Click here to start the NMNH series from the beginning.

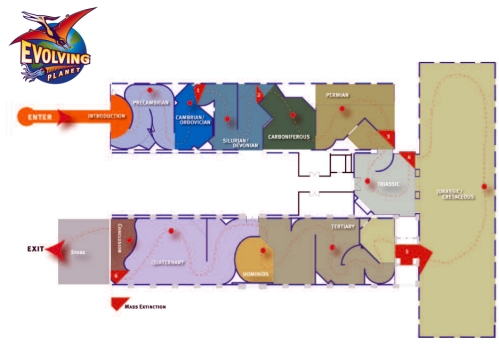

In the middle decades of the 20th century, museum theory and paleontological science were undergoing complementary revolutions. Museum workers shrugged off their “cabinet of curiosity” roots and embraced visitor-centric, education-oriented exhibits. Designers began to envision the routes visitors would travel through an exhibit space, and consider how objects on display could contribute to holistic stories. Meanwhile, paleontologists like Stephen J. Gould and David Raup moved their field away from purely descriptive natural history, exploring instead how the fossil record could inform our understanding of evolution and ecology. The common thread between both transitions was a focus on connections – bringing new meaning and relevance to disparate parts by placing them in a common narrative.

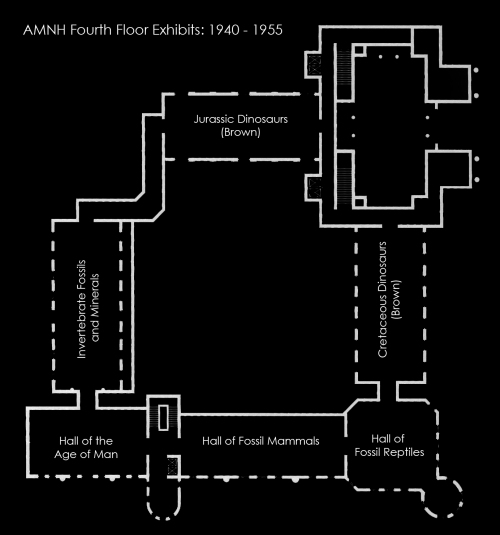

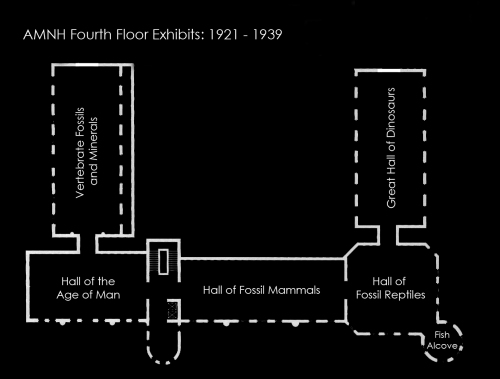

Between 1953 and 1963, the Smithsonian implemented an institution-wide modernization program, transforming virtually every exhibit in the museum complex. The National Museum of Natural History began renovations to its classic fossil halls in 1959, and the new exhibits were emblematic of contemporary trends in both museum design and paleontology. The plan, as devised by exhibit designer Ann Karras, was to do away with the loose arrangement of specimens and turn the east wing into a guided narrative of the biological and geological history of Earth. Responsibility for selecting specimens and writing label copy in each of the four halls fell to a different curator. In Hall 2, which housed dinosaurs and fossil reptiles, that curator was Nicholas Hotton.

Hotton joined NMNH in 1959 as an Associate Curator of Paleontology. Entirely onboard with Karras’s vision and the paleobiology movement as a whole, Hotton described the old exhibits as “crowded” and “unorganized.” He thought NMNH had plenty of dinosaurs, but “mammal-like reptiles”* were sorely needed if Hall 2 was to tell the complete story of amniote evolution. Following that, Hotton’s mission over the next several years was to assemble a respectable collection of synapsid specimens for NMNH, and to incorporate them into a well-illustrated exhibit on the origins of mammals. This post highlights just a few of the specimens featured in Hotton’s version of Hall 2.

*In Hotton’s day, early mammalian relatives were usually called “mammal-like reptiles”, hence their inclusion in the fossil reptile exhibit. Today, most specialists prefer a more precise definition of reptiles that excludes synapsid (mammal-line) animals. In this post, I will be using the modern classification wherever possible.

The Dimetrodon

Prior to 1960, the non-mammalian synapsid collections at NMNH were mostly limited to early Permian pelycosaurs. The most impressive of these was a Dimetrodon gigas collected in 1917 by independent fossil hunter Charles Sternberg. One of the best collectors of his day, Sternberg worked intermittently for E.D. Cope, O.C. Marsh, and various North American museums. In the summer of 1917, however, Sternberg was on a personal collecting trip with his son Levi. Their target was the Craddock Ranch bone bed of Baylor County, Texas, which was first explored in 1909 by a University of Chicago team. Sternberg was already quite familiar with this part of western Texas, having made some of the first thorough surveys of the Permian “red beds” in the 1880s, but the site itself was new to him. Nevertheless, Sternberg was extraordinarily successful that summer, collecting hundreds of fossils from a wide range of animals. He offered this bounty to the Smithsonian, and they purchased it from him immediately.

