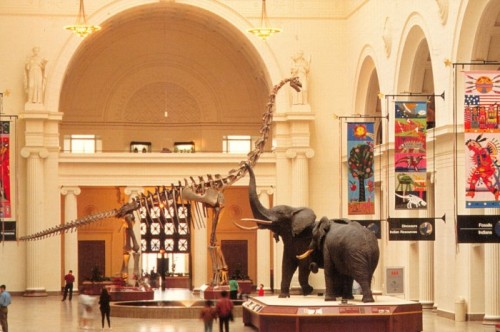

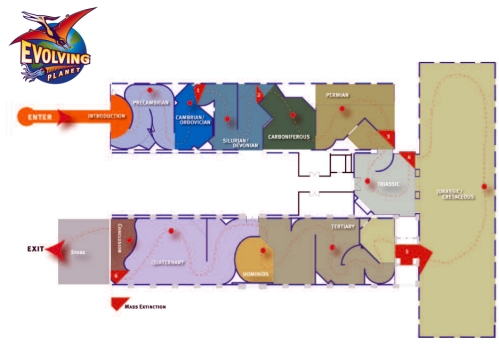

In April 2014, the paleontology exhibits at the National Museum of Natural History closed for a wall-to-wall renovation. The re-imagined National Fossil Hall will reopen in 2019. We are now approaching the halfway point of this journey, which seems like a fine time to say farewell to some of the more charismatic specimens that are being rotated off display.

In comparison to the old exhibit, the new version will be influenced by a less-is-more design philosophy. While there will not be quite as many individual specimens on display, those that are included will be more visible and will be explored in more detail. This combined with the significant number of new specimens being added means that many old mainstays had to be cut from the roster. Cuts occur for a variety of reasons, including eliminating redundancy, preserving specimens that were not faring well in the open-air exhibit space, and making specimens that have been behind glass for decades available to a new generation of researchers. Retired specimens are of course not going far – they have been relocated to the collections where students and scientists can study them as needed.

Stegomastodon (USNM 10707)

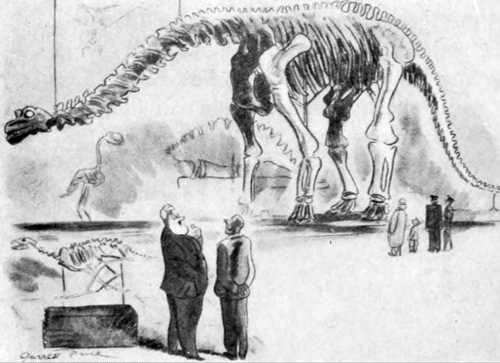

The young male Stegomastodon is the largest single specimen that is being retired from the NMNH fossil halls. James Gidley and Kirk Bryan collected this skeleton in the San Pedro Valley of Arizona, during the same 1921 collecting trip that produced the museum’s Glyptotherium (which will be returning). While the genus Stegomastodon was erected in 1912, Gidley referred his specimen to a new species, S. arizonae, due to its more “progressive” physiology and slightly younger age. By 1925, the skeleton was mounted and on display in the Hall of Extinct Monsters. While the original mount used the real fossil tusks, these were eventually replaced with facsimiles.

There are at least two reasons the Stegomastodon will not be returning in 2019. First, there are already two big elephants on display: the mammoth and the mastodon. Elephants take up a lot of space, and a third proboscidean offers diminishing returns when compared to the amount of floor space it requires. More importantly, the Stegomastodon is a holotype specimen, and the exhibit team elected to remove most of these important specimens from the public halls. This is both to keep them safe from the damaging effects of vibration, humidity, and fluctuating temperature, as well as to make them more accessible to researchers.

Paramylodon (USNM V 15164)

Collections staff wheel Paramylodon out of the exhibit hall. Source

During the 1960s, Assistant Curator Clayton Ray oversaw the construction of the short-lived Quaternary Hall, which was reworked into the Hall of Ice Age Mammals. This meant creating a number of brand-new mounts, including several animals from the Rancho La Brea Formation in Los Angeles County. La Brea fossils are not found articulated, but as a jumble of individual elements preserved in asphalt. The Los Angeles Natural History Museum provided NMNH with an assortment of these bones, which preparator Leroy Glenn assembled into two dire wolves, a saber-toothed cat, and the sheep cow-sized sloth Paramylodon.

