I visited the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) earlier this week, and I need to take a moment to applaud its exceptionally beautiful and well-conceived paleontology hall.

NHMU is part of the University of Utah. It resided in its original home on the Salt Lake City campus from 1969 to 2011, when the museum relocated to a new, purpose-built facility in the foothills near Red Butte Canyon. Several design firms contributed to the Rio Tinto Center (the name for the building in which the museum resides), but the permanent exhibitions—including the paleontology hall—are the work of good ol’ Ralph Appelbaum Associates (RAA). For the unfamiliar, RAA is a dominant player in the field of museum design that is often associated with projects of profound cultural and historic significance, like the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. RAA has fewer natural history projects in its lengthy catalog of commissions. Near as I can tell, their only other paleontology-centric project was the fourth floor fossil halls at AMNH. I’m not a huge fan of many of the design choices made in those halls, so it’s interesting to see what 20 years and a different client can mean.

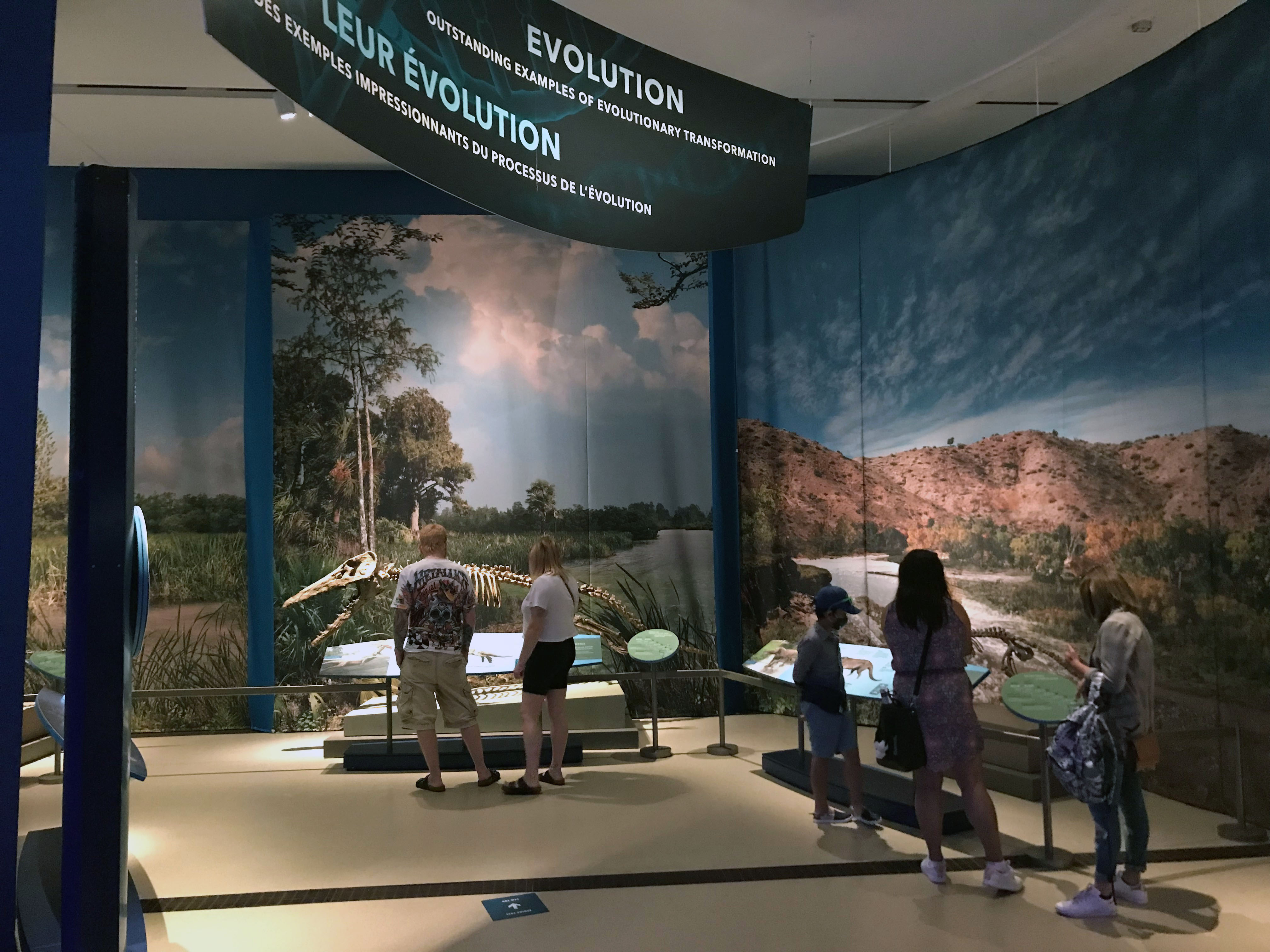

The 44,000 square feet of permanent exhibitions at NHMU flow linearly across the building’s five floors, which visitors can explore from bottom to top or top to bottom. Conceived as a single experience, the exhibitions don’t feel like discreet units—instead, they flow seamlessly into one another as visitors climb or descend along switchbacking paths through the building. I want to call attention to the design of the museum as a whole because it manages to be both stylish and meaningful. Unlike some other museums with bold architecture (looking at you, ROM), the building manages to make a visual statement without hindering visitor experience or usable exhibit space.

The paleontology hall—entitled Past Worlds—occupies about half of the total exhibit space, and fittingly it is the first area visitors encounter if they choose to start at the bottom. The hall is open and spacious, but visitors cannot access the entire exhibition at once. Instead, they follow a zigzagging, switchbacking path, with new sight lines opening up as they go. Monumental elements—namely, the dinosaur skeletons, wall murals, and immersive dioramas—are encountered multiple times from different perspectives.

