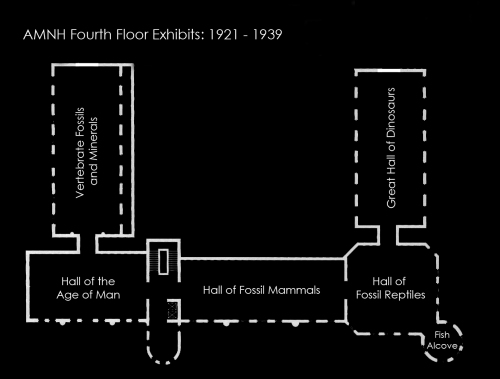

In December 1915, the American Museum of Natural History unveiled the very first mounted Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton, irrevocably cementing the image of the towering reptilian carnivore in the popular psyche. For a generation, AMNH was the only place in the world where one could see T. rex in person. Despite the tyrant king’s fame, old books emphasize the rarity of its fossils. The situation is very different today. In the last 30 years, the number of known Tyrannosaurus specimens has exploded. Once elusive, T. rex is now one of the best known meat-eating dinosaurs, and real and replica skeletons can be seen in museums around the world. The AMNH mount is no longer the only T. rex around, nor is it the biggest or most complete. It was, however, the first, and in a few weeks it will mark the 100th anniversary of its second life. Below is a partially recycled recap of this mount’s extraordinary journey.

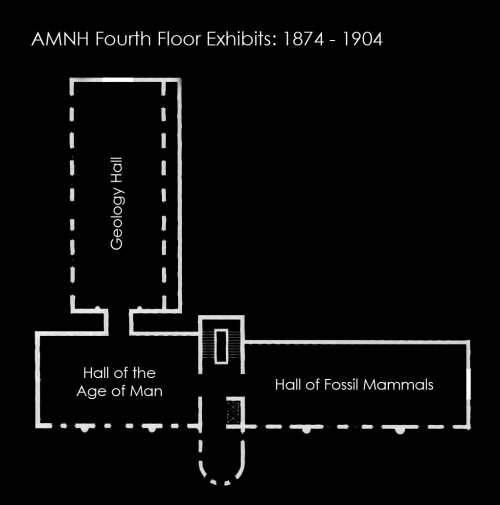

The mount known as AMNH 5027 is actually a composite of material from two individuals. The first is the Tyrannosaurus rex holotype (originally AMNH 973, now CM 9380), which was discovered by Barnum Brown and Richard Lull during an AMNH expedition to Montana in 1902. The find consisted of little more than the pelvis, a single femur, one arm and shoulder, and fragmentary portions of the jaw and skull. Nevertheless, this was enough for AMNH director Henry Osborn to publish a brief description in 1905, as well as coin the species’ brilliantly evocative name. That same year, Adam Hermann prepared a plaster replica of the animal’s legs and pelvis, using Allosaurus fossils as reference when sculpting the missing lower legs and feet. This partial mount was initially displayed alongside the skeleton of a large ground bird, in order to accentuate the anatomical similarities.

Brown located a better Tyrannosaurus specimen in 1908. Apparently fearing poaching or scooping, Osborn wrote to Brown that he wished to “keep very quiet about this discovery, because I do not want to see a rush into the country where you are working.” After vanquishing many tons of horrific sandstone overburden, Brown returned to New York with what was at the time the most complete theropod specimen ever found. In addition to an “absolutely perfect” skull, the new find included most of the rib cage and spinal column, including the first half of the tail (Osborn 1916). Lowell Dingus would later describe this second specimen (the true AMNH 5027) as “a nasty old codger”, suffering from severe arthritis and possibly bone cancer. These pathologies were undoubtedly painful and probably debilitating.

