The blog has been quiet this year, and a major reason for that is that my day job has been anything but. So in lieu of discussion about exhibits from decades past, here’s a bit about the decision making that went into some brand new ones that I worked on this year! New, in-depth articles about traditional Extinct Monsters fare are in progress, I promise.

Reptiles Alive

As the title suggests, Reptiles Alive is an exhibition that features live reptiles. This was a collaborative project between the Field Museum and Clyde Peeling’s Reptiland, a zoo in Allenwood, Pennsylvania. Reptiland provided the animals, their enclosures, and their human caretakers, while we designed and built a full-sized exhibition around them. I wrote and developed the new material alongside Associate Curator of Herpetology Sara Ruane.

Reptiles Alive is straightforwardly about getting people excited to see and learn about incredible animals. Often, an exhibition calls for a grand narrative or lofty learning goals, but I thought the best approach for this one was to simply follow the “rule of cool.” Does a fact or image or display idea make people say, “wow, that’s amazing?” Then it it belongs in the show. Sometimes “because it rules” is a perfectly valid reason to do something—that’s why we have a 110-foot black mamba skeleton hanging from the ceiling.

Reptiles Alive is organized Planet Earth-style. Each section features a biome type, but isn’t constrained to a particular part of the world. This allowed us to have some fun with the design and create unique soundtracks and lighting for each area: baking sunlight radiates over the desert section while animated snakes slither across the floor in the tropics.

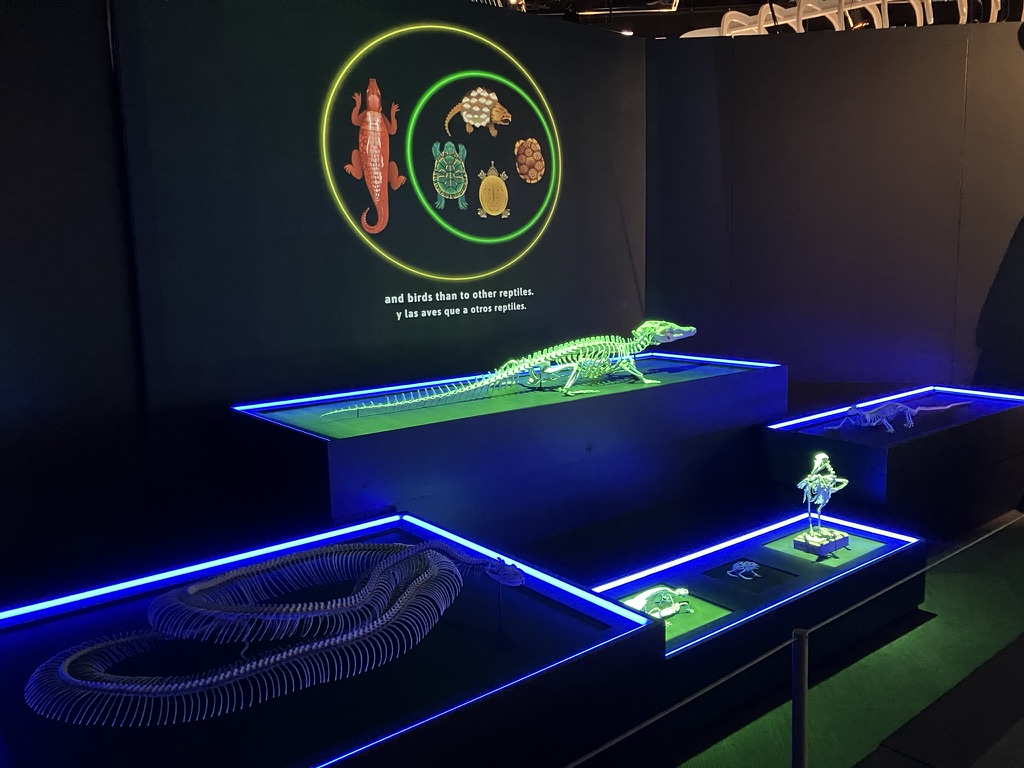

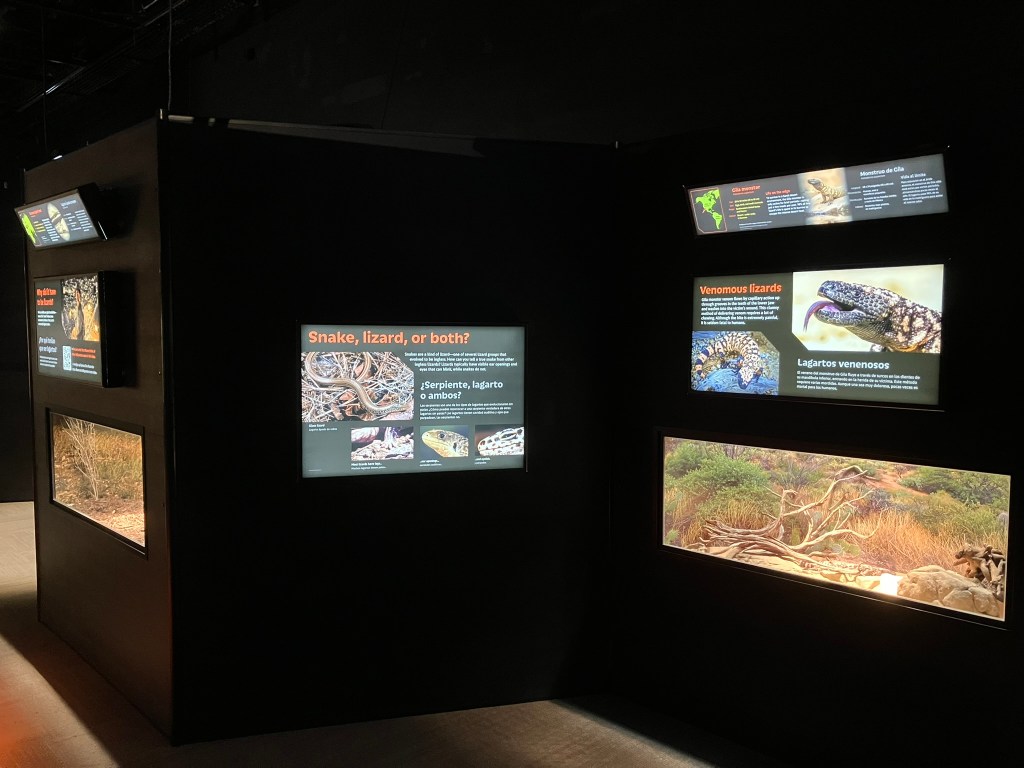

The other benefit of the biome-based organization is that we didn’t have to get bogged down with phylogeny in every label. Reptile classification is full of nested categories and apparent contradictions: for example, a snake is a kind of lizard, but there are are also legless lizards that aren’t snakes. Rather than distracting visitors with constant definitions and explanations, we opted to move the entire classification discussion to a single, prominent “object theater” near the exhibition’s entrance. Spotlights shine on mounted skeletons in different combinations as a narrator walks visitors through the main reptile groups and how to recognize them, while also clarifying that amphibians are not reptiles (but birds are). In under two minutes, visitors gain a shared vocabulary they can use as they explore the rest of the exhibition.