The Craddock Ranch fossils were particularly appealing because of their unique preservation. Buried in soft clay at the bottom of a shallow pond, the fossils could be removed from the ground with relative ease, and were largely free of encrusting matrix. Although few of the bones were articulated, many were identifiable. All told, the Sternberg collection included at least 35 skulls and partial skeletons from amphibians like Cardiocephalus, Diplocaulus, and Seymouria, plus hundreds of individual Dimetrodon bones, and a single articulated Dimetrodon specimen.

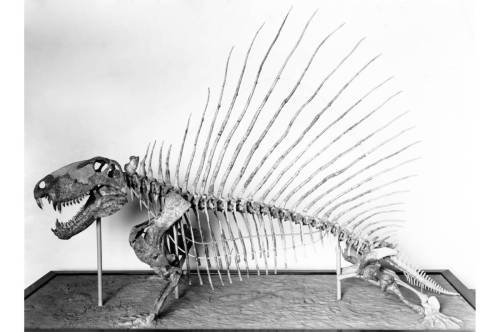

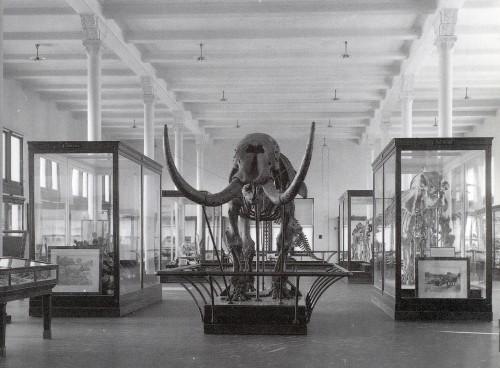

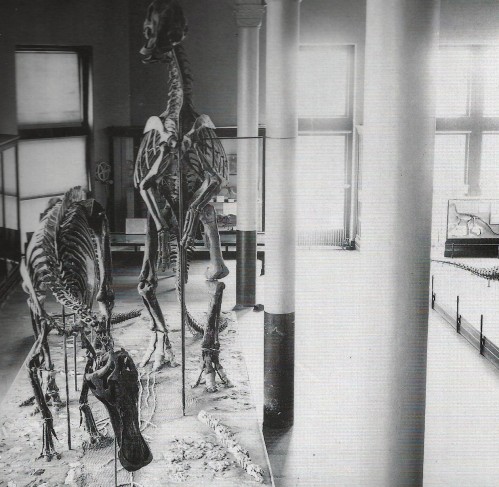

The Dimetrodon was first displayed on the north wall of the Hall of Extinct Monsters. Source

That Dimetrodon (USNM 8635) was the basis for a mount constructed by T.J. Horne. The articulated skeleton included a complete series of presacral vertebrae, the shoulder girdles, most of the forelimbs, and the left femur and tibia. The skull and jaw bones were found disarticulated, but bound together in the same mass of matrix as the skeleton. Horne added the pelvic bones and sacrum from smaller Dimetrodon specimens, and sculpted the rest of the missing material in plaster to complete the mount. Notably, his reconstructed tail was extremely short and stubby. Although the American Museum and Field Museum already had Dimetrodon mounts on display, the NMNH version stood out because of its open jaws, which Charles Gilmore said “gives the animal an appearance of angrily defying one who has suddenly blocked his path.”

Gilmore added the Dimetrodon to the Hall of Extinct Monsters in 1918. Like the other standing mounts constructed under Gilmore’s supervision, the skeleton was placed on a base textured and painted to resemble the rocks in which it was found. At this point in time, the NMNH fossil halls lacked any overarching organizational scheme, and interpretive content was minimal. Nevertheless, Gilmore displayed the Dimetrodon mount with both a small model and a 15-foot oil painting by Garnet Jex, which provided general audiences a better understanding of the animal’s life appearance.

Dimetrodon in the 1963 fossil reptiles exhibit. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

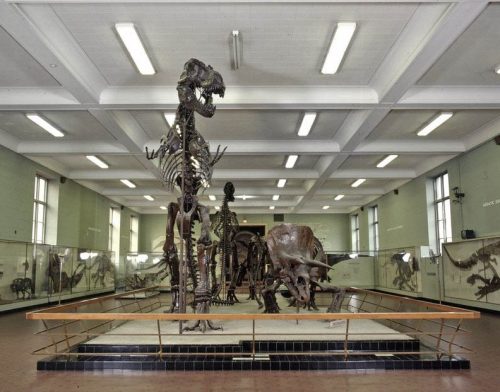

During the 1962 renovation, Hotton re-contextualized the classic Dimetrodon mount as a mammal ancestor. Unmissable orange arrows pointed to the specific anatomical traits that signify the animal’s kinship with mammals, including heterodont teeth and a single temporal fenestra. By design, visitors would pass Dimetrodon before visiting the true mammals in the adjacent hall.