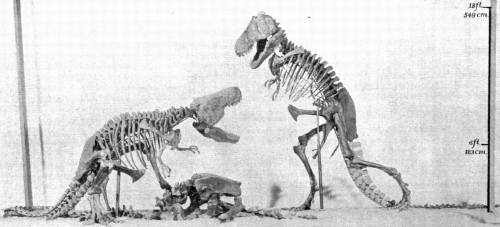

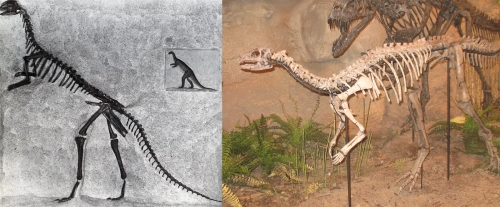

Osborn initially wanted to mount both Tyrannosaurus specimens facing off over a dead hadrosaur. He even commissioned E.S. Christman to sculpt wooden models which which to plan the scene (shown above). However, the structural limitations inherent to securing heavy fossils to a steel armature, as well as the inadequate amount of Tyrannosaurus fossils available, made such a sensational display impossible to achieve. Instead, the available fossils complemented one another remarkably well in the construction of a single mounted skeleton. Osborn noted this good fortune in 1916, but his statement that the two specimens were “exactly the same size” wasn’t quite accurate. The holotype is actually slightly larger and more robust than the 1908 specimen, and to this day the AMNH Tyrannosaurus mount has oversized legs.

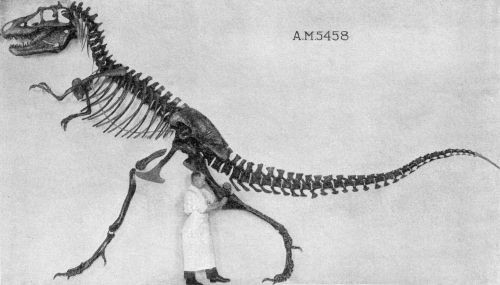

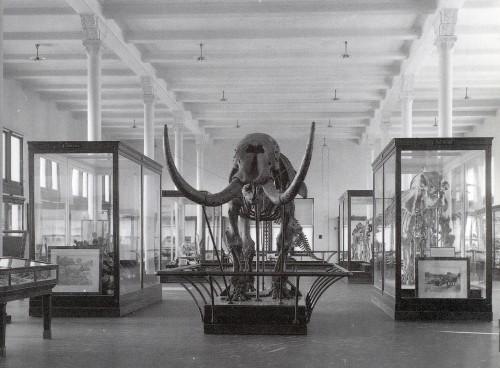

The original Tyrannosaurus rex mount at AMNH. Note the original 1905 replica legs in the background. Photo from Dingus 1996.

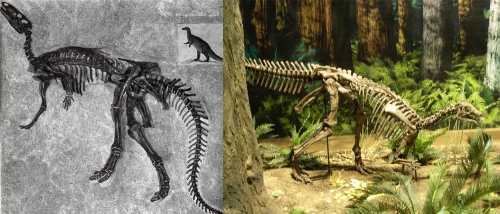

Instead, Hermann’s team prepared a single Tyrannosaurus mount, combining the 1908 specimen with the reconstructed pelvis and legs based on the 1905 holotype. When the completed mount was unveiled in 1915, the media briefly lost their minds. In contemporary newspapers, the skeleton was called “the head of animal creation”, “the prize fighter of antiquity”, and “the absolute warlord of the earth”, among similarly hyperbolic proclamations. Even Osborn got in on the game, calling Tyrannosaurus “the most superb carnivorous mechanism among the terrestrial Vertebrata, in which raptorial destructive power and speed are combined.” With its tooth-laden jaws agape and a long, dragging lizard tail extending its length to over 40 feet, the Tyrannosaurus was akin to a mythical dragon, an impossible monster from a primordial world. This dragon, however, was real, albeit safely dead for 66 million years.

