Click here to start the Extinct Monsters series from the beginning.

The National Museum of Natural History houses the world’s most complete assemblage of fossil marine mammals. The crown jewel of this collection is assuredly the historic mounted Basilosaurus, which was until recently the only mount of its kind composed of original fossils. Since 2008, this ancestral whale has been suspended from the ceiling of the Sant Ocean Hall, but these fossils have actually been on near-continuous display for 120 years and counting. Technically this wasn’t the first time Basilosaurus fossils were used in a mounted skeleton (Albert Koch’s absurd chimera “Hydrarchos the sea serpent” preceded it by 60 years), but it was the first time this species was mounted accurately and under scientific supervision.

Basilosaurus was named by anatomist Richard Harlan in 1834. The name means “king lizard”, since he erroneously thought the bones belonged to a giant sea-going reptile. Richard Owen later re-identified the bones as those of a whale, and coined the new name “Zueglodon” (yoke tooth). While the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature decrees that the first published name must be used, late 19th century paleontologists apparently preferred to use Owen’s junior synonym.

Basilosaurus cast in the original USNM, now called the Arts and Industries Building. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

In 1884 Charles Schuchert, an Assistant Curator at the United States National Museum, went to Clarke County, Alabama in search of “Zueglodon” remains. This would be the very first fossil-hunting expedition ever mounted by the Smithsonian. Decades earlier, Koch came to the same region to collect the fossils he used to assemble Hydrarchos, and local people had been familiar with the whale bones long before that.

Schuchert did not find the complete Basilosaurus skeleton he was looking for, but he did recover a reasonably complete, albeit fragmented, skull and jaw. He returned to Alabama in 1886 and collected an articulated vertebral column, a pelvis, and enough other elements to assemble a composite skeleton. Museum staff used the fossils to produce plaster casts, and combined them with sculpted bones to construct a replica “Zueglodon.” The whale was first unveiled at the Atlanta Exposition in 1895, before finding a home in the original United States National Museum (now the Arts and Industries Building). The 40-foot skeleton hung from the ceiling of the southwest court, with the original fossils laid out in a long case beneath it.

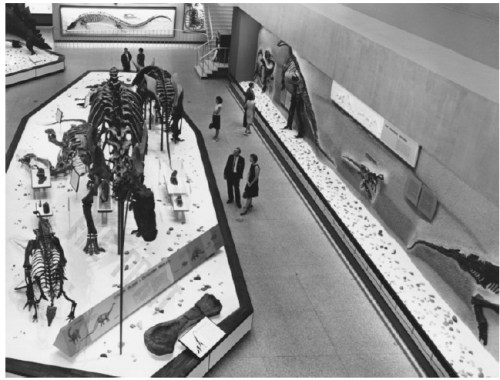

Basilosaurus as the centerpiece of the Hall of Extinct Monsters sometime before 1930. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

In 1910, the USNM relocated to a larger building on the north side of the national mall, which is now of the National Museum of Natural History. The east wing of the new museum became the Hall of Extinct Monsters, and has been the home of fossil displays at the Smithsonian ever since. The Basilosaurus was selected as the centerpiece of the new display, as its great length and toothy appearance made it popular with visitors. In honor of the occasion, preparator James Gidley reworked the old plaster mount to incorporate Schuchert’s original fossils. A series of caudal vertebrae from a third Basilosaurus specimen was also used. Still labeled “Zueglodon”, the mount was completed in 1912, about a year after the Hall of Extinct Monsters first opened to the public. As Curator of Geology George Merrill explained, the wide-open floor plan of the new hall allowed visitors to walk all the way around the mount, and inspect its every aspect up close.