The Dimetrodon skeleton itself was altered during the next renovation in 1981, when it was placed on a new, untextured base and given a longer replica tail. Contemporary staff also repainted the plaster sections to more closely resemble the original fossils – a surprising reversal of Gilmore and Horne’s original intention to make the reconstructed bones obvious to viewers.

The Thrinaxodon

Pelycosaurs like Dimetrodon represent the first major synapsid radiation, but by the middle Permian they were almost entirely replaced by therapsids. A more derived group which includes modern mammals, therapsids spread across the globe and became increasingly diverse as the Permian progressed. From weasel-sized burrowers to multi-ton herbivores, non-mammalian therapsids were among the first animal groups to conquer a wide range of terrestrial niches. Hotton wanted to tell this story in the modernized fossil exhibit, but there were hardly any non-mammalian therapsids in the NMNH collections. To correct this problem, Hotton took to the field for several months in 1960, and again in 1961. He joined James Kitching in exploring the Beafort Group rocks of South Africa, which were known to produce plentiful Permian and Triassic vertebrate fossils. Hotton returned to the museum with over 200 new specimens, the best of which were used in the renovated exhibit.

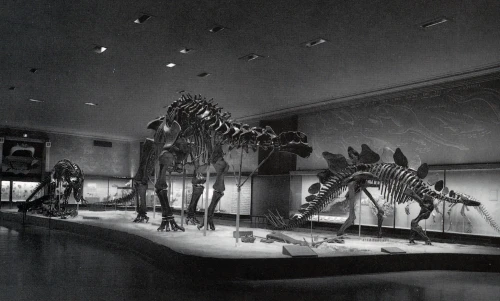

Hotton’s display of South African synapsids and amphibians. Note “Baby Doll” on the far left. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Hotton’s most prized find from South Africa was a gorgeously preserved and nearly complete Thrinaxodon liorhinus (USNM 22812). Hotton called this specimen “Baby Doll”, and while it was not prepared in time for Hall 2’s 1963 opening, it would later earn a spot of honor in the exhibit. Before that happened, though, Baby Doll was actually stolen by an over-enthusiastic volunteer. The FBI located and returned the fossil a year and a half later.

Since the 1980s, the Thrinaxodon has been displayed alongside the skull of Cynognathus crateronotus (USNM 22813), which Hotton collected on the same expedition. Both are members of the cynodont clade, which includes some of the closest relatives of modern mammals.

The Daptocephalus

Less than a month after hall 2 reopened, Nicholas Hotton returned to South Africa. This time, he was accompanied by his spouse Ruth Hotton and their three young children. For seven months, the Hottons traveled among fossil sites on different ranches, camping most nights. They collected some 300 specimens for the Smithsonian, and Hotton’s biostratigraphic mapping of the Beaufort Group brought a measure of clarity to this region’s historically convoluted geology.

Ruth Hotton made one of the trip’s most impressive finds while prospecting in a dry riverbed with her daughter, Carol (who is now a paleobotanist at NMNH). Turning a corner, she stumbled upon a dicynodont skeleton, completely exposed and lying in the middle of the channel. One can only imagine the surprise and delight of finding an articulated fossil skeleton completely uncovered. If the Hottons had been there one season earlier or one season later, the river would have undoubtedly destroyed the fossils.

Back at the museum, Nicholas Hotton prepared the specimen (USNM 299746) and determined it to be Daplocephalus leoniceps, one of the plethora of dicynodonts known from the Beaufort Group. Based on this classification, he reconstructed the damaged skull to resemble more complete Daplocephalus specimens, and added casts of Daplocephalus limbs.

As it turns out, however, USNM 299749 is not a Daplocephalus—it is a somewhat distantly related dicynodont currently called Platypodosaurus. To varying degrees, fossil mounts are hypotheses made of bone and plaster. They are based on the best information available at the time, but sometimes they need to be corrected. The NMNH “Daplocephalus” had been mislabeled and erroneously reconstructed for many years, but the 2014 renovation of the NMNH fossil halls now presented an opportunity to deconstruct the specimen and study it up close. As of 2019, Platypodosaurus was back on display with a newly reconstructed skull and limbs.

Thanks to Christian Kammerer for kindly sharing images and insight on “Daptocephalus”!

References

Gilmore, C.W. (1919). A Mounted Skeleton of Dimetrodon gigas in the United States National Museum, with Notes on the Skeletal Anatomy. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 56:2300:525-539.

Kammerer, C. (2015). Personal communication.

Lay, M. (2013). Major Activities of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology During the 1960s. http://paleobiology.si.edu/history/lay1960s.html

Marsh, D.E. (2014). From Extinct Monsters to Deep Time: An ethnography of fossil exhibits production at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. http://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/50177

Sepkoski, D. (2012). Rereading the Fossil record: The Growth of Paleobiology as an Evolutionary Discipline. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.