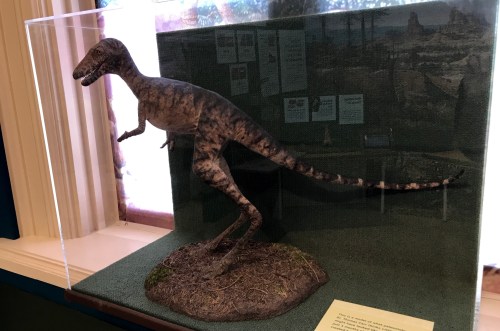

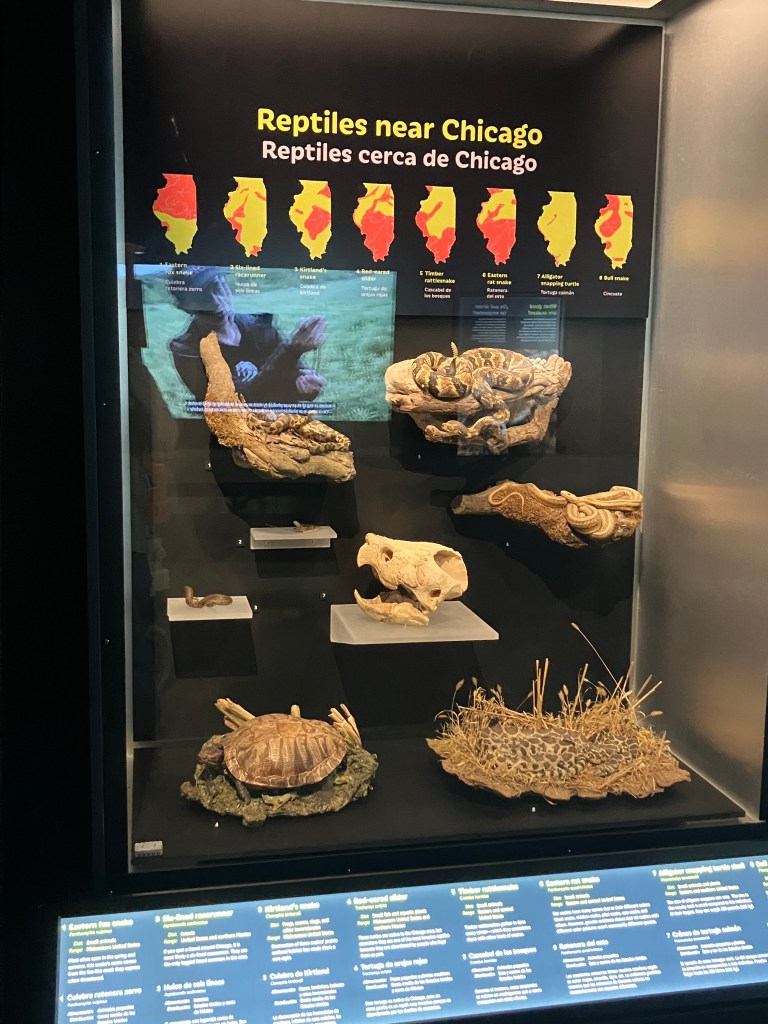

Naturally, the live animals are the stars of the show. Gwangi, a 38-year-old, puppy-tame Cuban rock iguana, is my favorite, but it’s also a lot of fun watching the European glass lizard dig in and out of his bedding, or seeing the reticulated python splash around in the water. We also made use of the museum’s collection of spectacularly life-like model reptiles from the early 20th century, and commissioned a few new ones as well. The models introduce visitors to creatures they might never have heard of, as well as one with a role in Field Museum lore.