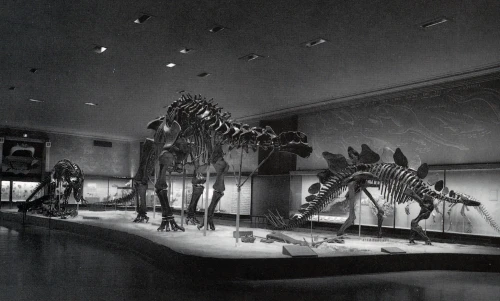

T. rex in the Cretaceous Hall, 1960. Image courtesy of the AMNH Research Library.

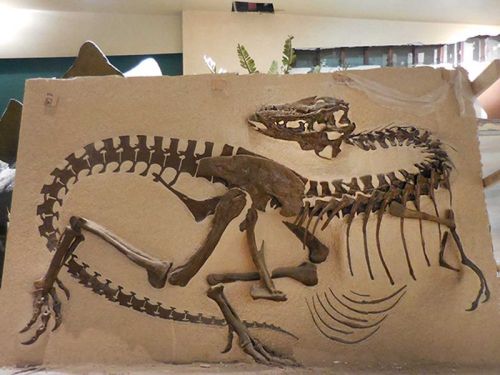

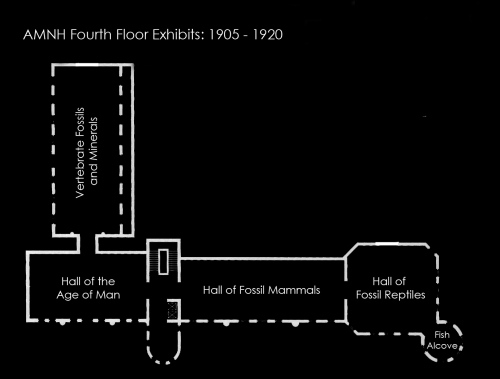

The AMNH’s claim to the world’s only mounted Tyrannosaurus skeleton ended in 1941, when the holotype was sold to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The Pittsburgh museum’s hunch-backed reconstruction of the tyrant king was on display within a year. Although no longer the only T. rex on display, the AMNH mount certainly remained the most viewed as the 20th century progressed. It became an immutable symbol for the institution, visited again and again by generations of museum goers. Its likeness was even used as the iconic cover art of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park.

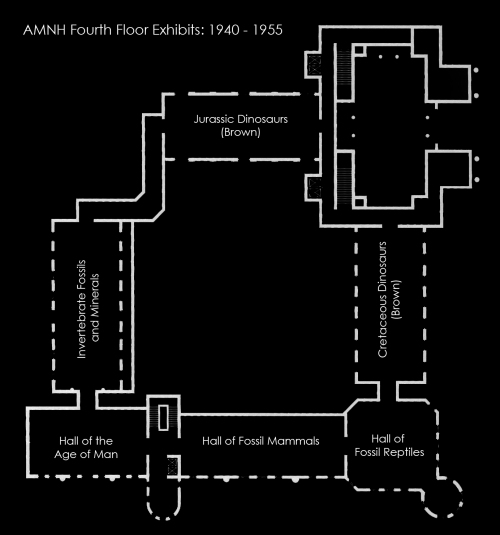

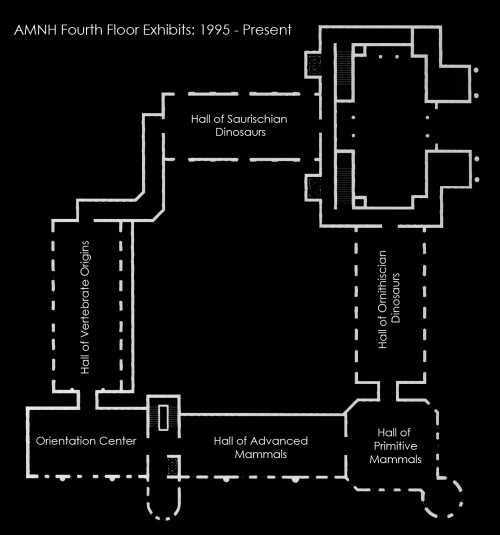

By the 1980s, however, a new wave of dinosaur research had conclusively demonstrated that these animals had been active and socially sophisticated. The AMNH fossil galleries had not been updated since the 1960s, and the upright, tail-dragging T. rex in particular was painfully outdated. AMNH had once been the center of American paleontology, but now its displays were lagging far behind newer museums.

