Click here to start the Extinct Monsters series from the beginning.

More than 80 years ago, Smithsonian paleontologist Charles Whitney Gilmore supervised the installation of the mounted Diplodocus skeleton known as USNM 10865. In December 2014, that same skeleton was finally disassembled for conservation and eventual re-mounting.This post is about the history of this particular mount: where it came from, who put it together, and what it has and continues to tell us about prehistory.

Predecessor at CMNH

The story of the NMNH Diplodocus mount actually began in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania around the turn of the century. In November of 1898, Steel tycoon-turned-philanthropist Andrew Carnegie read that the remains of a giant “Brontosaurus” had been discovered in Wyoming. Carnegie’s interest was piqued and the following year, he contributed $10,000 to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (which he had founded two years earlier) to find a complete “Brontosaurus” – or something like it – for display in Pittsburgh. Perhaps proving that money can indeed buy anything, on July 4th, 1989 the CMNH team found a reasonably complete sauropod skeleton in Sheep Creek Basin, Wyoming. CMNH Curator of Paleontology John Bell Hatcher declared the specimen to be a new species, which he named for the Museum’s benefactor: Diplodocus carnegii.

Back in Pittsburgh, the task of preparing and mounting the fossils fell to preparator Arthur Coggeshall and his staff. Creating a permanent armature for a delicate 84-foot skeleton was a monumental undertaking, beyond anything that had ever been attempted before. Coggeshall used a steel rod, shaped to the contours of the vertebral column, as the basis for the mount. Once the backbone was in place, the limbs, ribs, and other extremities were mounted on steel rods of their own and attached to the rest of the skeleton. The fossils were connected to the steel armature by drilling screws and bolts directly into the bone. Since the original Diplodocus carnegii skeleton was not complete, the mount was supplemented with fossils uncovered during subsequent field seasons at Sheep Creek and elsewhere in Wyoming.

The CMNH Diplodocus was unveiled in 1907 in a brand-new wing that had been constructed to display it. Although the American Museum of Natural History had by that point completed a sauropod mount of their own, the Pittsburgh display was well-received by paleontologists and laypeople alike. Not to be bested by the New York competition, Carnegie also commissioned eight Diplodocus replicas, which he donated to museums throughout Europe and Latin America.

The original CMNH Diplodocus mount, in the hall built specifically to accommodate it. Source

This wave of publicity allowed the paleontology staff at CMNH and elsewhere to continue to undergo large-scale fossil hunting expeditions. In 1909, a team led by Earl Douglass hit the jackpot north of Jensen, Utah. At the site now known as Dinosaur National Monument, CMNH teams excavated over 300 tons of Jurassic fossils over 13 field seasons. The immensely productive “Dinosaur Quarry” site is thought to represent a prehistoric river bar, where dead animals from upsteam accumulated over time. In addition to an assortment of crocodiles and other small reptiles, this location has yielded remains of Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, Allosaurus and many other taxa. Although the site was far from exhausted, the CMNH team moved on in 1922, at which point paleontologist Charles Gilmore from the United States National Museum took over.

USNM Excavation at Dinosaur National Monument

Gilmore led the first USNM field season at Dinosaur National Monument in May of 1923. In their final year at the site, the CMNH team had located two partial sauropod skeletons. Gilmore opted to focus on excavating these “in order to secure a mountable skeleton” for display (Gilmore 1932). As with the CMNH team before them, the primary motivation of Gilmore’s team was not scientific research, but to bring back spectacular display specimens. Gilmore was unarguably a phenomenal scientist who made lasting contributions to our knowledge about prehistory, but this focus on impressive displays was typical of early 20th century paleontology. As such, valuable taphonomic and ecological data that would been collected by modern paleontologists was probably destroyed when unearthing this and other exhibition-caliber dinosaur specimens.

Once the excavation began, Gilmore decided that the Diplodocus skeleton dubbed specimen 355 was the best candidate for a mount. The skeleton consisted of an articulated vertebral column, from the 15th cervical to the 5th caudal, a separated but virtually complete tail, the pelvis, both pectoral girdles, much of the rib cage, both humeri, and a complete left hind limb. Unfortunately, the head and most of the neck had eroded out of the hillside and long since weathered away. Some elements not preserved with specimen 355 were reportedly cherry-picked from another specimen at the same site. Again, this sort of selective excavation is discouraged today, but was typical at the time. On August 8, the team wrapped up and shipped 25 tons of material back to Washington, DC via railway.