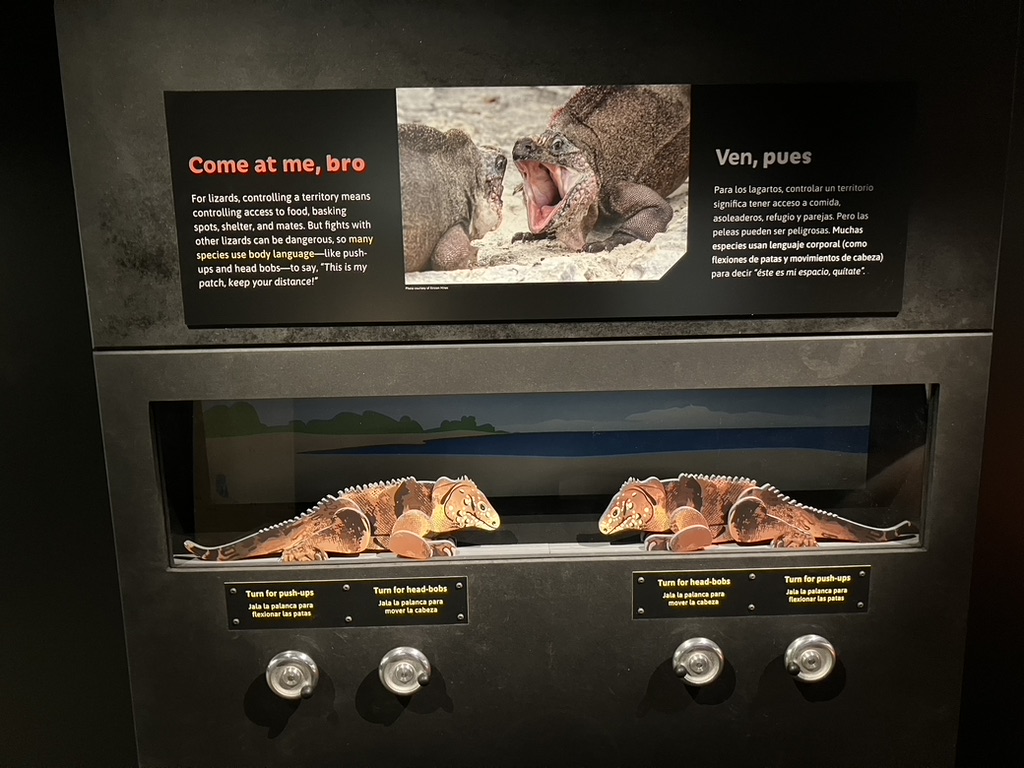

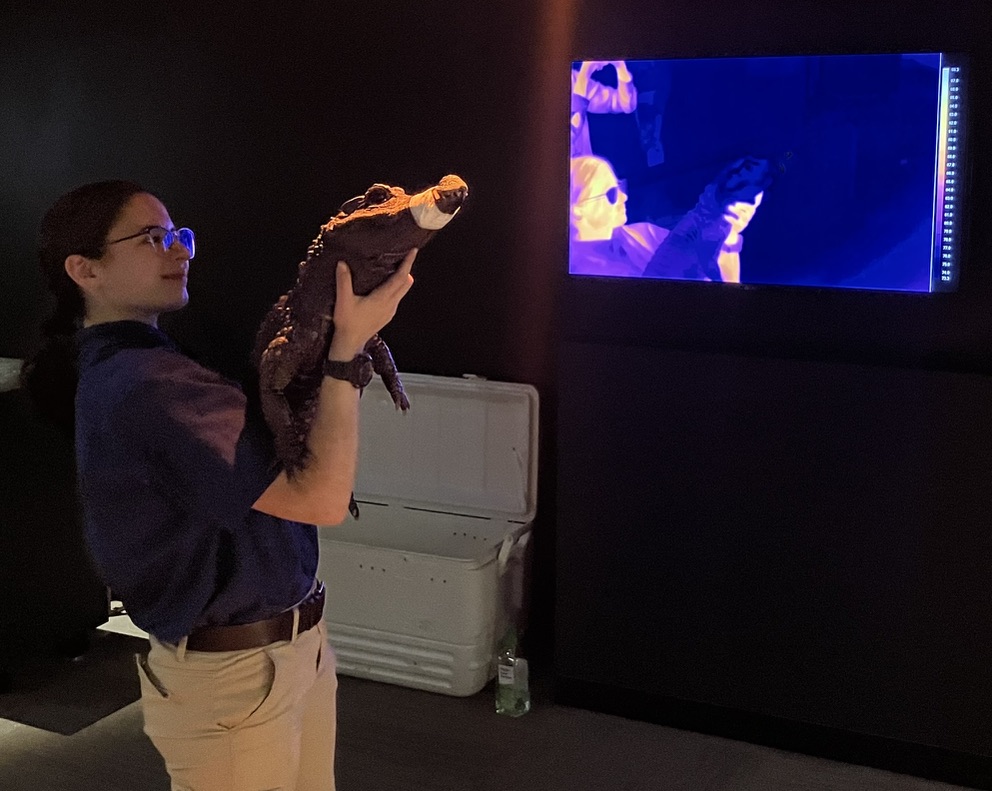

There are no touchscreens in Reptiles Alive. Instead, we went all-in on simple, tactile interactives. Whether you’re puppeteering a pair of iguanas to demonstrate lizard body language or testing your puny human strength against the bite force of a Nile crocodile, the action being performed always directly illustrates the concept under discussion. The fanciest piece of hardware in the exhibition is a thermal camera. It’s one thing to tell visitors that reptiles are cold-blooded, but it’s quite another to see the zookeeper hold a room-temperature snake up to the camera. The human glows orange while the snake matches the blues and purples of the space around it.

The final display originated as a joke. We wanted to make a big diorama, but detailed botanical models are just about the most expensive and time-consuming thing you can make. Thinking about reptile habitats without much vegetation, I glibly offered that we could recreate the “gator on a golf course” scene from Happy Gilmore. But we soon realized that was the perfect ending for our exhibition: draining swampland to build golf courses is an example of how humans are invading reptile habitats. That means we’re going to encounter reptiles more often, and we’ll need to learn to live alongside them. Hopefully, visitors that came in fearing reptiles will leave with respect and admiration for them.

Reptiles Alive runs until April 2026.

Changing Face of Science: Sara Ruane

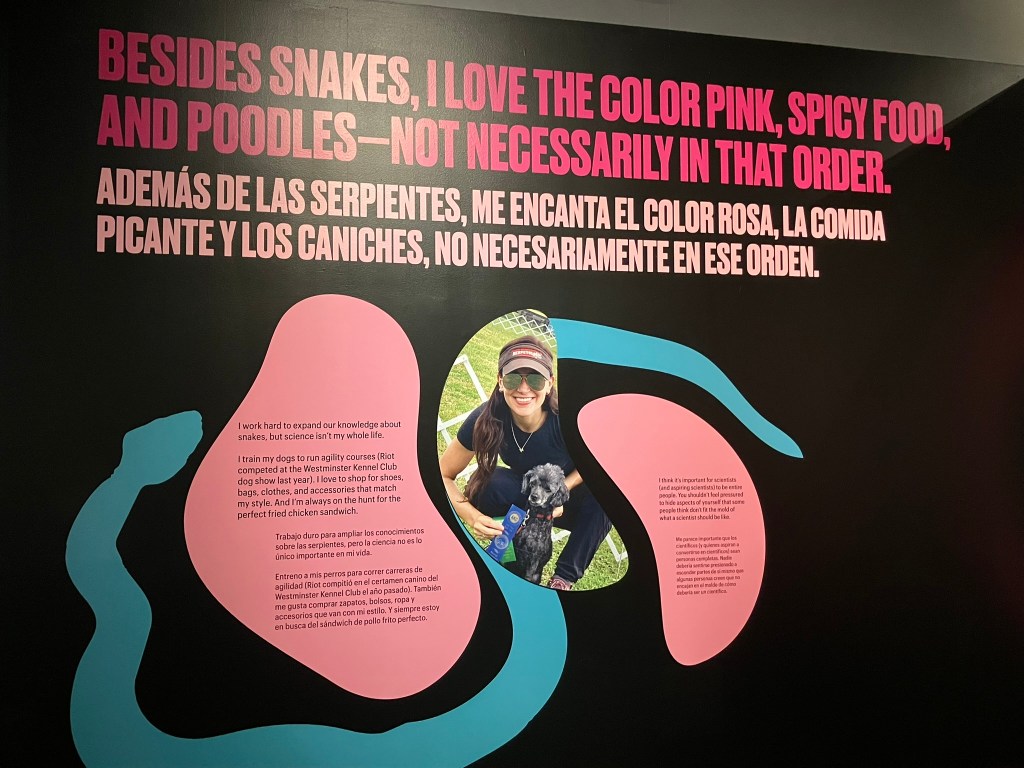

In 2022, the Field Museum launched The Changing Face of Science, a series of exhibitions that profile scientists affiliated with the museum who are women or people of color. The series is intended to inspire young visitors and show how how diverse perspectives and backgrounds can contribute to science.