One example is a life-sized diorama of the lake bottom where fossils of the Green River Formation were preserved. Visitors first see this tableau from an “underwater” perspective. Then, some time later, visitors encounter this same scene again, now looking down from the “surface.” Elsewhere, dinosaur skeletons that can be seen from different vantages are interpreted in multiple ways, depending on what else visitors can currently see and compare them to. This series of reveals and payoffs reminds me of the carefully constructed experiential narratives in theme parks, but precisely applied to help visitors learn about ecology and geology. It’s really cool.

The hall’s color palate is a mix of earth tones and grayscale. Some of this comes from the mounted skeletons, which range from the charcoal gray of Morrison fossils on one end of the space to brown and beige Cretaceous and Cenozoic fossils on the other. Four giant, vertically oriented murals also contribute to the look and feel of the space. Corresponding to the Jurassic, Cretaceous, Paleogene, and Quaternary areas of the hall, these black-and-white murals focus on the flora and landscapes of these eras—you have to look closely to find the animals. I couldn’t find a label identifying the artist, but the murals’ dark foregrounds and bright backgrounds remind me of the original King Kong (or if you want to be fancy, the engravings of Gustav Doré).

As suggested by the murals, the overall space is arranged chronologically. However, the switchbacking path through the exhibition means that visitors start in the recent past and move back to the Jurassic, before reversing direction and moving forward in time. While a time axis is present, Past Worlds is less about presenting a comprehensive narrative of the history of life and more about zeroing in on a few particular ecosystems that once existed in Utah. These include the Morrison Formation of the Jurassic, the Cedar Mountain, Kaiparowits, and North Horn Formations of the Cretaceous, the Green River Formation of the Paleogene, and the recent Ice Ages. These deep dives into specific habitat groups are relatable, digestible, and easy to contrast with one another and the modern world—indeed, I have been not-so-subtly trying to coax the paleontology exhibits at my own institution in the same direction.

