Click here to start the NMNH series from the beginning.

Some time ago, I wrote about the O.C. Marsh dinosaurs at the National Museum of Natural History. These are the mounted skeletons made from the enormous collection of fossils Marsh accumulated while working for the United States Geological Survey – if you’d like, you can catch up with Part 1 (on Edmontosaurus and Triceratops) and Part 2 (on Camptosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Stegosaurus). Looking back, I noticed that I never actually finished, so here are the two Marsh dinosaurs with as-yet untold stories.

The Thescelosaurus

The name Thescelosaurus neglectus means “neglected wonderful lizard”, because Smithsonian paleontologist Charles Gilmore found the original specimen at the bottom of a crate, more than 10 years after it arrived at NMNH. Still buried its its field jacket, this skeleton had been long overlooked by both Marsh and the museum staff. Nevertheless, Gilmore found that it was remarkably complete and that it represented a taxon new to science.

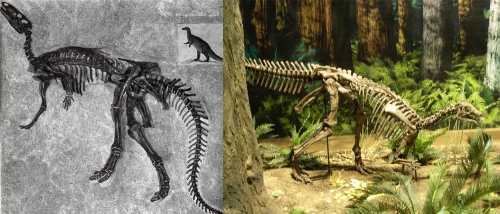

An illustration of the Thescelosaurus holotype prior to reconstruction. Source

The specimen that would become the Thescelosaurus holotype (USNM 7757) was excavated by John Bell Hatcher and William Utterback in July of 1891, while they were collecting for Marsh in Niobrara County, Wyoming. 20 years later, Gilmore discovered that the skeleton was articulated and intact, save for the head, neck, and parts of the shoulder. He even found small patches of preserved skin on the tail and legs. According to Gilmore, the animal had been buried rapidly after death, since it showed no signs of dismemberment by scavengers.

After describing the fossils, Gilmore mounted the Thesclosaurus in relief on its left side. Other than the reconstructed skull (modeled after Hypsilophodon), the specimen was displayed almost exactly as it was found. This was important to Gilmore, because as he wrote in his published description, “I am…of the opinion that specimens so exhibited hold the attention of the average museum visitor far longer and arouse a keener interest in the genuineness of the specimen than does a skeleton that has been freed from the rock and mounted in an upright, lifelike posture.” Today at least, I suspect that the opposite is true – visitors are generally more impressed by dynamic standing mounts than by reliefs that preserve death poses. Still, it’s fascinating to gain a small amount of insight into the motivations of a pioneering mount-maker.

Although it was first displayed in the Hall of Extinct Monsters, the Thescelosaurus was most prominently exhibited in the 1963 version of the NMNH fossil halls. Here, it joined the Edmontosaurus, Gorgosaurus, and partial Corythosaurus relief mounts along the south wall. In life, these animals were vastly removed from one another in time and space, but displayed together they almost appeared to be parts of a single quarry face. The Thescelosaurus moved to the north wall in 1981, unfortunately placed rather high and out of most visitors’ line of sight.

Thescelosaurus cast in the RCI workshop. Source

Close-up of the new Thescelosaurus skull. Source

When the new National Fossil Hall opens in 2019, USNM 7757 will be replaced with a duplicate cast. The original bones will be moved to the collections, where they can be properly studied for the first time in a century. Already, technicians at Research Casting International have freed the skeleton’s left side, which had never been fully prepared. The exhibit replica assembled by RCI is beautiful, retaining the ossified tendons and cartilage impressions of the original. Mounted in a running pose, the new cast also features an updated head, based on Clint Boyd’s recent description of Thescelosaurus cranial anatomy.

The Allosaurus

Built in 1981, the Allosaurus fragilis (USNM 4734) was the last Marsh Collection dinosaur to be mounted, although bits and pieces have been on display at NMNH since 1920. There has been considerable interest in this individual recently, in part because Kenneth Carpenter and Gregory Paul proposed in 2010 that it become the neotype for Allosaurus – more on that in a moment. Others are interested in this specimen because of its unique pathologies. In addition to several broken and healed bones, the Allosaurus has a massive puncture wound on its left scapula, which nicely matches the diameter of a Stegosaurus tail spike.