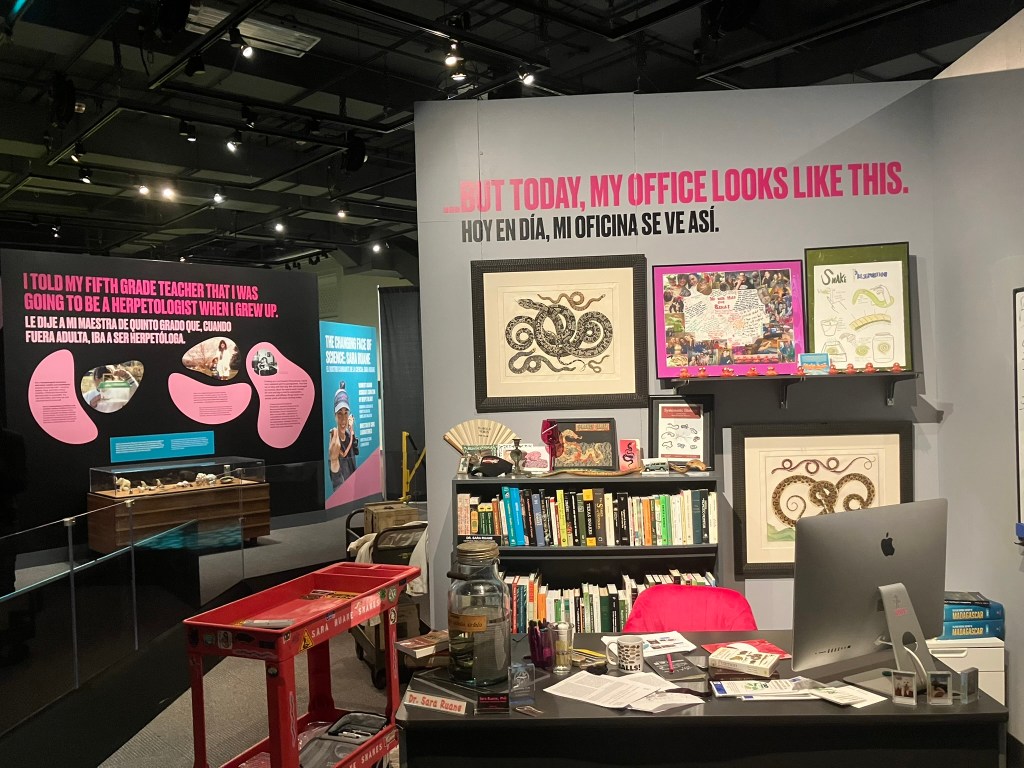

The latest entry in the series features aforementioned herpetology curator Sara Ruane. Sara studies the diversity and evolution of snakes, and has been fascinated by reptiles from a young age. However, Sara also wanted the exhibition to communicate that being a scientist is only part of who she is. Sara loves training her toy poodles, shopping for designer bags, and curating her unique fashion sense—you can be a great scientist while also being a complete person.

