Half a year ago, I promised a series of posts comparing the common strategies for framing the history of life in museum exhibits. This post is the first step toward making good on that goal. Historically, fossil displays at major natural history museums amounted to little more than dinosaur pageant shows, and even today this is all many visitors want or expect. The challenge for exhibit creators is to contextualize the fossils as part of a greater narrative without being alienating, overwhelming, or perhaps worst of all, condescending. A large, permanent exhibit is an enormously time-consuming and expensive undertaking. The opportunity to build or thoroughly renovate an exhibition might occur only once in a generation, so there is exceptional pressure to produce something that succeeds and endures. Exhibits tend to be products of their time, however, and are strongly influenced both by contemporary scholarship and trends in museum theory.

One of the most enduring formats for exploring the fossil record is the “walk through time.” A chronological portrayal of the history of life is an obvious solution, and I don’t mean that in a disparaging way. Audiences are predisposed to understand the forward progression of time, so little up-front explanation is needed. It also helps that the geological timescale compartmentalizes the history of Earth into tidy units. Each Era, Period, or Epoch has a unique cast of characters and a few defining events that make it easy to sum up. There are plenty of examples of chronological fossil exhibits, including Prehistoric Journey at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, The Third Planet at the Milwaukee Public Museum, and even traveling exhibits like Ultimate Dinosaurs. For this post, though, I’ll be using the Field Museum of Natural History’s “Evolving Planet” as my primary case study, since it so thoroughly embraces the “walk through time” format (and I have a good set of photos on hand to jog my memory).

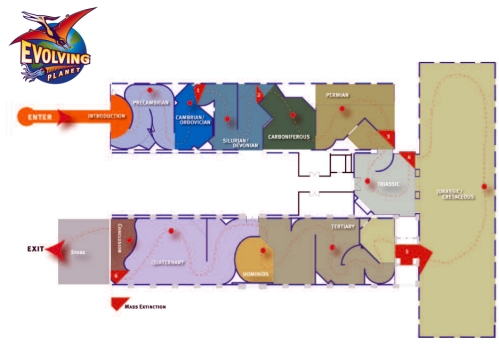

Map of the Field Museum’s Evolving Planet galleries. Source

Evolving Planet is a 27,000 sq. ft. journey through the evolution of life. It opened in 2006, although it is notable that Evolving Planet relies heavily on the structure of the previous paleontology exhibit, “Life Over Time.” Major set pieces like the replicated Carboniferous coal swamp and the Apatosaurus mount remained in place while exhibit designers overhauled the aesthetics and narrative. The most important change is the explicit focus on evolution. Although evolution is key to all biological sciences and the evidence for it is overwhelming, many schools in the United States fail to teach evolution properly and at least a third of the population rejects it outright. As destinations for life-long learning, museums are well-poised to address this deficit in evolutionary understanding, and the Field Museum has enthusiastically risen to the occasion. Evolving Earth weaves the evidence for evolution into all aspects of the displays. The first thing visitors see is the thesis of the exhibit—everything that has ever lived is connected through and is the result of evolution—printed on an otherwise blank wall. Moving forward, visitors learn how evolution via natural selection works, and how we know. Along the way, common misconceptions, such as the idea that lineages improve over time, or that evolution is “just a theory” are proactively addressed and corrected.

This pedagogical approach defines a trend in exhibit design that began in earnest in the 1950s. Early natural history exhibits were designed by and for experts, combining expansive collections of carefully arranged specimens with a few “iconic” displays, such as dinosaur skeletons or taxidermy mounts. By the mid-20th century, however, visitor-centric ideas had begun to take root. Designers began to envision the routes visitors would travel through an exhibit space, and consider what they would look at first when entering a room, and why. Soon hierarchical signage (main ideas in big text, working down to sub-topics and specimen labels) became the norm. Exhibits were enriched with interpretive displays, like dioramas, and scholarly labels were replaced by conversational text and even multimedia. By the 1970s, most of the exhibit responsibilities once held by curators were now handled by exhibit designers and developers. No longer places to explore a collection and view objects at will, exhibits now had carefully structured narratives built around explicit educational goals. In the 80s and 90s, the very floorplans of new exhibits came to reflect this identity, as open halls were replaced with carefully directed switch-backing corridors.