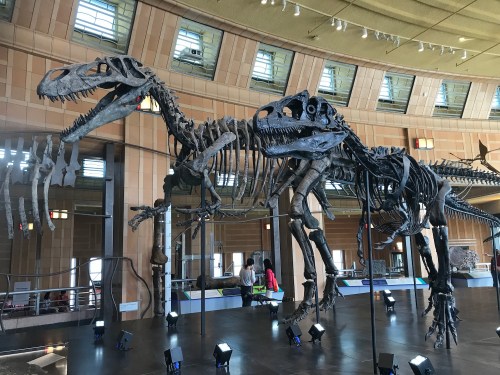

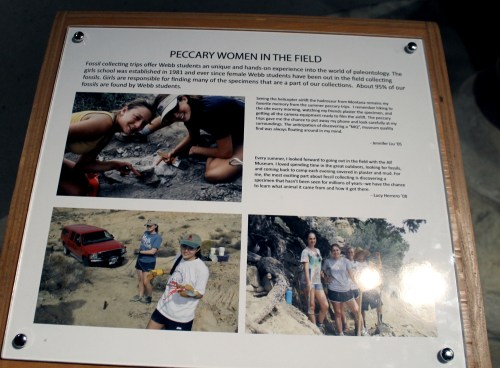

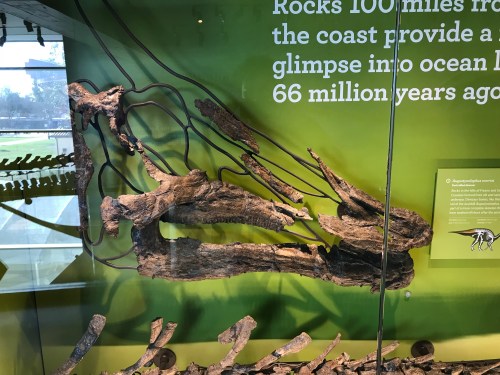

Past Worlds features hundreds of fossil specimens, nearly all from Utah or adjacent states. There are more than 40 mounted skeletons, many of which were firsts for me—I’ve never seen a mounted Marshosaurus, Akainacephalus, or Patriofelis before! Notably, all but one of the standing mounts (the Gryposaurus) are casts. This is not due to a lack of material—most of the mounts are based on fossils from NHMU’s collection. Clearly, somebody made the decision to draw a firm line between the real specimens and the dynamic reconstructions—a line that other museums have traditionally blurred. I think it’s fair for some visitors to be disappointed by this, but using casts allows for some lively and energetic displays. The group of Allosaurus swarming a Barosaurus mired in mud is particularly evocative (and incidentally, the way the sauropod’s tail sweeps under the path and curls overhead is so cool). Besides, there are plenty of real fossils to see, many of which are very strikingly displayed. I was impressed by an in situ hadrosaur skeleton under the floor, which seamlessly merges with a vertical case of Kaiparowits fossils that appears to be rising out of the ground.

Individual labels are commendably brief, and tie each fossil to the larger stories being told. I was pleasantly surprised that the ID lists the discoverer and the preparator of each fossil, when known. Most labels also include a skeletal diagram showing where individual bones fit into the larger skeleton, but these were frustratingly small and almost impossible to make out (a problem shared with similar graphics at NMNH).