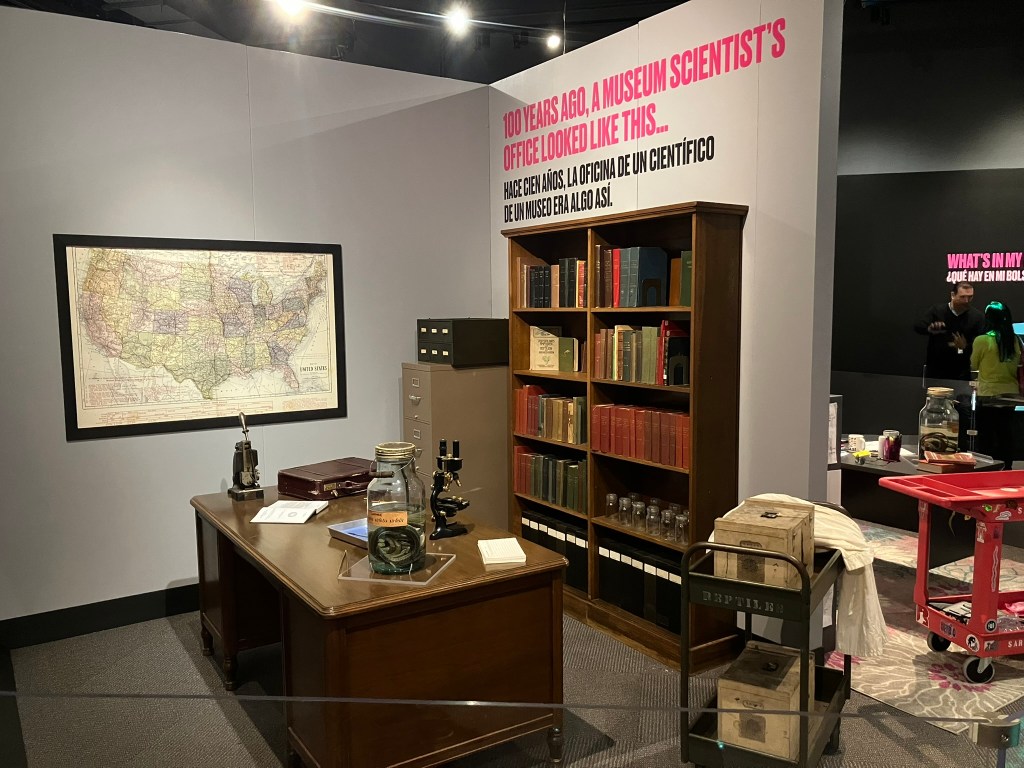

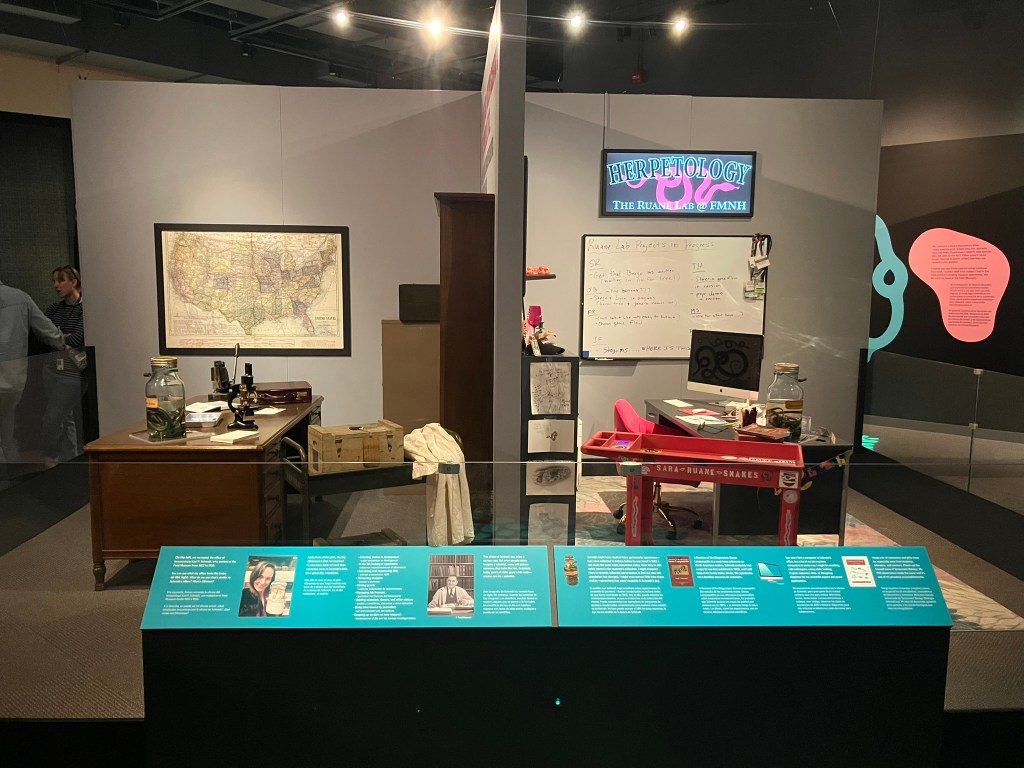

Displays include a recreation of a tabletop “museum” (that Sara made for her family at age six) and the contents of her fieldwork bag (which include everything from a Leatherman multitool to lipgloss). The centerpiece is a pair of office dioramas. One is Sara’s office today, and the other is that of Karl Schmidt, who was the Field Museum herpetology curator a century ago. I think it’s fair to say that we had a blast reconstructing Schmidt’s office, using his original desk and much of his actual book collection. Visitors are encouraged to compare the two spaces: Schmidt’s office is more traditionally professorial, while Ruane’s is full of fun decorations and mementos. But both scientists have the same jar of garter snakes on their desks (museum specimens are an eternal resource), and are referencing the same book (books are also eternal).

Sara’s exhibition runs until January 2026.