Paramylodon is another cut for the sake of eliminating redundancy: the colossal Eremotherium completely overshadows this more modestly-sized sloth. This mount also needed some TLC. For aesthetic reasons, the Paramylodon was given an internal armature, which involves drilling holes through each of the bones. Last year, preparator Alan Zdinak took on the task of disassembling and conserving these damaged fossils with assistance from Michelle Pinsdorf.

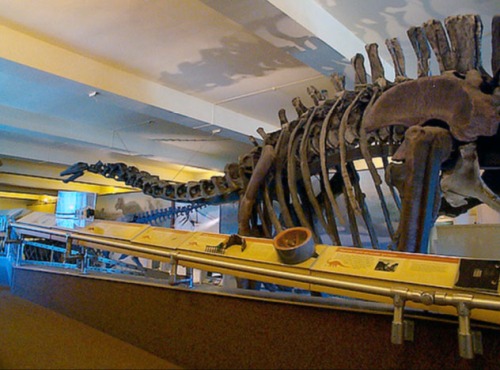

Zygorhiza (USNM PAL 537887)

Zygorhiza cast in the Life in the Ancient Seas gallery. Source

When the Life in the Ancient Seas gallery opened in 1990, it featured a historic Basilosaurus skeleton that had been on display since the 1890s. This ancestral whale was relocated to the Ocean Hall in 2008, and a cast of the smaller whale Zygorhiza took its place in Life in the Ancient Seas. Since there is now an extensive whale evolution exhibit in Ocean Hall, this subject will not be a major part of the new paleontology exhibit. Both Zygorhiza and the dolphin Eurhinodelphis will have to go.

After the old fossil halls closed, Smithsonian affiliate Mark Uhen managed to acquire the retired Zygorhiza mount for George Mason University, where he is a professor. The whale is now on display in the Exploratory Hall atrium, suspended 30 feet in the air.

Tapirs, Horses, and Oreodonts

The last two major renovations of the NMNH fossil exhibits occurred when mammal specialists were in charge of the Paleobiology Department, and as a result the halls ended up with a lot of Cenozoic mammal mounts (at least 50, by my count). Virtually every major group was covered, often several times over. This menagerie has been culled for the new hall, which will focus on specimens that best tell the story of Earth’s changing climate during the past 66 million years. Casualties include the trio of Hagerman’s horses, the smaller horse Orohippus, the tapirs Hyrachyus and Helaletes, the ruminant Hypertragulus, and the oreodont Merycoidodon. Interestingly, the classic hall’s three large rhinos are sticking around, and will in fact be joined by at least one more.

Brachyceratops (USNM 7953)

The pocket-sized ceratopsian historically called Brachyceratops has been on display at NMNH since 1922. Discovered in 1913 by Curator of Fossil Reptiles Charles Gilmore, this animal is one of only a few dinosaur species excavated, prepared, described, and exhibited entirely in-house at NMNH. Assembled by Norman Boss, the mount is actually a composite of five individuals Gilmore found together in northeast Montana.

Gilmore described Brachyceratops as an unusually small but full-grown ceratopsian, but in 1997 Scott Sampson and colleagues confirmed that all five specimens were juveniles. Unfortunately, the fossils lack many diagnostic features that could link them to an adult form. According to Andrew McDonald, the most likely candidate is Rubeosaurus. Nevertheless, without the ability to recognize other growth stages of the same species, the name Brachyceratops is unusable and is generally regarded as a nomen dubium.

It is not difficult to surmise why the Brachyceratops would end up near the bottom of the list of specimens for the new exhibit. It is not especially large or impressive, it doesn’t have a recognizable name (or any proper name at all, really) and it doesn’t tell a critical story about evolution or deep time. With limited space available and new specimens being prepped for display, little Brachyceratops will have to go.

Corythosaurus (USNM V 15493)

In 1910, Barnum Brown of the American Museum of Natural History launched the first of several expeditions to the Red Deer River region of Alberta. Seeing Brown’s success and under pressure to prevent the Americans from hauling away so much of their natural heritage, the Canadian Geological Survey assembled their own team of fossil collectors in 1912. This group was headed by independent fossil hunter Charles Sternberg, who was accompanied by his sons George, Levi, and Charles Jr. Having secured several articulated and nearly complete dinosaur skeletons, Brown’s team moved on five years later. The Sternbergs, however, remained at the Red Deer River, and continued to collect specimens for the Royal Ontario Museum.

