of interesting natural specimens had existed before, Peale uniquely fashioned his institution as a space for public education, rather than a private vanity project. On the second floor of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, Peale arranged displays of mammals, birds, and plants in a scala naturae, which was the contemporary understanding of natural order. Peale intended the museum to be a public resource that would improve visitors’ moral character through lessons in science, as was made clear by the slogan printed on every ticket, “the birds and beasts will teach thee.”

In 1799, a farmer named John Masten reported that he had found bones of “an animal of uncommon magnitude” on his land outside Newburgh, New York. Masten gathered a large party of friends and neighbors to help excavate the find. This proved to be a little too much fun: the crowd eventually descended into alcohol-fueled chaos, and many of the fossils were destroyed. Nevertheless, Peale decided to pay Masten a visit, with the hope of securing mammoth fossils for his museum. Peale ended up paying Masten $200 for the surviving fossils, plus another $100 for the right to search his land for more remains. Peale returned to Masten’s farm with a better-organized crew and $500 in additional funding from the American Philosophical Society. The ensuing excavation is the subject of Peale’s 1806 painting, The Exhumation of the Mastodon, shown below.

Although highly dramatized, The Exhumation of the Mastodon provides the best available record of the event. Since the pit where Masten first found the bones had filled with water, Peale oversaw the construction of a huge wooden wheel, which drove a conveyor belt hauling buckets of water out of the work site. Peale himself can be seen on the right, presiding over his small army of excavators. The well-publicized project eventually uncovered most of a mastodon. Exploring a few nearby farms, Peale’s workers eventually accumulated enough material to build a complete skeleton, most notably a mandible found on another farm down the road. In what was either showmanship or genuine confusion regarding the diets of elephants, Peale said of the find, “Gracious God, what a jaw! How many animals must have been crushed beneath it!” (quoted in Simpson 1942, 159).

The mastodon on exhibit

Once the mastodon skeleton had been transported to Philadelphia, the process of building the mount fell upon Peale’s son Rembrandt and Moses Williams, a free man of color who worked for the Peales. It took three months to articulate the skeleton, although sadly the details of how it was mounted on its armature are lost to history. Initiating a practice that would become necessity for most fossil mounts in years to come, Rembrant filled in missing parts of the mastodon skeleton (the top of the cranium and the tail) with sculpted elements. In addition, wooden discs were placed between vertebrae, slightly exaggerating the mount’s total length.

The completed mastodon mount was unveiled in 1802, in the main hall of the American Philosophical Society. Shortly thereafter, it was moved to the Peale Museum at Independence Hall. For 50 cents (plus regular admission), the visiting public could marvel at the creature Peale touted as “the first of American animals” and “the largest of terrestrial beings.” The mastodon (still being called a mammoth at that time) was a sensation, stirring up fascination with natural science, the prehistoric past, and no small amount of ours-is-bigger-than-yours patriotism in the young United States. In 1822, Peale would commemorate the unveiling of the mastodon with his self portrait, The Artist in His Museum. Ever the showman, Peale ensured that the skeleton in his painting is only barely visible below the rising curtain.

“The Artist in His Museum” by Charles Peale, 1822.

“The Artist in His Museum” by Charles Peale, 1822.After Peale’s death in 1827 his museum floundered, and was eventually reduced from a meritorious educational institution into a circus of cheap spectacle. It shut down for good in 1848, and the mastodon (by then one of many similar mounts) was put up for auction. There are several conflicting accounts of what became of the mount, including the suggestion that it was destroyed in a fire, but in fact Peale’s mastodon has survived to the present day. Johann Jakob Kaup purchased the skeleton for the Landesmuseum in Durmstadt, Germany, and it has remained on display there ever since.

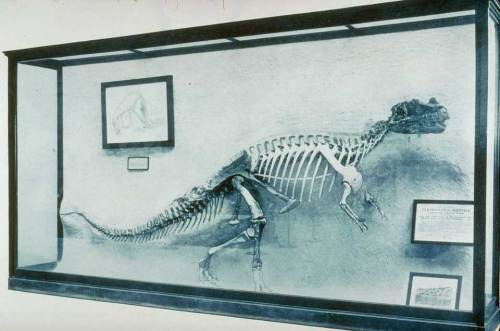

Peale’s mastodon survives in Durmstadt, Germany. Source

Peale’s mastodon survives in Durmstadt, Germany. SourcePeale’s mastodon left an unmistakable legacy for both paleontology and public education. Today, the public conception of prehistory is inseparably connected to the image of towering mounted skeletons in museum halls. But fossils do not come out of the ground bolted to steel armatures, so it is largely thanks to Peale that mounts have become the most enduring means of sharing paleontology with the public.

References

Carpenter, K., Madsen, J.H. and Lewis, L. (1994). Mounting of Fossil Vertebrate Skeletons. Vertebrate Paleontological Techniques, Vol. 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Connriff, R. (2010). Mammoths and Mastodons: All American Monsters. Smithsonian Magazine. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/Mammoths-and-Mastodons-All-American-Monsters.html

Semonin, P. (2000). American Monster: How the Nation’s First Prehistoric Creature Became a Symbol of National Identity. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Simpson, G.G. (1942). The Beginnings of Vertebrate Paleontology in North Ameirca. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 86:130-188.