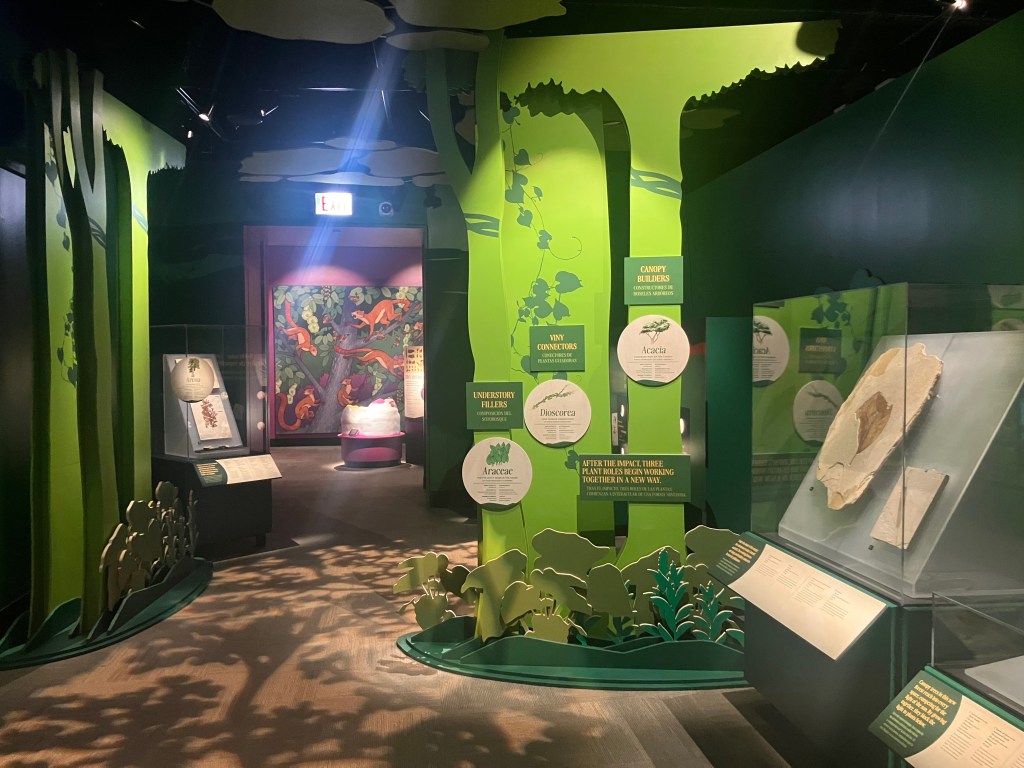

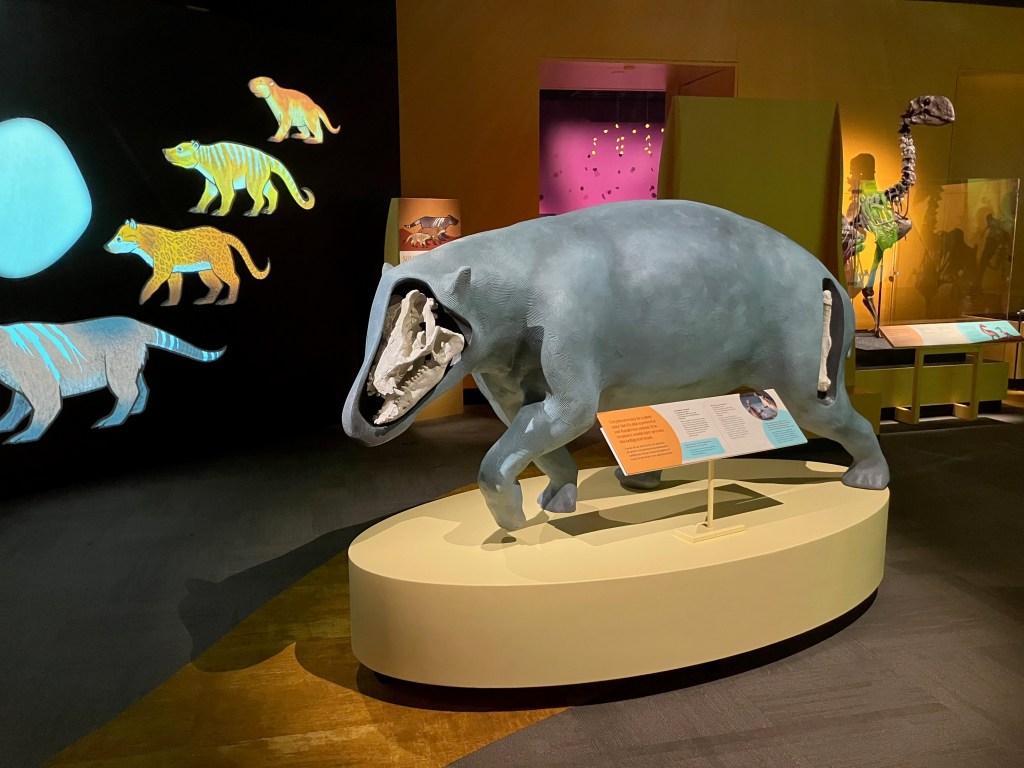

After the Age of Dinosaurs

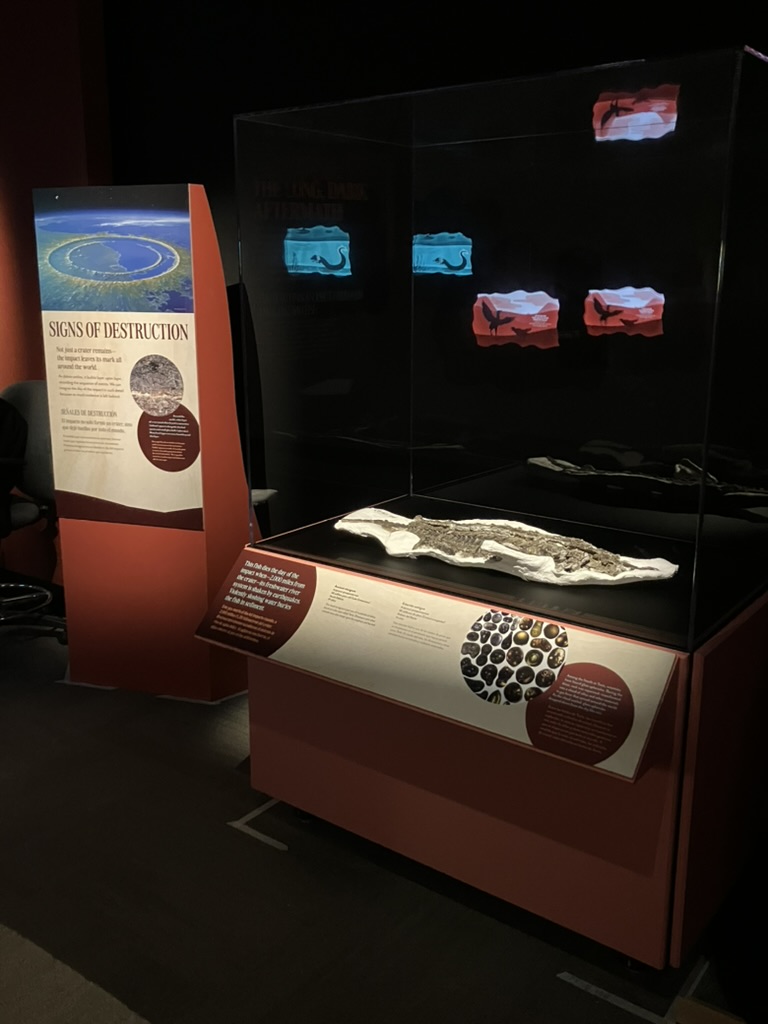

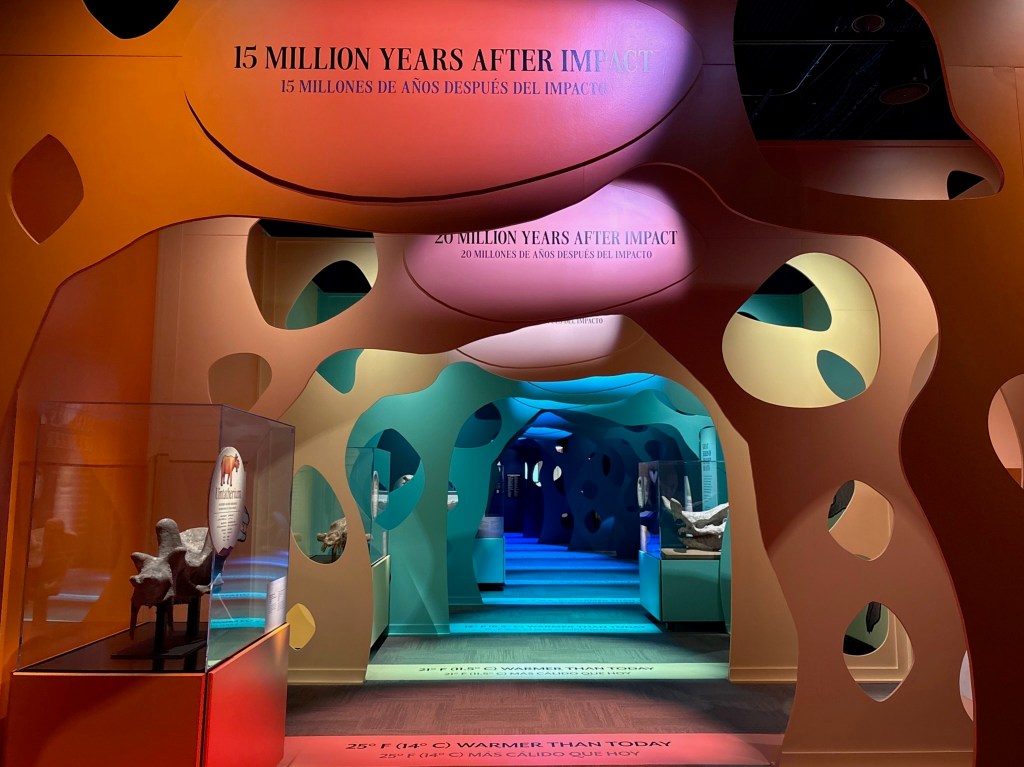

That brings us to After the Age of Dinosaurs. This exhibition is about the immediate aftermath of the end-Cretaceous extinction, and how the world’s ecosystems reassembled after that global catastrophe. But a summary of the subject matter doesn’t fully encapsulate what this show is about. The early Paleogene was famously a time of giant birds and little horses. Taking some inspiration from Alice in Wonderland, we played with the idea that sizes are askew and nothing is as it seems. The exhibition is colorful, whimsical, and full of displays that are just a little weird.

My colleague Marie Georg led the development of this exhibition—I joined a little later on to flesh out and write the second half. Curators Ken Angielczyk and Fabiany Herrera advised on the science, along with nearly a dozen other specialists. Meanwhile, the team worked with Chicago poster artist Jay Ryan to create the look of the show. Jay’s style is bright and bold, with a bit of a pop art feel. He brought those signature qualities to the six murals and nearly sixty standalone illustrations he created for After the Age of Dinosaurs, and the rest of the exhibition’s design follows suit. The result is a paleontology exhibit that looks nothing like the Field Museum’s permanent Evolving Planet, or really any other major fossil exhibit that I’m aware of.