Evolving Planet is, for better or worse, thoroughly rooted in the late 20th century tradition of exhibit design. As the map above shows, once visitors enter Evolving Planet, they are committed to a lengthy trek along a predetermined route. There are no shortcuts to the dinosaurs – you must traverse the entire history of life, starting with its origins in the Precambrian. Along the way, you’ll become familiar with the exhibit’s iconography. Every time you enter a new geologic period, you are greeted by a “Timeline Moment.” These include a chapter heading, a back-lit illustration, an update of where you are on the timeline, and a summation of the key evolutionary innovations and environmental changes of that age. All the walls and graphics in each section are also color-coded, making your progression to each new period very distinct. Finally, the path is occasionally interrupted by unmissable black and red area indicating that a mass extinction has occurred. The resulting experience feels like walking through a book. Information is relayed in a specific order, and visitors are expected to recall concepts that were introduced in previous sections.

A panoramic CGI recreation of the Burgess Shale fauna brings small, easily overlooked fossils to life. Photo by the author.

One challenge inherent to a chronological narrative of the history of life is that the physical evidence for early organisms simply isn’t very interesting to look at (for non-specialists, anyway). Large mounted skeletons of fossil vertebrates have a lot of presence, but they same can’t be said for stromatolites and wiggly-worm impressions. The designers of Evolving Planet address this problem in two ways. First, they built iconic contextual displays to stand in for fossils that aren’t suitably monumental on their own. The Cambrian section features a panoramic animated recreation of the Burgess Shale environment. Actual fossils are available, but the video is what makes visitors stop and take note. Likewise, the Carboniferous section is dominated by a walk-through diorama of a coal swamp, complete with life-sized giant millipedes and dragonflies. Like the predetermined pathway, these landmark displays are very much in keeping with late 20th century trends in exhibit design. It’s a conceptually odd but admittedly effective reversal of the classic museum: fabricated displays are supported by genuine specimens, instead of the other way around.

The second strategy concerns the layout of Evolving Planet, which was inherited from the previous exhibit, Life Over Time. The space is shaped like a U, with switch-backing corridors flanking a more open dinosaur section in the middle. Curator Eric Gyllenhaal explained that “the heavy content, on the stuff that people were not familiar with, was the stuff that came first and came afterward, and that’s where we really got into the details of the evolutionary process” (quoted in Asma, pp. 226-227). Visitors are more focused and more inclined to read signs carefully early in the exhibit, so the developers used the introductory rooms to cover challenging concepts like the origins of life and the mechanisms of speciation. This is the “homework” part of the exhibit, and the narrow corridors and limited sightlines keep visitors engaged with the content, without being tempted to run ahead. Once visitors reach the Mesozoic and the dinosaurs, however, the space opens up. Among the dinosaur mounts, visitors are can choose what they wish to view, and in what order. This serves as a reward for putting up with the challenging material up front. The path tightens up again on the way out, but it’s not as pedagogically rigorous as the beginning of the exhibit. Some sections, like the human evolution displays, are actually cul-du-sacs that can be bypassed by visitors anxious to leave.

Although the dinosaurs get a third of the exhibit to themselves, the hall still struggles to contain them. Photo by the author.

Evolving Planet’s chronological narrative and linear structure complement each other nicely. The sequential path gives the exhibit designers significant control over the visitor’s learning experience, and when dealing with widely misunderstood concepts like evolution, the benefits are clear. The exhibit establishes clear learning goals, and designers can be reasonably confident that these goals are being met. Based on the other new permanent exhibitions at the Field Museum, I get the impression that the design team strongly favors linear exhibits. 2008’s “Ancient Americas”, for instance, closely mirrors Evolving Planet’s structure: a set path through a series of themed spaces, unified by consistent iconography. The designers are to be commended for absolutely owning this concept, and realizing it to its full potential.

Exhibit designers deliberately made the path to the exit much more obvious in the final stretch of Evolving Planet. Photo by the author.

The problem with a linear design, of course, is that it’s constraining. All visitors enter with prior knowledge and a certain worldview or perspective, and are inclined to be more interested in some displays than others. Linear exhibits largely suppress this by forcing everyone through the same tube. Ironically, the strong emphasis on the sequence of geological time periods may also overstate their importance. While these divisions are defined based on real events like extinctions and faunal turnover, they are still human constructs with often messy borders. Relying too heavily on them understates the importance of long-term, short-term, and localized evolutionary events.

Museums should be educational, and exhibits should challenge visitors, particularly regarding the mechanisms of evolution and the scope and complexity of deep time. Still, there’s something to be said for free choice in elective education. Evolving Planet, and “walk through time” exhibits in general, skews more toward the former. It’s an effective option, but also a safe one. Next time, we’ll take a look at exhibits that frame paleontological science in less intuitive ways.

References

Asma, S.T. 2001. Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Diamond, J. and Evans, E.M. 2007. “Museums Teach Evolution.” Society for the Study of Evolution 61:6:1500-1506.

Marsh, D.E. 2014. From Extinct Monsters to Deep Time: An ethnography of fossil exhibits production at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. http://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/50177