Preparation, Mounting and Description

Preparing and mounting the Diplodocus was, according to Gilmore, the single most ambitious undertaking attempted by the department during his tenure. In his words, “the magnitude of the task, by a small force, of preparing one of these huge skeletons for public exhibition can be fully appreciated only by those who have passed through such an experience” (Gilmore 1932). Gilmore, along with preparators Norman Boss, Thomas Horne, and John Barrett, spent 2,545 working days over the course of six years preparing the skeleton for exhibition. Gilmore reported that his team followed the method Arthur Coggeshall had developed at CMNH over 20 years earlier for mounting their sauropod. The vertebral column was assembled first, supported by a series of steel rods. This structure was mounted at the appropriate height on four upright steel beams securely anchored to the floor. Limbs and other extremities were subsequently added, with steel rods shaped to the contours of the fossils supporting each portion of the skeleton.

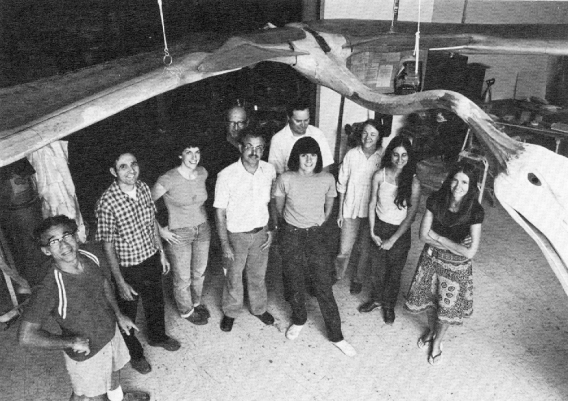

Diplodocus under construction, ca. 1930. Source

Missing parts of the skeleton, including the right hindlimb and the distal portions of the forelimbs, were filled in using casts of the Carnegie Diplodocus. According to Gilmore, the casted elements were colored “to harmonize with the actual bones but with sufficient difference to be at once distinguished from the originals” (Gilmore 1932). This is noteworthy, because the creators of other dinosaur mounts at that time had been known to deliberately disguise artificial elements by painting them to match the fossils. Although the Smithsonian Diplodocus was a composite of multiple specimens and therefore does not represent any single animal that actually existed, the decision to make the casted elements readily visible represents a degree of honesty and integrity that is more common in modern museum displays than it was in Gilmore’s time.

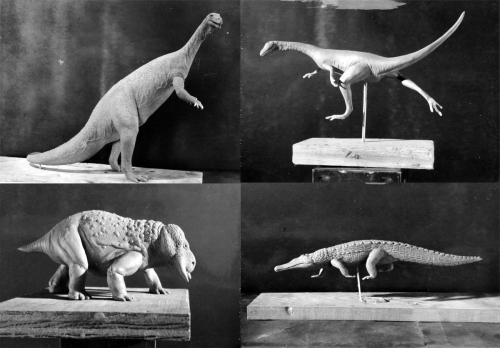

Gilmore presents plans for the in-progress Diplodocus mount at the 1927 Conference of the Future of the Smithsonian. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