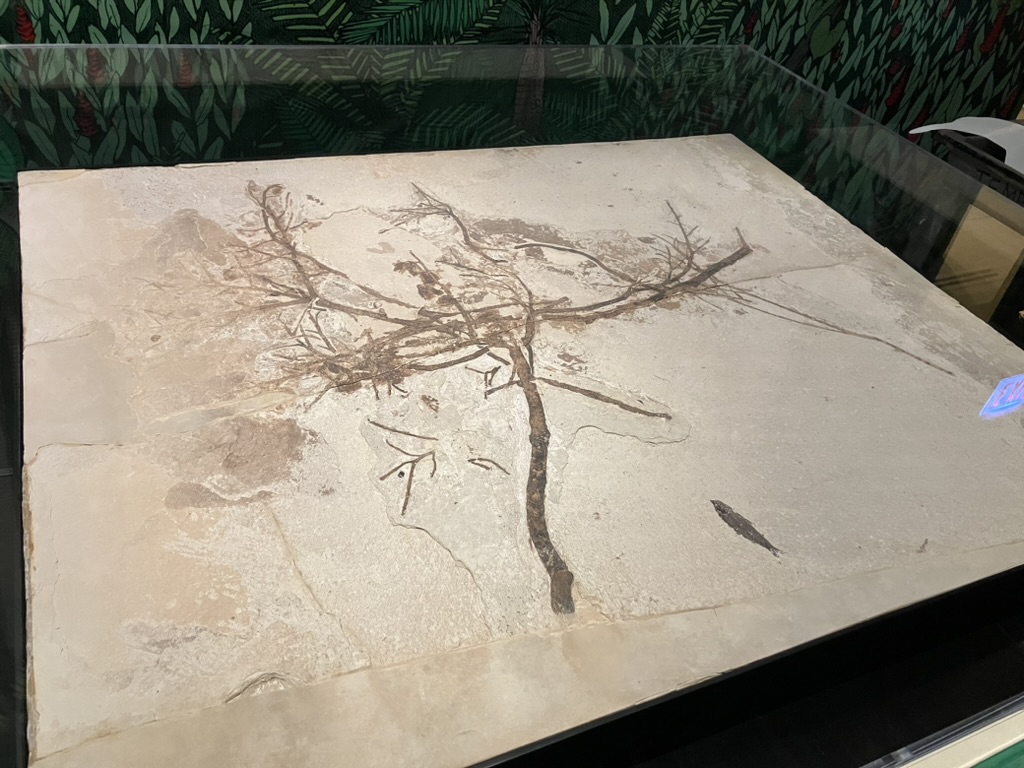

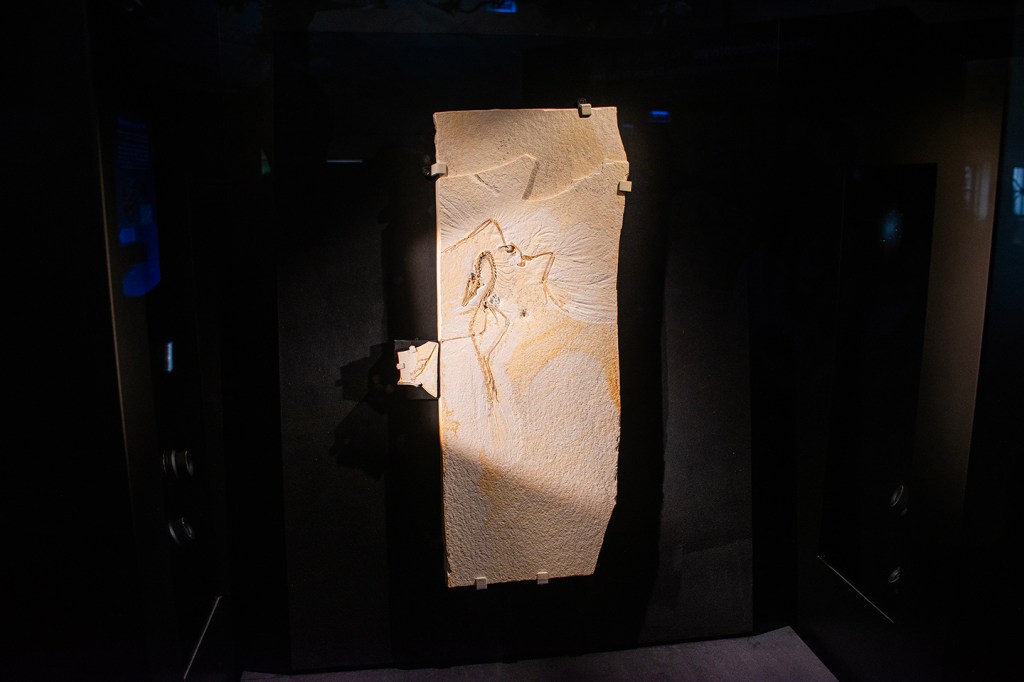

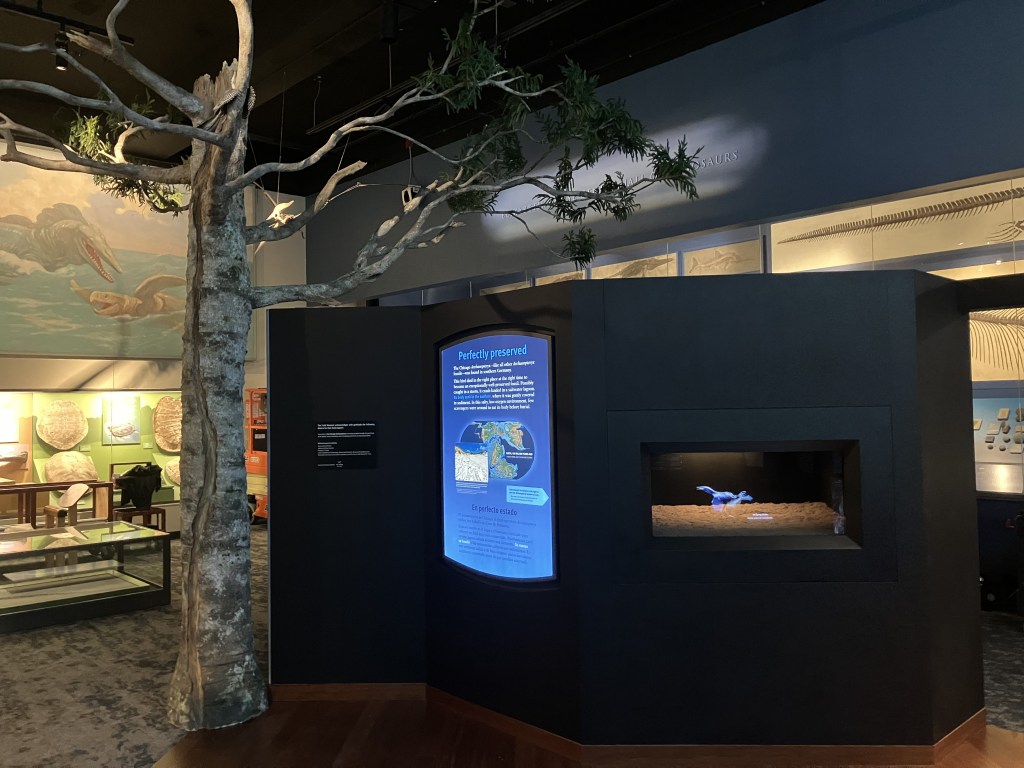

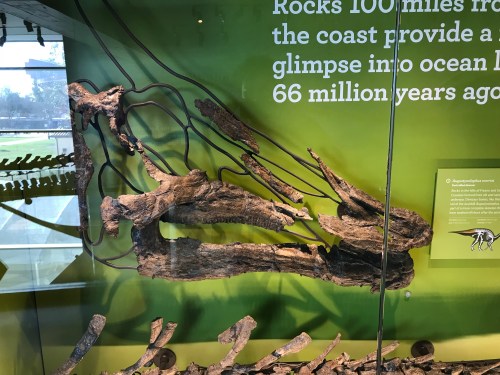

The fossils on display include both brand-new specimens collected during the 2024 field season and classics from the collection that we’d been waiting for an excuse to show off. Visitors can see the largest Megacerops skull ever found, the world’s only known cattail fossil, the oldest grapes from the western hemisphere, a perfectly-preserved passerine bird that was just named this year, and at least four fossils that are in press and so haven’t been formally named yet. The highlight for me is the Diatryma cast skeleton, which was acquired in a trade with the American Museum of Natural History in 1937. This set of disarticulated parts had never made it onto display before, so it was exciting to see it assembled into a standing mount for the first time.