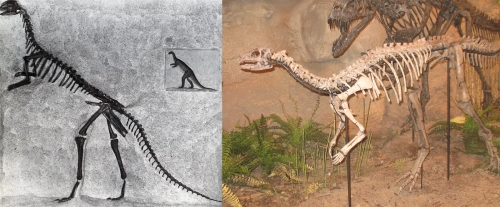

Benjamin Mudge collected this specimen in 1877 near Cañon City, Colorado. Known as the Garden Park quarry, this site also produced the Stegosaurus, Camptosaurus, and Ceratosaurus on display at NMNH. Although the Smithsonian obtained the Allosaurus with the rest of the Marsh Collection around 1900, Gilmore did not look at it (or any of the theropod material) until at least 1911. All told, USNM 4734 consists of a partial skull and jaw, a complete set of presacral and sacral vertebrae, a few ribs, a pelvis, and virtually complete arms and legs. It would have had a tail as well, but Mudge’s crew accidentally threw the articulated tail over a cliff while excavating the skeleton. Norman Boss assembled a reconstructed skull, which was displayed through the 1970s. The articulated legs and feet were exhibited in a free-standing case until the late 1950s.

This specimen’s taxonomic history merits some discussion. The holotype Marsh selected when naming Allosaurus (YPM 1930) is notoriously poor, consisting of a single phalanx, two dorsal centra, and a tooth. Dozens of very complete skeletons attributed to Allosaurus are now known, and most specialists basically agree on what an Allosaurus is, but the lack of a usable type with which to define the taxon has been an ongoing problem.

The far more complete USNM 4734 was recovered from the same quarry as the Allosaurus holotype, during the same 1877 field season. Marsh himself actually used this specimen, rather than his designated type, to illustrate subsequent publications on Allosaurus. In 1920, Gilmore flirted with the idea of nominating USNM 4734 as a neotype for Allosaurus, but for reasons that I find difficult to follow, he decided to lump both specimens into the older name Antrodemus valens. Joseph Leidy coined Antrodemus in 1870 based on a single caudal vertebra with no geologic provenance, so this move did little to fix the underlying issue. Nevertheless, Antrodemus remained a popular synonym for Allosaurus in some circles for several decades.

Arnold Lewis rebuilds the Allosaurus skull in 1979. Image from Thomson 1985.

When the NMNH fossil halls were renovated in 1981, the designers noticed that the exhibit badly needed a large theropod mount. Arnold Lewis was tapped to design and construct a complete mounted version of USNM 4734, with some assistance from Ken Carpenter. The tail was cast from a Brigham Young University specimen, but Lewis sculpted the belly ribs and sternum using an alligator skeleton as reference. The completed Allosaurus measures 17 feet from its grinning jaws to the tip of its tail, and a form-hugging armature makes it look particularly dynamic. This mount has been a favorite among visitors for more than 30 years, although the 2001 addition of a Stan the Tyrannosaurus cast has somewhat overshadowed the smaller theropod.

Technicians from Research Casting International took down the Allosaurus in the summer of 2014 as part of the current round of renovations. You can watch a video of the de-installation here. The skeleton will be remounted in a few years (crouching beside a nest mound), but Smithsonian researchers want to get a good look at it before that happens. In particular, curator Matt Carrano has been wondering for some time whether a partial jaw Marsh named “Labrosaurus ferox” actually belongs to this specimen. The “Labrosaurus” jaw, which has an unusual pathology caused by a bite or twisting force, came from the same quarry as USNM 4734, and appears to be the same portion of jaw that the more complete skeleton is missing. Time will tell whether Carrano’s hunch is correct. Meanwhile, Carpenter and Paul’s petition to replace the Allosaurus type with this more complete specimen from the same locality is still pending. We should expect to hear more about that soon, as well.

References

Carpenter, K., Madsen, J.H., and Lewis, L. (1994). Mounting of Fossil Vertebrate Skeletons. Vertebrate Paleontological Techniques. 285-322.

Gilmore, C. M. (1915). Osteology of Thescelosaurus, an ornithopodus dinosaur from the Lance Formation of Wyoming. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum 49:2127:591–616.

Gilmore, C.M. (1920). Osteology of the Carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum with Special Reference to the Genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus. United States National Museum Bulletin 110:1-154.

Lee, J.J. (2014). The Smithsonian Disassembles its Dinosaurs. National Geographic Online. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/07/140731-dinosaur-hall-smithsonian-renovation-culture-science/

Paul, G.S. and Carpenter, K. (2010). Allosaurus Marsh, 1877 (Dinosauria, Theropoda): proposed conservation of usage by designation of a neotype for its type species Allosaurus fragilis Marsh, 1877. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 67:1:53-56.

Thomson, P. (1985). Auks, Rocks, and the Odd Dinosaur: Inside Stories from the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Thomas Y. Crowell.