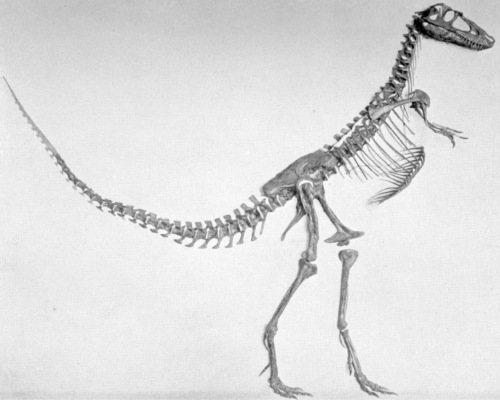

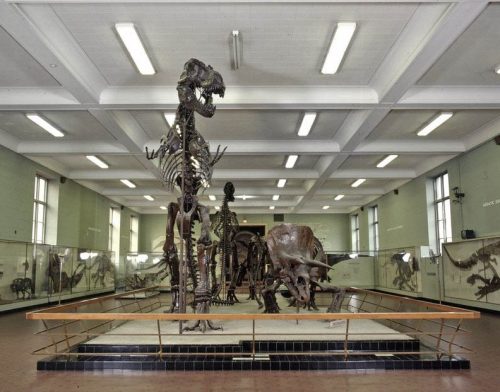

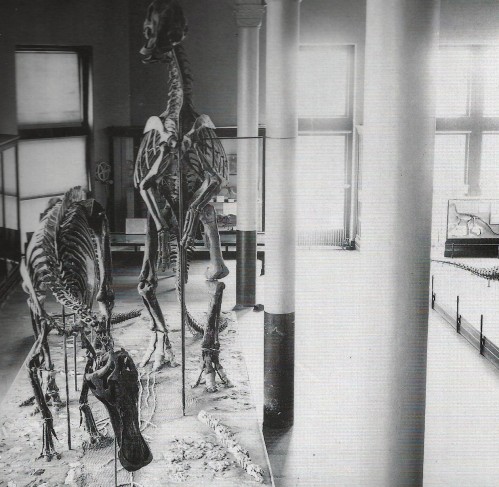

Restoration of AMNH 5027 was completed nearly three years before the hall reopened. Photo from Dingus 1996.

Between 1987 and 1995, Lowell Dingus coordinated a comprehensive, $44 million renovation of the AMNH fossil exhibits. As part of the project, chief preparator Jeanne Kelly led the restoration and remounting of the most iconic specimens, Apatosaurus and Tyrannosaurus. Of the two mounts, the Tyrannosaurus presented the bigger challenge. The fossils were especially fragile, and some elements, specifically the cervical vertebrae, had never been completely freed from the sandstone matrix. It took six people working for two months just to strip away the layers of shellac applied by the original preparators. All told, the team spent a year and a half dismantling, conserving, and rebuilding the T. rex.

Phil Fraley’s exhibit company constructed the new armature, which gave the tyrant king a more accurate horizontal posture. While the original mount was supported by obtrusive rods extending from the floor, the new version is actually suspended from the ceiling by a pair of barely-visible steel cables. Playing with Christman’s original wooden models, curators Gene Gaffney and Mark Norrell settled on a fairly conservative stalking pose, imbuing the mount with a level of dignity befitting this historic specimen. The restored AMNH 5027 was completed in 1992, but would not be unveiled to the public until the rest of the gallery was finished in 1995. Since that time, tens of millions of visitors have flocked to see this new interpretation of Tyrannosaurus. This is the skeleton that showed the world that dragons are real, and it is still holding court today.

References

Dingus, L. 1996. Next of Kin: Great Fossils at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Glut, D.F. 2008. Tyrannosaurus rex: A Century of Celebrity. Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King. Larson, Peter and Carpenter, Kenneth, eds. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

McGinnis, H.J. 1982. Carnegie’s Dinosaurs: A Comprehensive Guide to Dinosaur Hall at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Institute. Pittsburgh, PA: The Board of Trustees, Carnegie Institute.

Norell, M, Gaffney, E, and Dingus, L. 1995. Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Osborn, H.F. 1906. Tyrannosaurus, Upper Cretaceous Carnivorous Dinosaur: Second Communication. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History vol. 22, pp. 281-296.

Osborn, H.F. 1913. Tyrannosaurus, Restoration and Model of the Skeleton. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History vol 32, pp. 9-12.

Osborn, H.F. 1916. Skeletal Adaptations of Ornitholestes, Struthiomimus, and Tyrannosaurus. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History vol 35, pp. 733-771.