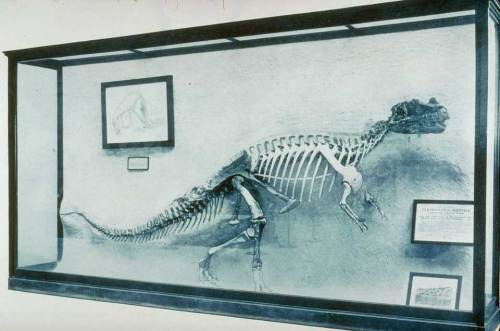

In the process of preparing and mounting the Diplodocus (at this point designated USNM 10865), Gilmore was able to further refine our understanding of sauropod physiology. Looking at the specimen, Gilmore was easily able to dismiss notions by earlier workers that Diplodocus had sprawled like a crocodile, asserting that “the crocodilian attitude for Diplodocus involves anotomical imposibilities” (Gilmore 1932). Additionally, since the entire dorsal portion of the vertebral column was present and intact, Gilmore determined that the presacral vertebrae (in the lower back) arch downward, toward the sacrum. The CMNH Diplodocus and AMNH Apatosaurus had been mounted with completely straight backs, so Gilmore was able to create a more accurate mount. Studying the articulated vertebral column also convinced Gilmore to raise the tail higher than in previous sauropod mounts. Although it would be decades before paleontologists started raising the tail completely clear of the ground, this was certainly a step in the right direction. Gilmore refrained, however, from definitively assigning USNM 10865 to a particular species of Diplodocus, since at the time (and to this day, apparently) the differences among the named species of this genus were unclear.

Exhibition and Legacy

The completed Diplodocus skeleton was 70 feet, 2 inches long and 12 feet, five inches tall at the hips, making it about 14 feet shorter in length than its CMNH counterpart. The mount was introduced to the Hall of Extinct Monsters at the United States National Museum in 1931, positioned atop three pedestals so that visitors could walk right underneath it. The Diplodocus was placed right in the center of the gallery, facing west so that it could stare down visitors as they entered the hall.

The unveiling of the Diplodocus mount was a big deal, but did not catch the public’s attention in quite the same way as its CMNH predecessor. After all, by 1931 several of the other major natural history museums had had sauropods on display for over two decades. Nevertheless, for residents and visitors in Washington, DC the new mount was an unforgettable look at the life of the past.

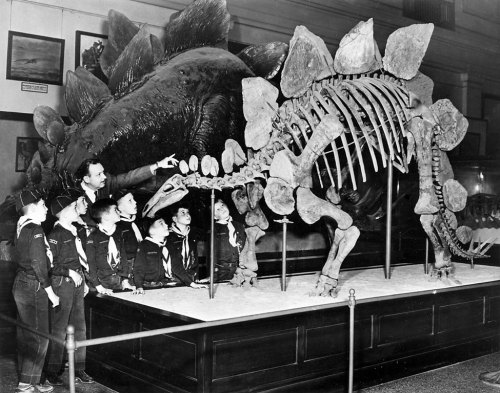

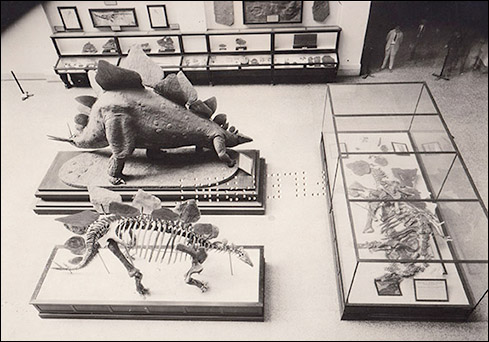

The Diplodocus was not moved during the 1963 modernization of the fossil exhibits, but the walkable area around the mount was significantly reduced. Visitors could no longer walk under the skeleton, or get as close to it. The Diplodocus was not moved during the 1981 renovation, either, but the neck support coming up from the floor was replaced by less intrusive cables suspended from the ceiling. In the new exhibit, the sauropod centerpiece was surrounded by contemporaneous friends from the Morrison Formation, including Stegosaurus, Camptosaurus, Camarasaurus and Allosaurus.

Diplodocus as it stood from 1981-2014. Photo by the author.

From 1931 to 2014, the Diplodocus remained an unchanging fixture of the Museum’s east wing. Although this specimen’s story has not been as widely told as that of the CMNH Diplodocus, the Smithsonian sauropod is certainly just as interesting. For more than 80 years, USNM 10865 has mesmerized generations of viewers with its size and elegance. What’s more, this specimen, and the associated measurements and drawings meticulously prepared by Gilmore, are frequently referred to in publications by modern paleontologists. For its contributions to public education and to scientific inquiry, USNM 10865 is one to celebrate.

References

Brinkman, P.D. The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush: Museums and Paleontology in America at the Turn of the 20th Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Gilmore, C.W. “On a Newly Mounted Skeleton of Diplodocus in the United States National Museum.” Proceedings of the United States National Museum 81:1-21, 1932.

Gilmore, C.W. “A History of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology in the United States National Museum.” Proceedings of the United States National Museum 90, 1941.