In 1933, Levi discovered a well-preserved back end of a Corythosaurus, complete with impressions of its pebbly skin. The Smithsonian purchased this specimen in 1937 for use at the Texas Centennial Exposition. It eventually found its way into the permanent paleontology exhibit at NMNH. Unfortunately, the half-Corythosaurus ended up crowded behind more eye-catching displays and was often overlooked by visitors. In the new exhibit, it will have to move aside to make room for new Cretaceous dinosaurs.

Assorted Dinosaur Skulls

Original skull of Hatcher the Triceratops, one of many dinosaur skulls coming off exhibit. Photo by the author.

In addition to complete dinosaur mounts, the old NMNH fossil halls included several dinosaur skulls, ranging from the giant cast of the AMNH Tyrannosaurus to the miniscule Bagaceratops. Most of these standalone skulls have been cut, although a few (Diplodocus, Camarasaurus, and Centrosaurus) are sticking around, to say nothing of new specimens being added. Other retirees in this category include the original skulls of Nedoceratops (labeled Diceratops), Triceratops, Edmontosaurus, and Corythosaurus, as well as casts of Protoceratops, Pachycephalosaurus, Stegoceras, Psittacosaurus, and Prenocephalae.

As usual, the reasons these specimens are coming off exhibit are varied. The Nedoceratops skull is a one-of-a-kind holotype that has been the subject of a great deal of conflicting research over its identity and relevance to Maastrichtian ceratopsian diversity. Putting this specimen back in the hands of scientists should help clarify what this bizarre creature actually is. Meanwhile, many of the other skulls (e.g. Protoceratops, Psittacosaurus, and Prenocephalae) come from Asian taxa. In the new fossil hall, the Mesozoic displays will primarily focus on a few well-known ecosystems in North America.

Dolichorynchops (USNM PAL 419645)

The NMNH Dolichorhynchops is a relatively new mount. It was collected in Montana in 1977 and acquired in a trade with the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Arnie Lewis prepared it for display in 1987. 24 years later, “Dolly” is being retired to the collections. This is not due to anything wrong with the specimen, but to make way for a bigger, cooler short-necked plesiosaur. NMNH purchased a cast of Rhomaleosaurus from the Henry Ward Natural Science Establishment in the 1890s, but it has not been on exhibit since at least 1910. This cast, which is based on an original at the National Museum of Ireland (and which is identical to the cast at the London Natural History Museum) will make its first public appearance in over a century in the new National Fossil Hall. Sorry, Dolichorhynchops.

This has hardly been a comprehensive list – just a few examples that illustrate the decisions that are made when planning a large-scale exhibit. If you are curious about other favorites from the old halls, you can check on their fate by searching the Department of Paleobiology’s online database. Just go to Search by Field and enter “Deep Time” under Collection Name to see most of the specimens earmarked for the new exhibit.

References

Gidley, J.W. 1925. Fossil Proboscidea and Edentata of the San Pedro Valley, Arizona. Shorter Contributions to General Geology (USGS). Professional Paper 140-B, pp. 83-95.

Gilmore, C.W. 1922. The Smallest Known Horned Dinosaur, Brachyceratops. Proceedings of the US National Museum 63:2424.

Gilmore, C.W. 1941. A History of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology in the United States National Museum. Proceedings of the United States National Museum Vol. 90.

Gilmore, C.W. 1946. Notes on Recently Mounted Reptile Fossil Skeletons in the United States National Museum. Proceedings of the United States National Museum Vol. 96 No. 3196.

McDonald, A.T. 2011. A Subadult Specimen of Rubeosaurus ovatus(Dinosauria: Ceratopsidae), with Observations on other Ceratopsids from the Two Medicine Formation. PLoS ONE 6:8.

Sampson, S.D., Ryan, M.J. and Tanke, D.H. 1997. Craniofacial Ontogeny in Centrosaurine Dinosaurs: Taxonomic and Behavioral Implications. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 12:1:293-337.