During the 1960s and 70s, Basilosaurus occupied a case in the fossil mammal exhibit in Hall 5. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

In 1931, the Basilosaurus was upstaged by a new centerpiece: the mounted Diplodocus that took Charles Gilmore and his team more than a decade to assemble. The Diplodocus took the front-and-center position (where it remained until 2014), while the Basilosaurus was relocated to the south side of the hall. The Great Depression and World War II ensured that the east wing exhibits remained largely unchanged for nearly three decades after that, but the space was eventually renovated in the early 1960s as part of a Smithsonian-wide modernization campaign. In its new incarnation, the east wing’s open spaces were carved into smaller galleries dedicated to different groups of ancient life. With the central Hall 2 occupied by dinosaurs and fossil reptiles, the Basilosaurus joined the other Cenozoic mammals in Hall 5. This gallery became “Life in the Ancient Seas” in 1989, but the Basilosaurus remained in place.

For the Ancient Seas gallery, Basilosaurus was remounted with an arched tail. Photo by Chip Clark.

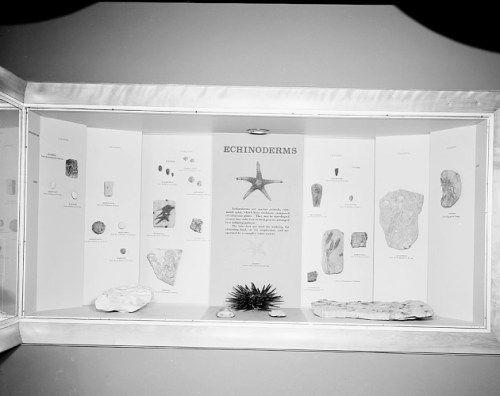

Life in the Ancient Seas was a very different setting for the Basilosaurus than the Hall of Extinct Monsters, reflecting the significant changes in museum interpretation that occurred during the 20th century. The historic exhibit showcased the breadth of the museum’s fossil collection in a fairly neutral environment. Interpretation was minimal, and generally intended for a scholarly audience. In contrast, Life in the Ancient Seas was an immersive educational experience (no pun intended). The Basilosaurus and other marine mammal skeletons were posed over a papier-mâché ocean bottom, while a blue and turquoise color palate and even shimmering lights contributed to the illusion of traveling through an underwater world. Combined with text panels written with a jovial, inviting tone, the net effect was an exhibit pitched to a general audience at home with multimedia.

The Basilosaurus was moved once more in 2008, when it was incorporated in the enormous new Ocean Hall. In its 5th position in a little over a century, the skeleton now hangs from the ceiling as part of an exhibit on whale evolution. Moving the historic skeleton was not an easy task, and took about six months of work. NMNH staff collaborated with Research Casting International to disassemble the skeleton, stabilize and conserve each bone, and finally remount the Basilosaurus on a new armature. In the new mount, each bone rests in a custom cradle with felt padding, to prevent vibration damage caused by the crowds passing beneath it. Smithsonian paleontologists also reunited the whale with its hind legs, which Schuchert found alongside the articulated vertebral column in Alabama but were, until recently, thought to belong to a bird.

This latest setting for Basilosaurus is a happy medium between museums past and present. The historic gallery occupied by the Ocean Hall has been restored to its original neoclassical glory, and much like the original Hall of Extinct Monsters visitors have clear sight lines across the space. Rather than being led on rails through a scripted exhibit experience, visitors can move freely through the gallery, bouncing among the objects they find compelling. At the same time, however, the Basilosaurus is explicitly contextualized as an example of the transformative power of evolution. Presented alongside cast skeletons of Maiacetus and Dorudon, this display makes whales’ evolutionary link to terrestrial mammals crystal clear.

This post was last updated on 1/8/2018.

References

Gilmore, C.W. (1941). A History of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology in the United States National Museum. Proceedings of the United States National Museum No. 90.

Marsh, D.E. (2014). From Extinct Monsters to Deep Time: An ethnography of fossil exhibits production at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. http://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/50177

Meet Basilosaurus, an Ancient Whale (2008). Smithsonian Institution. http://www.mnh.si.edu/exhibits/ocean_hall/meet_basilosaurus.html