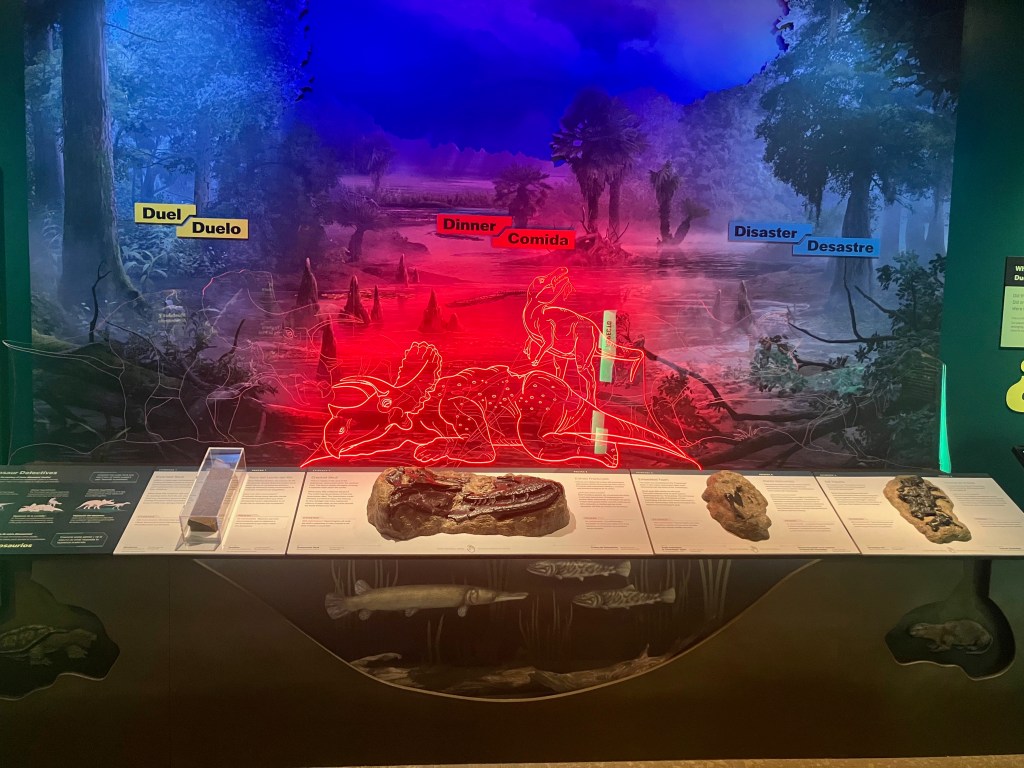

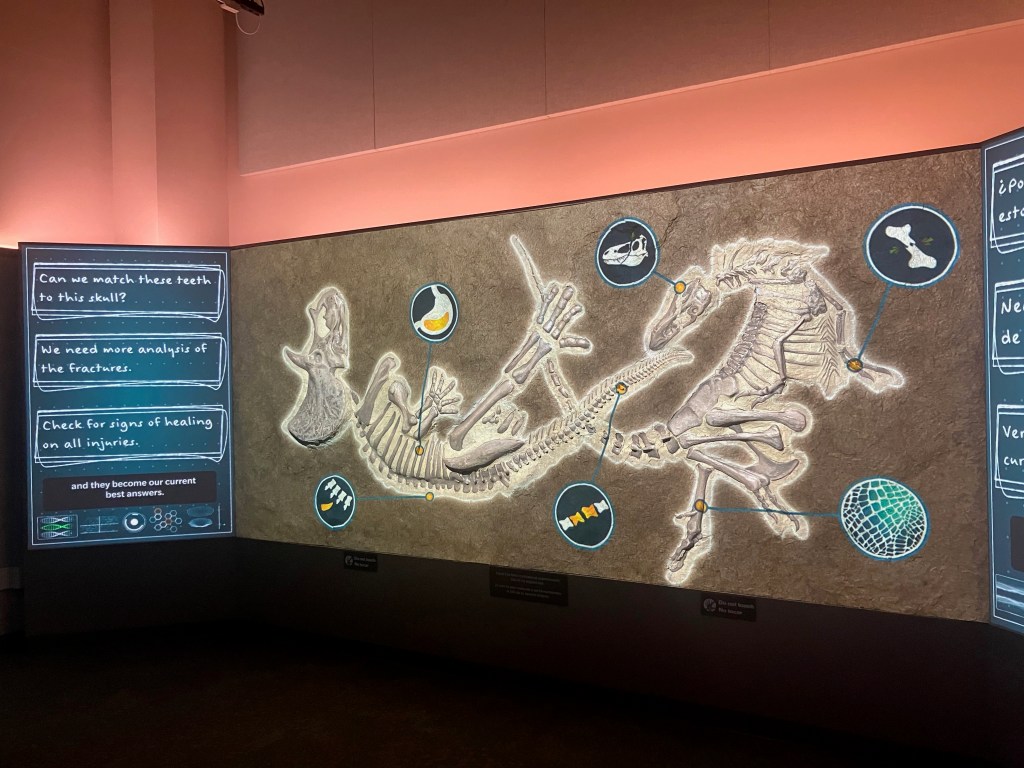

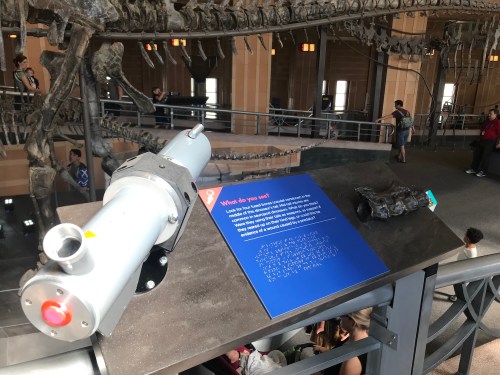

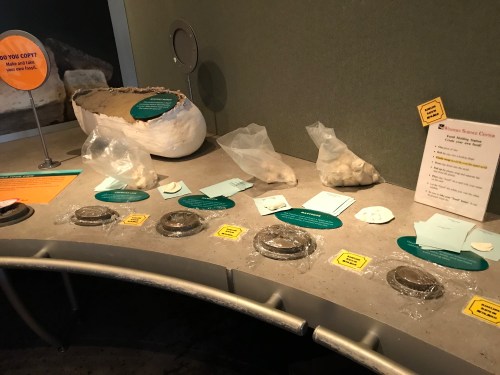

There are plenty of touchable displays, but media is used sparingly. A highlight is a four-part program in which scientists propose different possible causes for the Cleveland-Lloyd assemblage of Jurassic fossils. Visitors are then prompted to vote on which hypothesis is most convincing. The program is several minutes long, but visitors appeared to be staying for the entire thing, and causing a traffic bottleneck in the process.

As you can assuredly tell, I was extremely impressed by NHMU. Meaningful design and a thoughtful approach to visitor experience combine with accessible interpretation and some extraordinary fossils to create a truly outstanding example of a natural history exhibition.