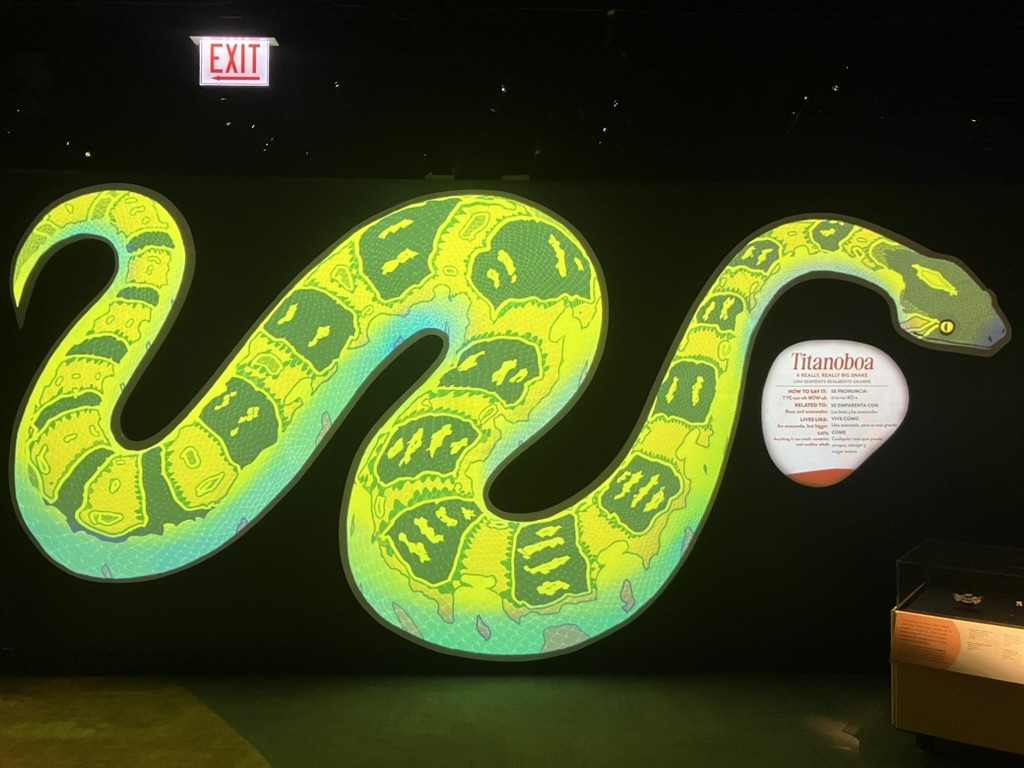

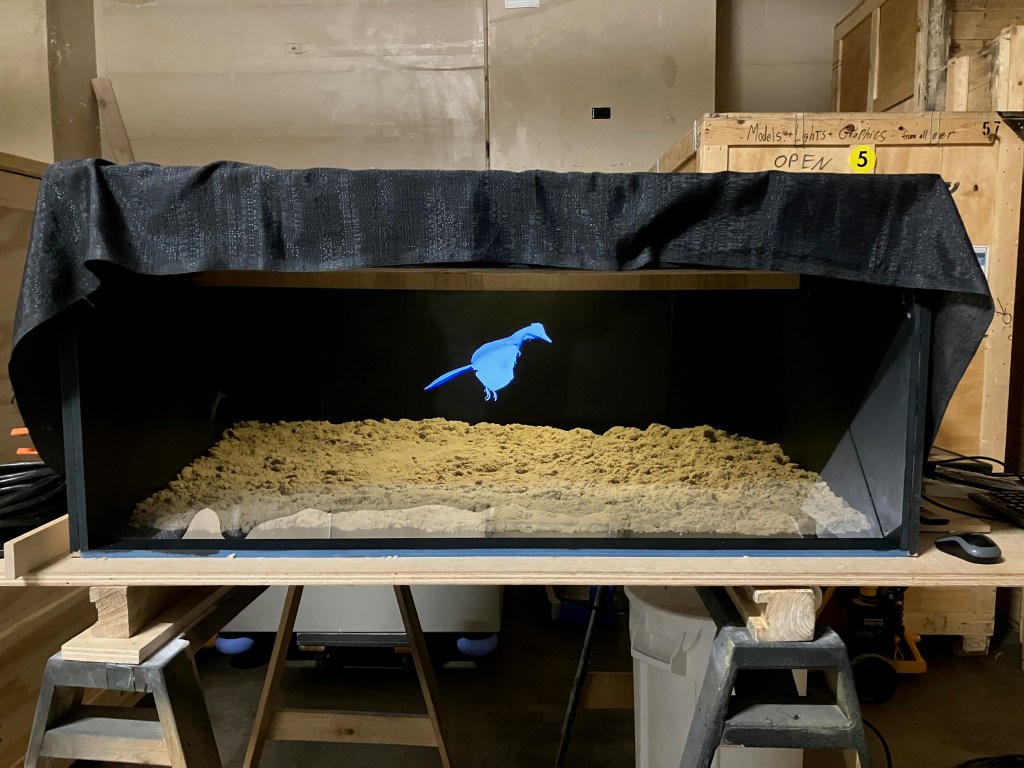

Since so many early Paleogene fossils are on the small side, large media and media-adjacent displays often take center stage. After the Age of Dinosaurs opens with a dramatic presentation of how the asteroid impact devastated global ecosystems, animated in a paper cut-out style by Rachel Oftedahl. A projection of ash billowing through a burnt-out forest adds a somber mood to the next gallery. Look closely at the life-sized projections of pantodonts later in the exhibition and you’ll see their eyes periodically blink. And in the Green River section, visitors can add to the ubiquitous forest soundtrack by standing in spotlights shaped like different animals—these trigger unique sounds that add to the gallery-wide chorus. I’m excited to see how visitors respond to these semi-hidden, playful elements within the exhibition, and how they contribute to the experience overall.

After the Age of Dinosaurs runs until January 2027.